The Great Debate: SPLIT

Last week we announced The Great Debate for Split, M. Night Shyamalan's psychological thriller in theaters now. If you're not familiar with The Great Debate, we bring on two writers to discuss a new release. There are SPOILERS here, so this is intended for discussion only for those who have seen the film. Haven't seen it yet? Go see it first, at the Alamo or elsewhere, and then come back.

Today, we've got The Austin Chronicle's Richard Whittaker and our own Andrew Todd on the mat to debate Split and its director, M. Night Shyamalan. Weigh in with your own take in the comments, and don't forget to vote in the poll!

M. Night Shyamalan gets a bad rap. His bizarre ideas often invite derision, but you can’t argue that he throws anything less than 110 percent at them. With Split, he's made an origin story for a villain, driven by a hyper-charismatic performance and a hyper-#problematic psychological M.O., that apparently exists in some kind of M. Night shared universe. It’s one hell of a strange movie, and one for which I have a lot of fondness.

Now, I’m coming to Split from duelling perspectives: that of a passionate genre fan, and that of someone who suffers from mental illness and is sensitive to unsympathetic depictions of it. With this film, those two perspectives can be hard to reconcile, and even harder to articulate. I’ll do my best.

Shyamalan has gone through three distinct phases in his career. First, he was The Twist Guy, shocking and delighting audiences to varying degrees with The Sixth Sense, Unbreakable and Signs. The Village sparked Shyamalan’s transition into The Flop Guy, a phase dominated by passion-project misfire Lady in the Water and director-for-hire disasters The Last Airbender and After Earth. However, the other film from that period - The Happening - bore many of the hallmarks that define Shyamalan’s latest output. Now, Shyamalan makes high-concept genre fare that, if released in the ‘70s, would be hailed today as exploitation cult favourites. The Happening, The Visit and Devil (which Night only produced) are strange, fun movies, and Split is very much in the same vein.

Split belongs to a specific family of exploitation that exploits cheap, popular and outright wrong interpretations of psychology - films like my personal favourites The Love Butcher and The Psycho Lover. All of these films present their psychological conceits as hard fact. None of them are even remotely medically accurate. Though that’s certainly “problematic” in that it can perpetuate damaging ideas to people with zero disconnect between fiction and reality, there’s a perverse sense of entertainment to be found in films built on ideas that are that profoundly wrong. Those films simply wouldn’t be as much fun without their stupid, cartoonish misinterpretations of science. And neither would Split.

Split deals chiefly with dissociative identity disorder - a disorder that’s poorly understood even amongst the medical community. I certainly don’t know much about DID, and clearly, neither does M. Night Shyamalan, though his script does at least make overtures towards its misunderstood nature. The film’s main character, Kevin (or The Horde), has 24 separate identities - one of which, The Beast, is capable of changing Kevin’s DNA to make him bigger, stronger, impervious to shotgun shells and capable of climbing sheer surfaces. The Horde’s goal is the eradication of all who are “impure” - all who haven’t suffered trauma of some kind, like Kevin did at the hands of his mother. Or like his abductee Casey (Anya Taylor-Joy) did at the hands of her uncle. For the Horde, traumatized people are more evolved; they represent a transformation into something greater.

Somehow, then, Split both demonizes AND ROMANTICIZES mental illness and the effects of abuse, pushing it from “problematic” into full-on supernaturally fucked up territory. This movie pushes so many buttons, it either has no idea what it’s doing, or knows exactly what it’s doing, and I’m willing to bet it’s the latter. If Kevin/the Horde had merely been a killer with DID, or had been delusional about the sci-fi elements of his character, the film would be far more offensive - it’d be a character who could plausibly exist in real life. But the drop it takes into the realm of science fiction is transcendent. Casey’s storyline is lacking by comparison - it’s missing a concluding narrative beat, for one thing - but it develops alongside the Horde’s, abductor and abductee forming a unique and oddly poignant empathy for one another. This is all way outside any conventional approach to a psychological thriller, and it’s definitely got issues - but those issues are just unique enough to work.

Split also works as a roller coaster ride of genre subversion and off-kilter entertainment. Shyamalan’s movies frequently sport central conceits so silly they border on the deranged, but he absolutely commits to them, and Split has an assured, if idiosyncratic, hand at the controls. It’s nearly impossible to tell where the movie’s going in its first hour, so precisely does Shyamalan toy with the audience’s expectations.

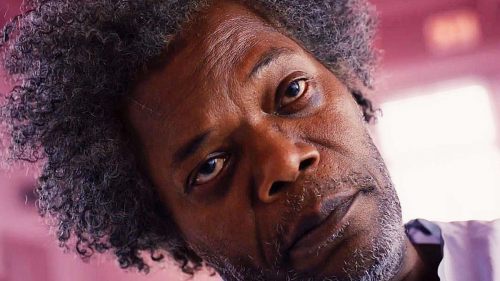

James McAvoy’s remarkable central performance - itself reminiscent of great exploitation performances like Erik Stern’s in The Love Butcher - sees the actor play at least half a dozen distinct characters. Each one is laden with unique tics and expressions, and seeing McAvoy dance between them is riveting to watch. Anya Taylor-Joy, unrecognizable from her performance last year in The Witch, is a suitably strange presence in the film, playing Casey emotionally disconnected so as to heighten the impact of the story’s eventual revelations. And Betty Buckley (so memorable in her brief role in The Happening) does sterling work with difficult material, at one point literally monologuing the film’s premise direct to camera for what seems like a good five minutes.

Those key performances are brought together by Shyamalan’s peculiar writing and directing style. Shyamalan’s idiosyncrasies have gotten more pronounced and refined with time. The batshit weirdness of The Happening is now a more focused weirdness in Split: the unmotivated symmetrical shots, dolly zooms, wildly overwritten speeches and silent, uncomfortable pauses all come out to play and, boy, do they play. It’s hard to even call it “bad filmmaking” anymore, since it’s both incredibly entertaining and clearly exactly what Shyamalan wants to do.

Since it’s all anyone talks about when the credits roll, it’s vital to discuss Split as a stealth sequel; a piece of franchise-building; a work of inter-film storytelling. Though the film would function without it, the mid-credits tag that connects Split to Unbreakable completely recontextualizes the film’s genre and place in Shyamalan’s oeuvre. Clearly, Shyamalan is building a tiny shared universe of sorts, with a “versus” movie sure to be incoming. There are so many questions. How will Mr Glass, currently in an insane asylum, factor into the story? How far will the shared universe go? Will Unbreakable Bruce Willy team up with Sixth Sense ghost Bruce Willy and defeat the Horde through therapy? All bets are off after an act of self-reference so ballsy it feels like a middle finger to Marvel.

Revisiting Split as a companion piece to Unbreakable also reveals hidden layers to Shyamalan’s agenda. What was once a horror-thriller suddenly becomes an origin story for a supervillain that mirrors Unbreakable’s hero. Finally, we get to spend an entire feature narrative exploring the psychology of a supervillain, without any heroes to muddy the waters. Just as the treatment of DID would be more problematic without the supernatural element, Kevin/the Horde would be far less compelling - and, frankly, sympathetic - without this time spent developing them. When the Horde does eventually face off against David Dunn, there’ll be real weight and history behind both characters. The best villains are the ones we secretly root for, and the empathy underneath the Horde is more developed and interesting than the simplistic backstories most villains receive.

Despite its unsettling thematic and narrative tropes, Split is a weird and entertaining ride, strewn with peculiar choices that I can’t help but love. I even like how much blatant pseudoscience there is. As far as defences go, it’s probably a cop-out to say I like Split for the same attributes that make many dislike it, but that’s the situation in which I find myself. I love this kinda-stupid, kinda-touching, completely-wrong movie, and I’ll be first in line to see the sequel.

There’s a moment in M. Night Shyamalan’s Split where the pieces fall apart. It’s when one of the plethora of personalities created by Kevin (James McAvoy) instructs the three teenagers he has abducted to take their tops off.

There is a trivial plot reason for this. But it really occurs because that’s what happens at that moment in a middle-of-the-road horror movie. You get half an hour in, someone gets topless.

The trite criticism of Shyamalan has always been the twist ending. It’s become a cinematic meme (when you’ve been mocked by Robot Chicken for it, you know have a problem), but it’s never been something with which I have had an issue. Shyamalan has always rejected the God POV approach to storytelling, and that’s fine.

In fact, it’s essential to how he approaches fantasy. He is a genre director who deals with the character drama of facing the uncanny. Of finding out there are ghosts. Of discovering you are a superhero. Of waking up in the future. Like the characters, the audience a needs a revelation, and for a long while we were okay with that approach.

Yet somehow, the critical darling of the 1990s became a cinematic laughing stock, bottoming out with the hatewatchworthy Avatar: The Last Airbender.

But wait, he is in a revival. He’s a horror director now. We know, no one liked Devil, but he only came up with the idea, so is only passingly to blame. But with The Visit and Split, he’s on the megabucks express to goretown!

Yet these are not different Shyamalans. In his early works, he was riffing on established story forms, like he was trying to understand them. The Sixth Sense is in many ways a very conventional ghost story, but its genius is in trying to make the experience grounded. Signs is the everyman’s survival guide to alien invasion. The Happening is an admirable if flawed attempt to revive 1950s proto-eco horror for the modern era – it just ended up more like The Monolith Monsters than Day of the Triffids.

But there is a rupture in Shyamalan's career. It arguably came after the critical savaging of Lady in the Water, and accelerated post-The Happening. The second wave dribbled in with his execrable life-action adaptation of the beloved cartoon series Avatar. Devoid of humor and pathos, lumpen and misguided, it was the work of a director who did not understand action, or how to tell a complicated plot, or anything that made the show work. After Earth is the sort of idealess SF that gives YA fiction a bad name. As for The Visit, rarely have I been so angry at a film for totally misguided transgression. Horror extremists like Fred Vogel (August Underground) and Stephen Biro (American Guinea Pig: Bouquet of Guts and Gore) can get away with having an unbalanced old man shoving a soiled adult diaper in a kid’s face because they know they are pushing buttons. For Shyamalan, it’s a throwaway sight gag.

He has stopped trying to illuminate genre, and just started doing it, with a myna bird’s eye for mimicry. The shirts come off because that’s what happens at that moment in a middle-of-the-road horror film.

Imagine a movie is a clock. Shyamalan has spent his life crafting beautiful, erratic, baroque custom pieces. The Sixth Sense and Unbreakable are masterpieces in operation: crack open the back, and the detail in every cog is extraordinary. Even when they don’t keep time particularly well – Signs, The Village – they have moments of bizarre gorgeousness, like a hand-carved cuckoo clock that chimes backwards. Seriously, tell me the calm, suicidal bodies hurtling towards the camera in The Happening doesn’t send a chill. But his newer work is a hotel alarm clock – generic, mass produced, easy to use and easy to leave behind.

Maybe this is a defense mechanism. When faced with critical and audience backlash, George Lucas’ response was to hunker down, re-enforce his vision for Star Wars, get his long gestating passion project Red Wings done, then declare a plague on all our houses and put up the ‘for sale’ sign on Lucasfilm. By contrast, Steven Spielberg has flailed between genres in a quest for renewed relevancy. Shyamalan’s response seemingly is to give up and give the audience what he thinks they want.

The victim of this change is his compassion. Shyamalan’s early work was defined by a touching humanity, of ordinary people finding some grace in extraordinary circumstances. Even Unbreakable’s Mr. Glass is a tragic figure, a self-made supervillain because he wants to find a superhero. Both The Visit and Split have an ugly mean-spiritedness, with the senile and insane wreaking malevolent depravity on bland teens.

That Shyamalan falls back on disability as the trigger for evil seems particularly disturbing. News flash, Night: Dr. Doom isn’t a villain because he’s disfigured. He’s disfigured because of his villainous actions.

Almost perversely, the greatest redeeming feature of Split is undoubtedly McAvoy. His character-hopping one-man show reminds that Shyamalan’s strength has always been as a director of actors: bringing out a rarely-seen brittle strength under Bruce Willis’ wisecracking persona, or letting Mel Gibson speak in subtle silences. McAvoy finds ways to create sympathy and terror through the different aspects of a man at war with himself. But Shyamalan the emulator can’t resist himself, and the reveal that this is not a serial killer movie, but the birth of a multiple-personality multi-powered supervillain, makes anyone paying attention go, “So, you couldn’t get the rights to Marvel’s Legion?”

So is my anger that a daring director has become workmanlike and derivative? Yes, absolutely. Because if all he’s doing with horror is taking shirts off when shirts are supposed to come off, the genre of visceral ideas becomes the genre of screenwriting equations.

Now you've read the arguments, and it's time to make your own voices heard. Team M. Night Or Team M. Not?