Alligator Smile: Tobe Hooper’s EATEN ALIVE

Joe “The Alligator Man” Ball is a somewhat familiar figure in Texas folklore. Following service during WWI, Ball returned home to the US and became a bootlegger, running moonshine across state lines. Once Prohibition ended, he opened the Sociable Inn in Elmendorf, Texas – a saloon that came complete with its own alligator pit. The reptiles served as a drunken sideshow attraction, as Ball would charge customers a few pennies apiece to watch the animals eat. Adding a layer of hideousness to the already outlandish proceedings, the Inn’s owner would feed the scaly beasts live cats and dogs, the furry strays’ struggle transforming the trench into a redneck coliseum.

Women began to go missing in the area, and their bodies were traced back to Ball’s place of business. Turned out, the reptiles were getting a healthy dose of human flesh to go along with the alley cat hors-d'oeuvres. Misunderstanding the term “corpus delecti,” the Alligator Man believed that the lack of bodies meant he could never be convicted of the multiple murders he was committing. Once alerted that the authorities were on to his macabre misdeeds, Ball realized his capture was imminent. On September 24, 1938, Texas Rangers stopped into the Sociable Inn, looking to arrest the now notorious serial killer. Ball nonchalantly rang up a "No Sale" on the punch register, removed a pistol from the drawer and placed it in his mouth, blowing his brains all over the back wall. His handyman, Clifford Wheeler, was tried and convicted to jail time as an accessory, and the alligators were donated to the San Antonio zoo.

Being a good Texas boy (and obvious fan of disreputable mythology), Tobe Hooper collaborated with his Texas Chain Saw co-conspirator Kim Henkel and looked to Ball’s saga as inspiration for their 1977 follow-up, Eaten Alive. However, instead of sticking with the sunny nihilism of their stunning masterwork, Hooper and Henkel create a hothouse staginess that feels like a sordid mix of trash and high art. Imagine Tennessee Williams intending Cat on a Hot Tin Roof to involve backwoods prostitutes, a man-eating ‘gator and the yokels who fall prey to a madman’s scythe, and you’re certainly in the tonal ballpark. This is Brechtian horror of the acidic kind; drenched in a layer of sweat and hellish red light that causes the viewer to perspire along with the deviants who call this diseased universe home. It’s deeply unpleasant, but also unsubtle in its gallows humor and ability to allow the audience to chuckle along with these nitwit degenerates.

The debatable part is whether or not this lurid hyper-reality was entirely Hooper’s doing. Eaten Alive was a disgracefully difficult shoot; the first in a career trend that would culminate with (mostly confirmed) rumors of Steven Spielberg directing the majority of Poltergeist while Hooper attempted to kick a coke addiction. Filmed entirely in California sound studios (as opposed to the rugged, grime-smeared locations of Texas Chain Saw), Hooper reportedly handed over directing duties to DP Robert Caramico on several occasions. This white flag followed numerous disputes with Hooper’s producers, which may partially account for the utterly jaw-dropping tonal shifts.

Nevertheless, the performance direction sheds the naturalistic tone of Chain Saw, instead opting to predate the psychotronic histrionics that would define that movie’s first gonzo sequel. From Robert Englund’s lecherous entrance (“Name’s Buck, and I’m rarin’ to fuck…”) to Neville Brand’s mumbling embodiment of Texas legend, these characters could’ve only sprung from one twisted auteur’s brain. Outside of Leatherface, mentally disturbed Starlight Hotel manager Judd (Brand) may be the quintessential Hooper antagonist – waving his long blade around with the same pent up sexual frustration as his ladyflesh-masked cousin across the state.

Hooper reteams with Wayne Bell to deliver a sonic companion piece to the buzzing, industrial distortion that punctuated the director’s monumental moment in horror cinema. The score for Eaten Alive is perhaps the picture’s most discordant element, punctuating scenes with an assortment of atonal polluted noise. Only where Bell and Hooper’s musical textures often heightened the implication of the Sawyer Family’s ferocity, here it’s drizzled on top of copiously squirting karo syrup. Hooper struggled with obtaining a proper rating for his sophomore slasher, infamously landing on the UK “Video Nasty” list despite numerous cuts made by the censor board. It wouldn’t be until 2000 – twenty-three years after the picture’s initial release – that the film would be passed completely uncut by the BBFC. Though impossible to prove, it’s a safe bet that the score only made members of the board that much more uncomfortable when approaching the extreme violence in Eaten Alive; seasickness via sonic assault.

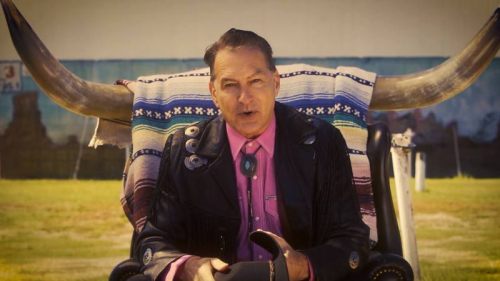

Everything about Eaten Alive is mean as hell, but in a much different manner than Texas Chain Saw. Where Chain Saw was fascinated with delving headfirst into an abyss of unknowable, merciless evil, Eaten Alive seems more content to poke the audience right in their bellies with the tip of its blade and then guffaw uncontrollably. From the moment Judd’s oversized prize devours a wayward family’s terrier (a mutt patriarch Bill Finley mimics in one of the movie’s more bizarrely theatrical moments), it’s clear that Hooper & Co. are having a laugh at everyone’s expense. To add insult to injury, the majority of the climax places a child (Kyle Richards) directly in harm’s way – breaking an age-old filmic taboo seemingly for shits and giggles. Eaten Alive mines the depths of Texas lore for its own perverted amusement, and ends up establishing a key element of Hooper’s filmography going forward. No longer was he going to be the stone-faced observer, keen to melt faces with scorching impeachments of innocence lost. Instead, he transmutes into a trailer park huckster, wiping the spittle from his beard and hoping that you lean a little too far over the railing while peering into his own personal alligator pit.

Eaten Alive is available now on a stunning Blu-ray/DVD dual format set from Arrow Home Video.