Everybody’s Into Weirdness: SUSPIRIA (1977)

The Alamo Drafthouse is a brand built on weird. Beyond being situated in a town that has long aspired to remain eccentric in the face of all normality, it’s easy to forget that the original Alamo started as something of a private screening club, running prints of the odd and obscure into all hours of the night. Though the company has obviously grown into an internationally recognized chain of first run movie palaces, the Drafthouse Ritz in Austin, Texas remains committed to showcasing genre repertory programming, namely via its Terror Tuesday and Weird Wednesday showcases. This column is a concentrated effort to keep that spirit of strangeness alive, as programmers Joe A. Ziemba and Laird Jimenez (often pulling from the extensive AGFA archives) are truly doing Satan’s bidding by bringing ATX weekly doses of delightful trash art.

The thirty-third entry into this disreputable canon is Dario Argento’s psychadelic giallo classic, Suspiria…

Year: 1977

Trailer: Evil Laugh

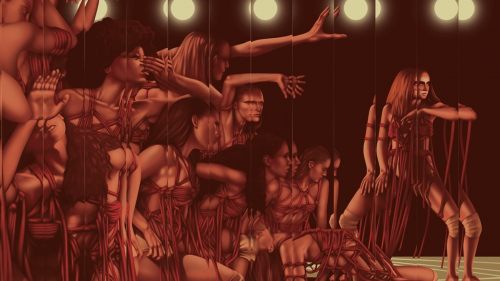

Suspiria isn’t simply one of the greatest horror films of all time, but rather one the greatest works of cinema, genre or otherwise, to ever grace the screen. Full stop; no exceptions, qualifications or caveats necessary. It’s a motion pictue that’s singular even within the distinct body of work writer/director Dario Argento had compiled up to that point in his career. No longer content to be the “Italian Hitchcock”, churning out potboilers fit for yellow-stained pulp pages, Argento bathes every frame in primary colors, immersing the audience in grandiose, grotesque psychedelia. We’re through the looking glass, praying to God we can somehow keep our soul intact as clawing, black-gloved hands pry at our soft, innocent figure. Once those sliding airport doors give way to driving rain and billowing winds, there’s no returning to reality. This is Argento’s version of a fairy tale, complete with unseen slashers and a bed full of razor wire.

Perhaps calling Suspiria a “fairy tale” is a tad misleading, as Argento is actually operating as a horrific Italian mirror to Walt Disney. Like Disney, the “Visconti of Violence” has almost zero need for filmic realism. Suspiria is stylized to the point of resembling animation; every color standing in for the emotions of its barely-sketched characters, acting as a kind of experiential decoder ring for the audience. Even the movie’s plot (as much as there is one) places a naïve “princess” – Suzy Banyon (Phantom of the Paradise’s Jessica Harper), a young American girl looking not too unlike Snow White – in an unknown, somewhat fantastical arena. But instead of a magical forest, Suzy arrives at a prestigious dance academy in Freiburg, Germany, only to find it doubles as a witches' coven. On top of having the girl battle supernatural forces, Argento fills Suzy’s dormitory with ballerinas, whose catty fierceness presents the sorceresses with some healthy competition. Should black magic not kill the girl, one of her hissing rivals surely will cause her to quit and fly back to Kansas.

Argento’s fascination with adornment and architecture heightens the “otherness” of the universe Suzy has entered. Each room of the academy is inexplicably ornate, plastered with decorations and wallpaper that create an inimitable artificiality. The irises near an instructor's desk allow your eye to drift over the scene as characters deliver awkwardly dubbed dialogue. The décor also often matches the aesthetics of the characters who call it home, as a flowery backdrop will accentuate one of the students’ flowing, flowery hair into infinity. The complex mise-en-scène adds an almost painterly texture to each of Argento’s frames, as every plane within a scene will be soaked in a different palette. Sometimes, this phoniness plays into the picture’s plot, as the “iris” reveals itself to be a trigger, allowing Suzy to navigate into the depths of the coven and discover the vast evil the academy’s facade hides. It’s this sense of purposefulness that keeps Suspiria from ever entering the territory of “stylistic exercise”, no matter how over the top Argento’s addiction to visual mischievousness becomes.

Nevertheless, no matter how striking Argento’s ghoulish fever dream becomes, Goblin’s soundtrack works to demolish the audience with its drifting, driving, demented tones. The prog band worked with Argento on a variety of essential soundtracks, cementing their legacy as a collection of cinema’s most idiosyncratic composers. Their contribution to George A. Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (which Argento helped birth) is sonically more varied, and their OST to the maestro’s best giallo, Deep Red, ultimately works better as a standalone record. Yet Goblin’s score for Suspiria is still one of the most unforgettable motion picture soundtracks of all time. Weaving together driving percussion, experimental noise, and ghostly, whispering vocals, it’s strikingly beautiful, often serving as a kind of language-free Greek chorus to the horrific happenings on screen. It’s a work that pushes Suspiria to a level of transcendent sensory overload that has rarely been matched.

The set piece has always been a defining element of Argento and the rest of his giallo comrades’ work, but Suspiria takes the movie’s illogical mindset and applies it to the gut-wrenching violence. Arms and hands appear out of nowhere to push a student’s face through a window, before pursuing her down a corridor and stabbing her through the heart (a puncture the director captures in woozy close-up). Another girl is chased into a hidden lair lined with barbed wire, in which she becomes tangled and writhes until she bleeds out. During the chaotic finale, dead ballerinas are resurrected in order to menace Suzy, bloody mouths wide and snarling as they raise sharp weapons above their heads, ready to deliver the deathblow. Argento’s embrace of surrealism renders these moments that much more frightening on a primal level. He’s tapping into the anti-reality of our worst night terrors, utilizing poor Suzy as a stand-in for our inability to outrun the seemingly omnipresent boogeyman. It isn’t until you catch your breath that you begin to realize how genius it all is.

Suspiria was initially conceived as the first chapter in a trilogy, based upon Thomas de Quincey's recounting of an opium dream about thee mothers: Mater Lachrymarum (Tears), Mater Suspiriorum (Sighs), and Mater Tenebrarum (Darkness). The movie’s first sequel, Inferno, comes close to recapturing the hallucinatory joys of its predecessor, but loses itself in underwater reveries and a complete disregard for conventional narrative. The less said about Mother of Tears (which came during the director’s dismal “late period”), the better, as it’s a sad reminder of how a prodigious artist can somehow misplace their once golden touch. Yet no amount of subsequent failures can lessen the impact of a true medium milestone. After nearly thirty years and (for this author) countless viewings, Suspiria remains a picture that never ceases to shock, amaze and astound. We often toss words like “masterpiece” around without a thought as to they actually mean, lessening their value. Suspiria is a true masterpiece – a movie whose texture and sonic intensity have never been duplicated, because they absolutely belong to its auteur.

This Week at Weird Wednesday: Shaolin Invincibles

Previous WW Features: Penitentiary; Skatetown USA; Blood Games; The Last Match; Invasion of the Bee Girls; Julie Darling; Shanty Tramp; Coffy; Lady Terminator; Day of the Dead; The Kentucky Fried Movie; Gone With the Pope; Fright Night; Aliens; Future-Kill; Ladies and Gentlemen…The Fabulous Stains; Pieces; Last House on the Left; Pink Flamingos; In the Mouth of Madness; Evilspeak; Deadly Friend; Don’t Look in the Basement; Vampyres; She; Dolls; Alice, Sweet Alice; Starship Troopers; Message From Space; Rabid; Child’s Play; Lost in the Desert