The Devin’s Advocate: The Rules For Found Footage Films

It doesn’t seem like found footage films are going away. I doubt they’ll be the stuff of serious mainstream films - ie, there will probably never be a found footage reboot of Transformers - but what I thought was a gimmick that would fade is stubbornly sticking around. Apollo 18 opens this weekend, while Atrocious and Troll Hunter have both recently been in theaters. Paranormal Activity 3 is coming this October, there’s a sequel to The Last Exorcism in the cards, and there’s even a found footage TV series, The River, coming from Oren Peli (whose Area 51 found footage film remains lost in limbo).

Found footage films can be a boon to low budget filmmakers, but they can be a real headache for audiences - literally and figuratively. So assuming that found footage isn’t going to simply die off but will remain a viable subgenre (mostly of horror) for the next few years, I’ve come up with some rules.

1) Be relatable. The found footage style is all about first person involvement. The point of view of the characters is the point of view of the audience, and we should be relating to the situation, feeling as though we are there. While found footage films should eventually get beyond the relatable into the fantastic, they need to begin in a space we recognize. Which is what’s weird about Apollo 18, a movie that is set on the Moon, one of the least relatable landscapes imaginable. Paranormal Activity works because it’s in a house, Blair Witch Project works because it’s in the woods, Cloverfield works because it’s in a city. A found footage movie set in Atlantis or some other fantastical, non-relatable setting automatically punctures the suspension of disbelief the entire style needs.

2) Establish a reason to film. Maybe this should have been the first rule. I guess rules one and two form together to one mega-rule, which is simply: establish suspension of disbelief. The audience will immediately begin to question why the characters are filming things if you don’t establish strong reasons for them to be doing so. This rule basically applies to the conceptual aspect of the movie - ie, why are these kids in the woods filming themselves - and not to the specifics of scenes. If you’re doing it right audiences will be caught up enough in later scenes that they will forget to question the fact that filming is going on. That said, you should still try to establish, on a scene by scene basis, a good reason the characters are filming what is happening.

3) Cut to the chase. Boring the audience for 40 minutes is not building suspense. One of the worst sins found footage filmmakers commit is that they haven’t come up with enough story to fill a running time, and so the first half of the movie is excruciatingly boring scenes, often poorly improvised by amateur actors. This is where the hamfisted attempts to create characters and personal conflicts are done, and they’re usually insufferable. What’s worse is that this stuff doesn’t even work on a meta level - why would someone who was cutting together this ‘last known footage’ include 30 minutes of people randomly yapping in a car or on a trail? Some films get around this by pretending to present ALL the footage shot, but even that feels wrong and is too tedious.

While this style has the same general narrative needs as a traditional film, I believe the first act is the least important part of a found footage film. Further, a found footage film should be about as short as possible, so cutting out all of the strained banter in act one will only help make a stronger movie.

4) Embrace the limitations of the style. When you’re telling a story via found footage you’ve committed to telling a story with much less exposition than a normal narrative. Embrace that. This is where all of the screenwriting cliches really come alive - make sure that action is character. Unless you’ve established a GREAT reason for these people to be addressing the camera and giving their life stories, keep that information to yourself.

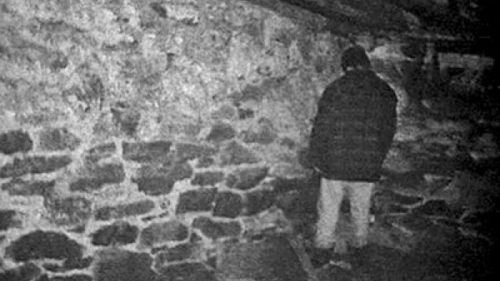

That’s important on a narrative side as well. Found footage films are the 21st century version of those HP Lovecraft and Edgar Allen Poe stories where the first person narrator is doomed and writing his last words. These stories continue to resonate because of the mystery around the edges, the limitations of the first person narrator. Embrace that as well! Do not bow to the need to explain everything or to show what, in a traditional narrative, would be the money shot. Remember that the money shot of The Blair Witch Project is a guy standing in a corner.

Remember: the single most disappointing part of any horror movie is the reveal of the monster. This format allows you to never reveal the monster and to continue to milk the suspense and fear of the unknown right up to the last frame.

5) Commit to the style. Too many found footage films decide, in the climactic moments, to not really be so much found footage anymore. Directors will throw in shots or angles that don’t really make sense in terms of the found footage conceit, will sometimes do cutaways that break suspension of disbelief or will otherwise just fudge the rules to get a good shock in there. Don’t do that. While the found footage style is technically cheap and easy, to be done right it requires the most thought and discipline. What drove me crazy about The Last Exorcism is that it becomes almost a straight narrative in its final minutes, with the camera getting every single shot as perfectly as possible.

Basically the audience has allowed you the conceit that this is a ‘real’ thing. Stick to that conceit right up to the end. The original Paranormal Activity didn’t even have end credits. It isn’t necessary to do a whole ‘this is real footage’ song and dance, but if you don’t cheat the audience will appreciate it. And going back to rule 4, you can use that commitment to make the film better and scarier.

These rules are mostly for found footage horror films; technically you could do a found footage movie in any genre (see De Palma’s Redacted), but I think these rules would still apply. And I’m sure any and every one of these rules, as any ‘rule’ about art, could be quite successfully broken. Hell, I’m hoping somebody makes an amazing Atlantean found footage film.