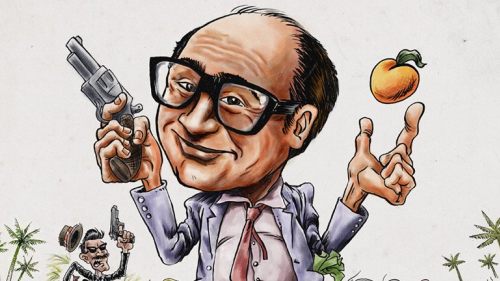

Todd Solondz Strikes Back in STORYTELLING

In honor of Wiener-Dog, which you can preorder here, we're taking some time to look back at the career of Todd Solondz.

They say don’t read the comments on the internet. You do it anyway. You just wanted to try to change a heart or a mind and instead, you’re at the bottom of a cartoon brawling fist and dust cloud, drowned out by a horde of dissenting opinions. As an artist, it’s generally the best practice to let your art speak for itself and not engage with the critics. But after Welcome To The Dollhouse and Happiness brought attacks at his propensity for exploitive characterization, Todd Solondz ignored that maxim. In Storytelling, the director opens up the proscenium arch to boldly monologue at every one of his detractors through various character sketches.

It’s a thrilling effort to watch a filmmaker so maligned leap fearlessly into a pit of his haters, throwing ‘bows with reckless abandon. On paper, going hard in the paint against your enemies seems like it would be a really cathartic experience. In some cases (say, Zack Snyder doubling down on his vision for Batman v Superman), it probably is. But Solondz, despite his brash storytelling style, isn’t aggro enough to sell petty vengeance as the main attraction in his work. He’s a little too sincere for that. Unlike the spiteful, stubborn Snyder, Solondz really gives a fuck. If anything, his vitriol indicates a deeper problem about his relationship with his critics.

Storytelling splits its running time between two unconnected narratives, each its own little short film. The first part, “Fiction”, follows Vi (Selma Blair), a college student in a creative writing class with her boyfriend Marcus (Leo Fitzpatrick), a manipulative asshole who happens to have cerebral palsy. The second (longer) section, “Non-Fiction”, stars Paul Giamatti as a Toby Oxman, a documentary filmmaker following a dysfunctional Jewish family in the suburbs, and Mark Webber as Scooby, the family’s eldest son who becomes the breakout figure in the film. There was a third portion called “Autobiography” that featured James van der Beek as a closeted football player, but it was cut before release.

There’s a reliably incisive tone on display here and it’s employed with such precision and dramaturgical economy as to be impressive. Unlike many indie auteurs, Solondz understands the importance of brevity and deploys his barbs with ruthless efficiency. The “Fiction” side of the film is chock full of pithy one liners fashioned out of expertly observed commentary, each dripping with more wit than the last. When Marcus reads his hilariously terrible short story to the class, leveraging his disability as a way to force the reader to sympathize with him, one of his dumbfounded classmates, at a loss for criticism, says “Updike has psoriasis.” It’s a bitter punchline executed with a master’s sense of timing. But there’s a brutality to his comedy and that’s what gets him in hot water.

In defense of his detractors, Solondz can be so singularly obsessed with envelope pushing agitprop that he begins to feel like an esoteric Facebook meme page, riddling equal opportunity targets with sarcastic darts. A surface reading of his filmography might call to mind the early seasons of South Park or the first few episodes of any prestige drama thumbing its nose at standards and practices. He wields a sharp tongue with his satire, lashing out with an assholish sense of glee. The way he forces viewers to come to grips with their natural revulsion to unsavory people and taboo subject matter can feel downright abusive at times. But that's a jaundiced, lazy reading of the stories he chooses to tell.

There’s a challenging sex scene between Vi and her black literature professor (Robert Wisdom) where he forces her to scream “fuck me, nigger” as he plows her from behind. It feels every inch as unsettling as anything Gaspar Noe has ever filmed, framed as it is with such a vanilla normalcy. It feels barbarous for no reason. When Vi writes about the experience, the class tears her story to shreds, calling it all sorts of racist and exploitive. One classmate asks “why do people have to be so ugly? Write about such ugly characters? It’s perverted.” Vi’s only method of defending herself is to exclaim that it really happened, which only leads her professor to vilify her, laying bare all the authorial subtext she left hiding in plain sight with exacting derision.

It’s clear here that Solondz is talking to his critics. Why does Solondz write about such ugly characters? Because the world he lives in is populated with ugly people. That cannot be denied. He argues that there’s no perversion in dramatizing the kind of fucked up things we witness every day and there’s no real malice to finding comfort in laughing at those horrors. In the “Non-Fiction” half, Oxman is a clear stand-in for Solondz as well. When Scooby’s little brother ends up in a coma after a football injury, his producer (Franka Potente) seems pleased at the development, as it will give his film the gravitas it needs, but Oxman sees the potential for comedy in the way the family reacts to the tragedy.

“What’s funny about a kid in a coma?” she asks. Nothing! There’s nothing inherently funny about a child teetering on the precipice of death. But it’s not the kid being in a coma that’s funny to Solondz. It’s the circumstances surrounding that particular trauma. There’s nothing naturally humorous about cerebral palsy, but a dickhead who is a shitty writer who happens to suffer from it writing the lines “no more cerebral palsy. From now on CP stands for cerebral person” is hilarious. He is also postulating that there’s nothing about how he tells a story that’s any worse than someone exploiting that kind of tragedy for dramatic purposes.

Critics have no qualms applauding bland, Oscarbait “explorations” of heady subject matter so long as they aren't too confrontational. It's all well and good to engage difficult topics if you keep the appropriate distance, offering viewers the opportunity to pat themselves on the back for watching something challenging without having to actually question themselves in the process. It's just more polite that way.

And that’s the joke at the heart of the film. It’s all exploitation. At least his is honest. The only thing holding Storytelling back, of course, is that he had to explain the joke to his critics in the first place.