Framing CALIGARI: The Unplanned Birth Of Cinema’s First Unreliable Narrator

Movies have long thrived on the unreliable narrator. Yes, kids, even before Fight Club and The Usual Suspects. A protagonist who is lying to us, to other characters or to themselves is a great cinematic device, one that keeps us at arm’s length while simultaneously letting us into their heads. And while it might seem to be a distancing effect it often, ultimately, does the reverse: as human beings, we can’t help but see ourselves in the liars, the phonies and self-deluding protagonists onscreen.

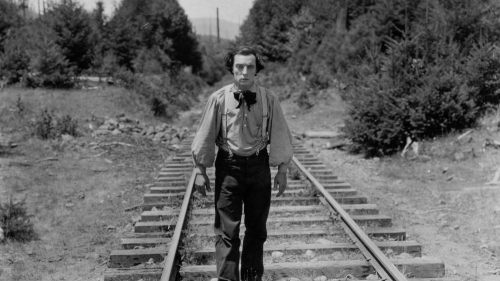

While the unreliable narrator goes back centuries in literature, most scholars agree its filmic debut was in 1920’s The Cabinet Of Dr. Caligari. Anyone with a passing interest in cinema knows the story, but for the rest of you: a young man (Friedrich Fehér) tells a stranger a story in which he encounters an evil carnival hypnotist (Werner Krauss). The hypnotist uses a murderous somnambulist named Cesare (Conrad Veidt) to wipe out his enemies. The young man’s love (Lil Dagover) is eventually menaced and kidnapped by Cesare, and in a climactic chase, the hypnotist is revealed to be living a double life, as the respected head of a nearby asylum. Confronted, he flies into a rage before he is subdued and committed to his own asylum. But in the film’s final minutes, it’s revealed to us that the young man’s story is a complete delusion, and he is himself an inmate in the doctor’s asylum, every other character in his story just another mad patient.

The film’s framing device and final twist were pretty innovative for 1920 - very probably the first instance of an unreliable narrator in cinema - and it echoes throughout the 95 years of cinema that followed, from The Wizard Of Oz to Spellbound to Shutter Island. The unreliable narrator has become such a staple of cinema that there’s a growing trend to cram it into films where it doesn’t exist, birthing more and more insipid “theories” about how this film was just a dream, that film didn’t happen. Just a few years after the Lumiere Brothers’ footage of a train rushing toward the camera sent audience members running for their lives, Caligari’s somewhat self-reflective idea that what you’re watching “didn’t really happen” captured audiences’ imaginations in a big way, and is still being used 95 years later.

And it was sort of unplanned.

There might not ever be a definitive account of exactly what happened, but according to some sources and interviews, the writers of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari - Carl Mayer and Hans Janowitz - never meant for their tale to be framed as a madman’s fantasy, and pitched a fit when it emerged as one. As originally conceived, Caligari was their anti-authoritarian screed, an Expressionist fable literally painted in broad, misshapen strokes, condemning the dehumanizing effect of “arbitrary authority” imposed on the individual. The writers poured their personal experiences into it - Mayer’s sessions with a military psychiatrist formed the basis for the film’s title character, while a visit to a fortune teller who accurately predicted his lover’s death informed the Cesare character. Janowitz’s wartime experiences left him mistrustful of authority, and he claimed to be haunted by a murder he witnessed at an amusement park.

One of the directors considered for the film was a young Fritz Lang, who allegedly suggested a framing device for the surreal tale. A bookend which incorporated a more naturalistic look and feel would present the main story as the skewed delusion of a fractured mind. Though Lang left the project early on, the idea remained, and (again, allegedly) the writers were never told of the change until the film was finished. They protested and threatened legal action, to no avail. The Cabinet Of Dr. Caligari became recognized as a milestone of cinema, partly due to its unique look and feel, but also due to its clever framing device and twist ending.

While it’s hard to argue the writers' assertion that the framing device changes the entire meaning of the story - the film goes from an anti-authoritarian parable to a film that depicts those opposing the status quo as dangerous and insane - it’s harder to deny the merits, or at least the impact, Lang's changes made. Without the added layer of the framing device, the film is simply a stylized art project, a stilted fable with a fairly simple anti-establishment subtext. Lang’s suggestion might have made the film politically less provocative, but ultimately the framing device is what makes the film an important artistic milestone, introducing an additional layer to narrative film that has endured for a century. Of course, it must also be noted that by framing Caligari as the delusions of a madman, the film’s uniquely Expressionist sets, acting and makeup become explained away, made literal. In that regard, the film must also be credited/blamed with sending us down a path of depressing, thudding literalism where all dots must be connected and everything has to fit, a world where logic mustn't just trump storytelling; it must supercede it. Maybe those wronged writers were onto something.

The HD print of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari on Fandor is absolutely stunning. If you have 76 minutes, it's a crucial piece of cinema, and it's very likely never looked as good as it does here.