David Bowie’s Gift Of Sound + Vision

David Bowie was a huge part of my life growing up. I’ve gone into it on the site before, and earlier today Devin beautifully covered just how the Man Who Fell To Earth was a cosmic lifeline to misfit adolescent kids in the '70s and '80s. So I won’t get too autobiographical here. But it’s been amazing to read on social media feeds just how many different people - how many different kinds of people - regarded Bowie as not just significant, but as personally important to them. Bowie loomed large in our lives, he mattered to so many of us, and like it so often goes with these things, we maybe didn’t even realize it until he died. This otherworldly being whose many public personas were all about putting on a mask and keeping the world at arm’s length - somehow this week he made us all feel connected to one another. This news was so very terrible to wake up to, but seeing the reactions has been like finding out we were all in some secret club together without knowing it. Bowie changed my life; Bowie saved my life; Bowie was my life. You’ll hear variations on these sentiments all week. You can believe them.

There’ve been other reactions - young folks on Twitter and elsewhere are saying they never got into Bowie, that they didn’t realize Bowie meant so much to pop culture, that they didn’t realize “that’s where the lightning bolt on the face came from.” Ack. That rattles me to my core, but today is not the day to be cynical. There’s a generation who grew up without Bowie, and their world will be a little less magical than ours. You can sneer at them, or you can take pity on them and help them see what they missed.

I’ve no doubt there will be thousands of words spilled in the name of doing just that. The problem is that Bowie’s contributions are not something to simply discuss; they’re something to hear and, to a surprisingly equal degree, something to see. Certainly that’s apparent in his imagery, his many looks, his iconic album covers. But Bowie also capitalized on moving images like no musical act before him. He was perhaps our most cinematic pop star, embracing the visual side of rock-n-roll with as much fervor as the aural aspects. Elvis Presley made 31 movies, and the Beatles embraced the motion picture as an art form, but David Bowie is maybe the first pop star to engage the visual aspect of rock so fully that you almost can’t talk about his music without getting into the visuals he brought with it. And maybe in showing off some of his key audiovisual moments below (NOT a comprehensive list, by any means), the kids who are waking up late to this party can start to see what the fuss was all about. If you’re new to Bowie, I compiled this collection of clips specifically for YOU. If you’re engaged in the popular culture but are unaware of Bowie’s contributions to it, let this be a starting point toward fixing that. I promise it's worth it!

Bowie’s first real public splash came from his 1969 single “Space Oddity.” The singer probably knew he could make waves by releasing this single to coincide with the moon landing; the BBC refused to play it until the Apollo 11 astronauts returned to Earth safely. In any event, this clip shows that even by age 22, Bowie had a strong, cinematic sense of showmanship, probably gleaned/sharpened while studying pantomime under legendary performer Lindsay Kemp.

Two more albums followed, and in The Man Who Sold The World and Hunky Dory, Bowie’s sound mutated from a kind of hippie hangover into something more aggressive, sexual, and exciting. In many ways the David Bowie we’d talk about for the rest of the decade “arrived” with his appearance on The Old Grey Whistle Test, and the broadcast premiere of his Ziggy Stardust persona.

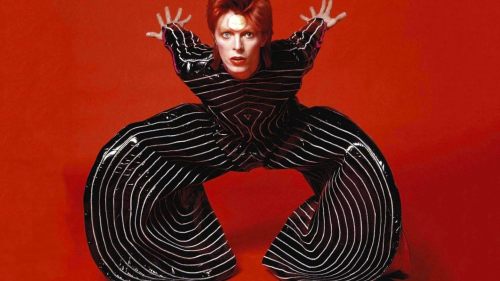

(For a sense of what this appearance did to the pop culture, stop reading here and go watch Todd Haynes’ hallucinatory, fictionalized account of the period, Velvet Goldmine.) From here Bowie took his relationship with the cathode ray tube into uncharted spaces. There was no MTV in 1972, but that didn’t stop him from collaborating with photographer Mick Rock on a handful of visually striking performance clips - “music videos” before the term existed - during which he pushed the Ziggy Stardust persona someplace even more otherworldly.

You can argue in the comments below who created glam rock, and to whom the biggest debt is owed for the genre, but Ziggy Stardust was the beautiful, gaunt, toothy face of the movement, no question. And he was no pre-fab construct hiding behind carefully produced films, either; Bowie/Ziggy was a reliably memorable live guest on shows like Top Of The Pops.

Others have written, are writing, and will write for years to come about how Ziggy Stardust landed on Earth and exploded pop’s preconceived notions of sexuality forever and ever (amen). True. But let’s take a minute to appreciate something else about this flashpoint. Less than two years after unleashing him, Bowie held a funeral for his glam alter ego via a 1973 concert film by DA Pennebaker. Opinions vary on 1973’s Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars, but not even chaotic, often blurry camerawork can diminish Bowie at the height of his glam-rock prowess, and the film captures the young star’s priority on reinvention as essentially the point of performance. Listen to that reaction when he announces he’s hanging it up:

He’s 26 in that clip. 26 and in complete control of his universe. For perspective, watch this interview clip from that same year. On stage, a master showman. Offstage, Bowie is as shy, reticent, awkward and nervous as you’d expect a 26 year-old to be.

It’s positively disarming. Consider also the courage of a 26 year-old, who’s been chasing success for a third of his life, jettisoning the winning formula a year after hitting it. Find me a 26 year-old today who would do that.

While plotting the next phase, Bowie’s released an album covering songs he liked as a teen. Pin-Ups was a quickie, released the same year as Aladdin Sane, and it’s better than a lot of '70s performers’ best work. Shades of Ziggy linger as Bowie says goodbye to the Starman, his own teen years, and the broad theatricality he picked up from Kemp.

That’s not to say he gave up theatrics; 1974’s Diamond Dogs is a concept album rising from the ashes of Bowie’s coke-fueled plans to turn George Orwell’s 1984 into a musical. Mrs. Orwell was a firm “no” on that one, so Bowie changed gears and created what might be his most sophisticated masterpiece. He launched an elaborate stage show to go with it, but allegedly abandoned the show’s expensive, unwieldy set pieces halfway through the tour. Parts of the show’s stripped-down version were folded into a documentary called Cracked Actor.

Next Bowie headed to Philly to record Young Americans, then to New Mexico to film Nicolas Roeg’s The Man Who Fell To Earth. Somewhere in there he created the sublime, six-track Station To Station, which (along with a growing drug habit) birthed his “Thin White Duke” persona. (Bowie seems less invested in creating visuals to go with the music during this period; tellingly, the cover art of both Station To Station and its follow-up recycle stills from Roeg’s film.)

Then Bowie went to Berlin where, aside from co-writing and producing two of Iggy Pop’s best albums, he cleaned up and collaborated with Brian Eno to create Low, “Heroes”, and Lodger. Perhaps some of the most “alien” music of his discography up to that point, the version of David Bowie presenting the music was strangely devoid of flamboyant clothing, hair dye, or excessive edit points. As the camera moved in on Bowie’s face here in 1977, to fans it must have been akin to seeing Lady Gaga or Marilyn Manson performing without makeup.

Of his three Berlin albums, 1979’s Lodger yielded the most in terms of music video performances, including a bizarre, legendary appearance on SNL featuring Bowie’s head green-screened onto a puppet that whipped out its penis. Lodger also gently shifted his “Berlin trilogy” away from the chilliness that had been creeping into his work, and back toward a more pop sensibility. His accompanying video efforts even toyed with Bowie’s androgynous past.

From 1980 forward Bowie would from time to time try to reconcile with his early success, with mixed results. We wouldn’t let him move past it - how could we, really? - but his attempts to put his past to rest were often as worthy as that past itself.

When MTV finally caught up with Bowie in 1983, his penchant for theatrics and showmanship was by now finely honed, and this synchronicity helped hurl Let’s Dance into the stratosphere.

Bowie would never top the commercial success of that 1983 album, but even if the music that followed wasn’t lighting the world on fire, the videos from that decade stood out - highly stylized, arch, weird little masterpieces that helped define the form.

Bowie kept moving forward in the '90s and '00s, turning out a lot of solid work that didn’t resonate with the public as largely as it should have. (If you’re digging in, Earthling and Hours are two personal favorites.) Without the kind of support he used to get from the media, his videos became less widely seen. But they weren’t any less interesting: this 2003 video (from the album Reality) showing the end of the world via a series of lenticular photographs is still pretty impressive.

Bowie going silent for a decade now seems extra tragic, but a heart operation in 2004 sidelined him, so much so that many of us thought he’d retired. When he re-emerged in 2013 with The Next Day, we got two new videos in quick succession; one sensed Bowie missed transmitting us pictures and playing with the form.

Likewise, we were treated to two videos from his final album Blackstar before the record was even out. David Bowie’s final video was released four days ago. Featuring the somewhat frail-looking star struggling to rise from a deathbed, employing the kinds of pantomime he learned in his teens, and hurrying to write down one last important journal entry, it’s both a broad caricature and maybe the most intensely autobiographical thing he’s ever done. What a perfectly Bowie thing to do.

Goodbye, David. For your gift of sound + vision, and for everything else, thank you.