Steve Ditko: The Father Of DOCTOR STRANGE

We are celebrating this week's Doctor Strange release (get your tickets here!) with a bunch of articles all dedicated to Marvel's Sorcerer Supreme.

We talk a lot about Stan Lee. You see him in cameos and on Entertainment Tonight and all those other Hollywood news for grammy and pawpaw shows. Ask your average Joe and he’ll tell you Stan Lee created all the Marvel characters like Spider-Man, Hulk, and even Captain America.

In truth, as you smarty pants readers know, Lee had nothing to do with the creation of Captain America, and he’s not the sole creator of any other character. Lee worked with a multitude of amazing creators who tend to be ignored when people talk about Marvel. Without these creators, we wouldn’t have the X-Men, Hulk or Doctor Strange.

With Doctor Strange coming to theaters, how about we look at little Stephen’s daddy, and the father of many other great characters, Steve Ditko.

On the second of November, in the year 1927, Steve Ditko took his first breath as a doctor slapped him on the ass. The second of four kids, Steve took after his father; both had a talent for carpentry and drawing, as well as a love for newspaper comic strips. Hal Foster’s Prince Valiant, with its beautifully detailed art, caught Steve’s eye at young age, but his obsession with comics didn’t really strike until he was dealt the one-two punch of Batman and The Spirit.

When he wasn’t reading Batman’s latest adventures in Detective Comics, Steve spent his high school years making wooden models of German airplanes to be used as reference by civilian aircraft spotters during World War II. Like many red blooded American men and women, teenager Steve wanted to do his part to stop those dirty Nazis and save the American way of life. Now, nothing in my research on Steve Ditko can point to exactly when he first read the work on Ayn Rand, whose books would help shape the artist’s political and personal beliefs, but I’m betting it was sometime during his high school years with the release of Rand’s first success, The Fountainhead.

Ditko enlisted in the army the moment he graduated high school, but arrived in Europe just after the war ended. Instead of fulfilling his goal of taking down a few Jerry’s himself, Ditko spend his time in the military drawing comics. After his time in the service was up, Ditko headed to New York and enrolled in the School of Visual Arts, which at the time had the less haughty name of the Cartoonists and Illustrators School. Ditko’s main goal at the Cartoonists and Illustrators School was to get into a class taught by Batman artist Jerry Robinson*.

Ditko’s work stood out to Robinson right away. Ditko didn’t just have a striking style in the same vein as Jack Kirby, his art allowed for more emotion to come through, especially in Ditko’s facial work. The young artist had a talent for displaying emotion that few others before or since could ever dream of pulling off.

It was in Robinson’s class that Steve Ditko would first meet Stan Lee. Robinson had invited Stan to speak to his class - Stan was an editor at Atlas Comics at the time - and Stan was impressed with Ditko’s work.

Apparently, Stan wasn’t impressed enough to give Ditko a job though. Instead, Ditko would start off working for second rate comic publishers (though to be fair, outside of DC/National pretty much every comic publisher was second rate in that post-war period) for books like Fantastic Fears and Daring Love. It wasn’t long before Ditko got a job working as a background inker for Jack Kirby and Joe Simon’s artist studio. Ditko mentored under Mort Meskin, whom he admired greatly. Before long, Ditko moved up from background inker to drawing his own comics, mostly for Charlton Comics, a third rate publisher better known for publishing lyric books at the time.

If this was a movie, we would be hitting the first big bit of drama right about here. Steve Ditko, young and successful, was struck with a nasty case of tuberculosis. Ditko, too sick to work, had to move back to his parent’s home in Jonestown Pennsylvania while he recuperated. If I’m wrong about Ditko getting into Ayn Rand and Objectivism while he was in high school, this period would be my second guess.

Ditko returned to New York in 1955 after spending a year at his parent’s home dealing with his illness. He quickly got work with Atlas Comics, working with Stan Lee as a fill-in team on a number of books, including Amazing Adventures. The Lee/Ditko stories proved to be popular with readers, leading to the duo fully taking over the book with issue seven, when the title was changed to Amazing Adult Fantasy to better reflect the types of stories Lee and Ditko were telling - human stories with a fantasy tint. Together, Lee and Ditko came up with what is now called the Marvel Method; Lee would give Ditko a short description of the plot of a story - sometimes as little as a single sentence - and Ditko would run with it, creating five to ten page stories. Once Ditko was done, Lee would come back and fill in the dialogue based on the art. To really pull off this kind of collaboration, you need serious talent on both ends, and these guys had it.

While they worked on Amazing Adult Fantasy, Atlas turned into Marvel. The “Marvel Age” began when Stan Lee and Jack Kirby introduced the us to The World’s Greatest Comic Magazine, Fantastic Four. With that, everything in the comics world changed.

Stan Lee, with other collaborators but mainly Jack Kirby, started a string of now classic books and heroes. It was with Stan’s best idea that he and Kirby ran into a problem. Stan came up with the idea of a teenaged hero called Spider-Man, but Kirby’s style didn’t work for it. Kirby designed a Spider-Man who looked kind of like Captain America but with a gun that shot out webs. It just wasn’t what Stan wanted, so Kirby’s six page story was tossed and Lee turned to Ditko. I think you know how that turned out…

Ditko would later claim that Spider-Man was mainly his creation. As he put it in an interview with Gary Martin published in Comic Fan, "Stan Lee thought the name up. I did costume, web gimmick on wrist and spider signal". Ditko handed on a story about a superhero that spent the first five pages in the home of an elderly couple raising a sickly, nerdy, teen boy. The image of Spider-Man in all his glory barely shows up in the story at all, but boy oh boy was it a hit with readers.

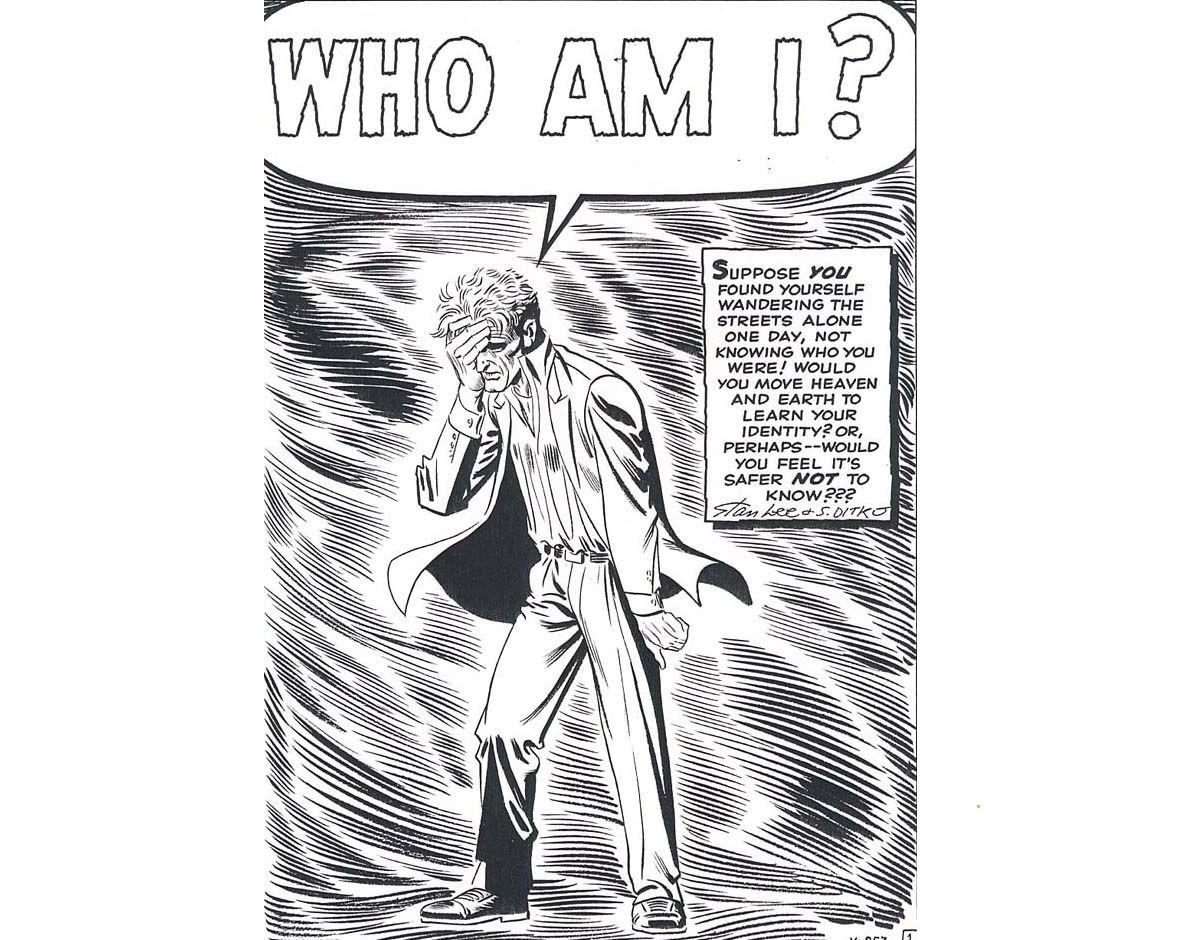

Ditko worked on a series of books at this time, including The Incredible Hulk. In something that seems unbelievable now, The Incredible Hulk was a bomb, and the series was cancelled with issue six. Finishing the issue, Ditko turned to creating a hero he wanted to see, a type of character he felt Marvel was missing - a magic based hero. Ditko went to Stan Lee with an already completed five-page story introducing his creation, for which he had yet to come up with a name. Lee decided to publish the story in Strange Tales, so they named him Doctor Strange.

Again, if this was a movie, we would call this the “good times montage”. Things were going well for “Sturdy” Steve Ditko, so you know bad stuff would follow. This time, that bad stuff came in the form of Ditko’s work not matching his beliefs.

By issue ten of The Amazing Spider-Man, Ditko was plotting and drawing the book; Stan Lee came in only at the end to fill in the dialogue. Lee wasn’t overly happy with where Ditko was taking the book - Ditko focused more on Peter Parker and less on Spider-Man. Issue eighteen barely had Peter doing any superheroics at all. Lee took a real cheap shot at Ditko in the columns of other Marvel books published that month, writing about the issue “A lot of readers are sure to hate it, so if you want to know what all the criticism is about, be sure to buy a copy.” This creative difference lead to constant arguments between the Lee and Ditko until they completely stopped speaking to each other around issue twenty-five.

Now, way way way back in issue fourteen of The Amazing Spider-Man, Lee and Ditko introduced a character that would become Spidey’s greatest foe, the Green Goblin. For nearly two years, the true identity of mean old GG remained a mystery. In issue thirty-seven, Lee and Ditko introduced a new character, Norman Osborn, the self-made millionaire father of Peter Parker’s buddy, Harry Osborn. Ditko wanted Norman to be a hero in the style of Ayn Rand’s books. I’ve personally never read Atlas Shrugged but smart peeps who have say Norman Osborn’s character in issues thirty-seven and thirty-eight is clearly a take on Hank Rearden. Ditko was starting to bring his Objectivism into his work, and he wanted Norman Osborn to become Peter Parker’s mentor, helping young Pete into the Objectivist life.

Stan Lee, on the other hand, had a different idea. For issue thirty-nine, he wanted to reveal that Norman was the Green Goblin. Instead of drawing that, Ditko quit not just The Amazing Spider-Man, but all of Marvel. Marvel fans were told of Ditko’s departure through the Bullpen Bulletins.

Ditko has never drawn Spider-Man again.

Steve Ditko’s story would pretty much follow this format for the rest of his career. He went back to Charlton Comics where he created The Question. He also did some work in two of the best horror comics ever published, Creepy and Eerie. Ditko even got to create his ultimate Objectivist hero, Mr. A. Most claim that Rorschach from Watchmen is based on The Question (and in truth, when Alan Moore first pitched Watchmen he wanted to use the Charlton characters, including The Question). In reality, Rorschach has more in common with Ditko’s Mr. A than with The Question.

Ditko ended up at DC Comics where he created the characters the Creeper and Hawk & Dove. Ditko’s tenure at DC would be short - he would quit six issues into Beware the Creeper due to continual disagreements with Hawk & Dove writer Steve Skeates, Beware the Creeper writer Denny O’Neil, and editor Dick Giordano, mainly on his wanting to bring in more Objectivist beliefs to the books. The writers, both big old hippies, wanted to keep Objectivism as far away from the comics as possible.

In 1969, Steve Ditko gave his last interview. He would bounce around from publisher to publisher for the rest of his career, including occasional work with Marvel and DC. Any fan of Ditko can see his work declining not because of age, but because he just didn’t care about these for hire jobs. Ditko crapped out “good enough” work for the comics, and honest to God garbage for other things, like a Transformers coloring book.

In 1987, Steve Ditko was awarded the Comic-Con International Inkpot Award. He didn’t show up for the ceremony, so publisher Deni Loubert accepted it on his behalf. Loubert sent the award to Ditko, only to have it returned with a note that read “Awards bleed the artist and make us compete against each other. They are the most horrible things in the world. How dare you accept this on my behalf”.

In 1998, Ditko pretty much retired, only working with his longtime friend and editor Robin Snyder. These days, Ditko and Snyder continue to self publish comics, using Kickstarter to raise the funds. They’ve consistently kept the Kickstarters at low asking numbers, below five grand each time, but they’ve done quite a few. I can’t imagine they’re making much off of these books, so you know they are doing it for the love of creating.

Ditko turned 89 this year, and we know very little about his life these days. We know, or at least we’re pretty sure, he still lives in Midtown Manhattan; we know he still has an office there, and word on the street is that he lives in a hotel close to his office, but others claim he lives in his office. While we know he never married, we think he has a son, though his “son” may actually be his nephew. As far as the world can figure, only one person, Will Eisner, has ever met Ditko’s “son”.

In 2012, Reed Tucker tracked Ditko down hoping to get an interview. Ditko politely refused, though he did answer one question; was he receiving any of that crazy Spider-Man cash? Between the comics, toys, cartoons and movies, Spider-Man is a billion dollar brand.

Ditko made it clear, he hasn’t received a single penny. More to it, he doesn’t seem interested in making any money from his creation, or any of his other creations for that matter. According to Greg Theakston, an artist and editor who has worked with Ditko in the past, the guy has stacks of original pages from his work on The Amazing Spider-Man as well as his other books, and he uses these stacks as cutting boards. Ditko knows that he could sell these pages and make millions, but he just isn’t interested.

At some point, Ditko and Lee repaired their relationship, though it fell apart again when, in 1999, Lee said that he considered Ditko to be the co-creator of Spider-Man. Ditko took offense at the use of the word “considered” and has since refused to speak to Lee.

Steve Ditko has lived his life following his Objectivist beliefs. He refused, and still refuses, to profit on his past work. I suppose in doing so he is following the Objectivist code, which in part states “productive achievement is man’s noblest activity and reason his only absolute”. In fashioning his life on the writings of Ayn Rand, Ditko has become the John Galt of comics, a great talent who could not bring himself to compromise his work. Unlike Galt, anyone can find Ditko - his office address is listed in the phone book and easy to find. Over the years, many fans have made the pilgrimage to Ditko’s office to talk comics and maybe get a few signed. Instead, they have only received hours long discussions about politics and a refusal to sign anything.

I’ll let Steve Ditko end this with his own words, recorded for the documentary The Masters of Comic Book Art.

*Robinson, like Ditko, is an artist who has never gotten his proper credit. While Bob Kane got all the money and fame from the Dark Knight Detective, it was Robinson and writer Bill Finger who did most of the work, including creating Robin, Alfred, Two-Face, and the Joker.