STRANGE DAYS Couldn’t Predict the Future Of Entertainment, But It Did Predict Everything Else

CINEMATIC DYSTOPIA is a look at the most prescient, most thoughtful, and most sobering films about societies gone mad, brought to you by writer and humorist Dave Schilling. Every week, he’ll examine movies not about the end of the world, but the worlds that carry on after everything’s gone to shit. You know, like right now.

The videos are hard to miss. Shaky camera-phone footage of police brutality, the contorted visage of white rage in the face of black people daring to live, a cop car barreling through a street protest, cities on fire. It’s shocking to realize how mundane it’s all become. It’s here, on-demand, whether you like it or not. Every day on social media is a one-stop horror show of the depths of man’s inhumanity to man. The only thing STRANGE DAYS got wrong about the future is thinking people would have to pay for it.

Kathryn Bigelow’s 1995 treatise on life in a post-Rodney King Los Angeles begins viscerally — with static, the electronic jolt of booting up, and a B&E gone wrong. Masked men storm a restaurant, hoping for a quick payday, but the police are on the way. Their frantic escape attempt ends with a splat, as the person whose perspective we’ve been seeing this whole time falls to his death. The simulation is complete.

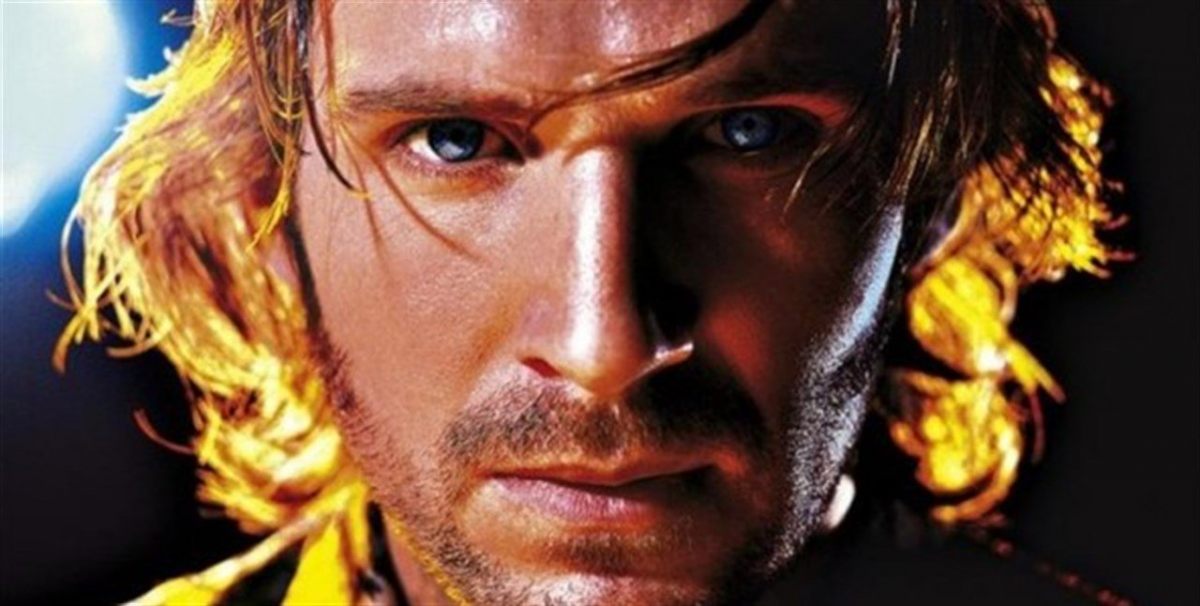

Lenny Nero (Ralph Fiennes) doesn’t deal in “blackjack clips,” though. For the screenwriters out there, this is the “save the cat” moment for Lenny, who is otherwise an unrepentant sleazeball ex-cop. He sells MiniDisc footage of people’s memories, recorded with the SQUID — a neural interface that reproduces sensations and images into first-person video that was originally designed by the FBI to replace microphones and wiretaps. “At least he doesn’t sell snuff films,” we say.

Fiennes plays Lenny as someone who believes they’re more charismatic than they actually are, simply because they’ve been lucky enough to scrape by for this long. He’s ducking creditors, eating pizza in his car, and spending most of his nights pornographically watching SQUID clips of his long-since-ended relationship with Faith (Juliette Lewis). Faith is a red-flag waving would-be rock star trainwreck who left him for an even sleazier music promoter ('90s heel-du-jour Michael Wincott). Faith’s new boyfriend just so happens to manage Jeriko One (Glenn Plummer), the biggest hip-hop star in this alternate universe version of the year 1999 who has recently turned up dead under mysterious circumstances.

All of the racial unrest, income inequality, and militarization of the police force that troubled the nation in the mid-'90s has spiraled out of control by 1999. LA is now under martial law. Riots don’t just spring up, they seemingly never end. Jeriko One is the most prominent African-American cultural voice in this world. His music and rhetoric advocates armed resistance to an oppressive and racist system. Every black character in the film (and there aren’t that many, to be honest) speaks about him like he’s a prophet, a visionary, and a genius. As his death rocks the psyche of the nation, Lenny gets a clip he wasn’t expecting: the brutal murder and sexual assault of a sex worker that’s friends with Faith. Lenny enlists the only person he trusts to help him solve the murder: a chauffeur named Mace (Angela Bassett).

STRANGE DAYS was the brainchild of James Cameron. Yes, that James Cameron. In the late '80s, Cameron conceived of a film about the struggles against systemic oppression on the eve of the millennium. Instead of directing the script he co-wrote with Jay Cocks, he passed it on to Bigelow, his ex-wife who would go on to break barriers as the first and only woman to ever win a Best Director Oscar, for THE HURT LOCKER in 2010. Back then, Bigelow was mostly known for stylish action films about fragile masculinity like POINT BREAK and NEAR DARK. She was inspired to direct STRANGE DAYS after her experience assisting with the clean-up of LA following the Rodney King uprising. The violent aftermath of the King trial was not an isolated incident. It was the culmination of years of tension between LA’s police and their minority underclass.

The Vietnamization of the LAPD under Chief Daryl Gates had already been ongoing. In 1987, Gates initiated Operation Hammer, a series of deadly raids on private residences in South Los Angeles that disproportionately targeted African-American and Latino residents. In 2001, the LA Times looked back on the program and described a particular raid on 39th Street and Dalton Ave thusly: “Dozens of residents from the apartments and surrounding neighborhood were rounded up. Many were humiliated or beaten, but none was charged with a crime.” An officer who participated in the raid, Todd Parrick, is quoted in that same article saying “We weren’t just searching for drugs. We were delivering a message that there was a price to pay for selling drugs and being a gang member. With that mentality, 39th and Dalton was born. I looked at it as something of a Normandy Beach, a D-day.”

Being in LA at that time meant such things were always in the background, if distant for anyone lucky enough to make a living in the entertainment industry. STRANGE DAYS reflects that curious observer’s mentality, basing a grim thriller on an extrapolation of societal ills that the filmmakers never experienced first-hand. A much-discussed feature of life in Los Angeles is how one can cordon themselves off from the unpleasantness if they have the resources. There was no uprising over the Rodney King verdict in Beverly Hills, but in the scenario created by STRANGE DAYS, even the rich have to hire drivers who know martial arts and drive around in bulletproof limos. The truth about the 21st century is very different from what this film predicted. It’s actually easier for the wealthy to hide than ever before.

Through Lenny and Mace’s investigative efforts, we find out Jeriko One was murdered by two rogue LAPD officers during a traffic stop. If the tape gets out, it could lead to full-scale urban warfare. One of the more unintentionally funny elements of STRANGE DAYS is that LA is in such bad shape at the start of the film that it’s hard for the viewer to imagine it getting much worse, but all the characters seem to think it can. Lenny’s grand plan is to get the tape to the Chief of Police, whom he believes to be the benevolent opposite of the real-life Daryl Gates, during a New Year’s Eve celebration at the futuristic-looking Westin Bonaventure Hotel in Downtown LA. The Bonaventure also shows up in a film Cameron directed, TRUE LIES, which came out a year before STRANGE DAYS. The architecture is sleek, but oppressive. You can’t really walk the cordoned off sidewalks around it thanks to its proximity to traffic. Its layout of lounges, stores, sky-bridges, and inward-facing rooms is designed so guests never have to interact with the outside world. Architecture made so people could hide was common in the era, as chronicled in Mike Davis’s seminal book on Los Angeles as a real-world dystopia, City of Quartz. That it plays such an outsize role in the climax of STRANGE DAYS is surely no accident.

At first glance, such things make STRANGE DAYS read as heady, intellectual, and virulently political. In many ways, it is. This is a Hollywood blockbuster about police brutality with the director of TERMINATOR 2's name slapped on the script. There’s a transgressive quality to it just from that simple fact. It’s a hard-looking film, full of aggressive music, quick cuts, and actors in bad wigs. There’s a level of violence against women that is uncompromising, brutal, and borderline unwatchable, even when factoring in that this came from a female director known for thoughtful meditations on gender. On the other hand, this is still a Hollywood movie. Lenny’s gambit pays off. The police chief has the evil cops arrested. Justice is served, albeit on a small scale. Tom Sizemore’s loathsome rapist villain, Max, scoffs at the idea of a police conspiracy during his requisite bad guy speech at the end. STRANGE DAYS might be the ultimate “bad apple” cop movie. It posits that by working within the system, the system can be fixed. In essence, it says the system is good and that Jeriko One was wrong.

That’s where a flawed, yet fascinating movie where Angela Bassett gets to play superhero spins out of control. Jeriko One is an abstraction invented by white filmmakers to stand in for real-life figures like Tupac Shakur, NWA, or Ice-T; men who became massive artistic and cultural figures by writing songs about racism within the law enforcement superstructure. It seems like very little thought was paid to how Jeriko One would look, what he’d say, and how his music would sound. To be blunt, everything about this character is a failure. The brief snippet of one of his tracks that we hear is like listening to a child’s nursery rhyme about slavery rather than the work of an alleged genius. Instead of the Raiders snapbacks, Locs, and Dickies of the culture at the time, he dresses like a member of Digital Underground. Every other black person seems like they’d rather listen to Living Colour than “Straight Outta Compton.” The unintended consequences of the climax render Jeriko One’s rhetoric either irrelevant or misguided. Glenn Plumber does his best to bring a caricature to life in his fleeting screentime, but what’s on the page simply doesn’t work.

This is a recurring problem in dystopian cinema, one that started with early works like METROPOLIS and persists to this day. The auteurs of the genre often get overwhelmed by the technology, the whimsy, and the opportunity for grandiose setpieces and miss the humanity and the reality of the characters forced to live in Hell. BLADE RUNNER, which is a clear influence on STRANGE DAYS that we will get to in this column soon enough, is not a movie about humanity in a dystopia. It’s about robots, identity, and dehumanization. That’s not intended to be a criticism of what is arguably the finest live-action work of the genre. It’s a beautiful, brilliant movie, but it’s an admitted intellectual exercise. Jean-Luc Godard’s ALPHAVILLE, another movie we’ll discuss here, is similarly interested in philosophy over humanity. Movies like ROBOCOP and VIDEODROME (yup, we’ll get to them, too) are about technology and how it corrupts humanity, rather than the everyday lives of regular people. There are exceptions (BRAZIL and MODERN TIMES jump out immediately), but there’s often a fetishistic quality to movies like STRANGE DAYS.

Dystopian films are allegories and satires first and foremost. Jeriko One didn’t need to be more than an idea that sets our heroes off on their journey, but the filmmakers felt like the idea of the SQUID tech required far more attention: multiple scenes of exposition-heavy dialogue and the aforementioned thrilling cold open. The characters are all film noir archetypes, which allows the ideas to go down smoother. They try to get by on short-hand with the characters so the film can proceed with the action scenes and the musical performances where people in fetish gear watch Juliette Lewis warble a PJ Harvey song.

Don’t misunderstand me, though. The idea of the SQUID is a very worthy sci-fi concept. It presaged the compulsive voyeurism and schadenfreude that defines social media. Lenny’s sad-sack obsession with watching clips of Faith is instantly recognizable to anyone who stayed up past 2 AM drunkenly flipping through Facebook or Instagram photos of an ex. As ideologically frustrating as the final act of STRANGE DAYS can be, the hope it provides has some basis in our reality. An argument could be made that the 1991 videotape of Rodney King’s beating, and today’s proliferation of cell phone footage of the murders of people like George Floyd, are a net positive for society because they force us to confront our lesser nature, like Lenny is forced to endure the blackjack clip that sets the plot in motion. The men and women who do evil and perpetuate racism can’t hide from the truth of the camera anymore than the LAPD officers of STRANGE DAYS could suppress the SQUID clips of them executing Jeriko One. But Rodney King happened in 1991. STRANGE DAYS was set in 1999. Now, it’s 2020 and the same problems exist, modern wonders of science be damned. The camera allows people to feel cathartic, righteous anger for a few days — like the SQUID, providing a safe distance from horror — but the virus of hate persists unchecked.

By emphasizing the technology and racing to its upbeat climax, STRANGE DAYS fails to capture the totality of the moment in which it was made. Its final shot of idealized racial harmony — biracial couple Lenny and Mace romantically embracing amongst a multi-ethnic, horny mass of partygoers literally rolling on ecstasy — says there’s a path forward, that equal coexistence is possible if we all could see the truth on the videotape. It assumes, like most mainstream Hollywood science-fiction stories, that we are all inherently good people corrupted by those few “bad apples.” The actual truth on the videotape, the footage we see every day of average citizens like Amy Cooper, says otherwise. It says that maybe we’re inexorably tied to our hatred, that we can’t transcend it, and that the best we can hope for is simply to admit it.

Every week, we’ll wrap this thing up with my version of online neighborhood rankings, but for the miserable cityscapes imagined in dystopian cinema. These rankings are out of 10, with one being a horrendous nightmare and 10 being STAR TREK: THE NEXT GENERATION.

Los Angeles in Strange Days:

Walkability: 1 — Maybe get a cab, preferably a bulletproof one

Good for Families: 1 — Mace has a kid, but does he look happy? No.

Arts and Culture: 4 — A quick browse of the STRANGE DAYS soundtrack says most music in this universe is people screaming about how life is pain. So, points if you are into that kind of thing.

Neighborly Spirit: 1 — Just a reminder: there’s a black market for videos of people committing violent crimes.

Best for: Biker gangs, Glenn Danzig

Next Week: JOSIE AND THE PUSSYCATS imagines an America where government-sponsored mind-control is commonplace, pop stars are murdered to stay silent, and Rachael Leigh Cook is the biggest star on the planet.