Who’s The Best Android In The ALIEN Franchise?

Welcome to our next installment of The Great Debate! Today we have Scott Wampler and Jacob Knight arguing on behalf of their favorite androids in the Alien franchise. Scott's Team David from Prometheus and Alien: Covenant, and Jacob's stumping for Aliens' Bishop. Jump in with your own vote in our poll below, and feel free to holler for Walter, Ash or Call in the comments!

A note on spoilers: they abound! So make sure you see Alien: Covenant before joining in the conversation.

First up, Scott FOR Alien: Covenant:

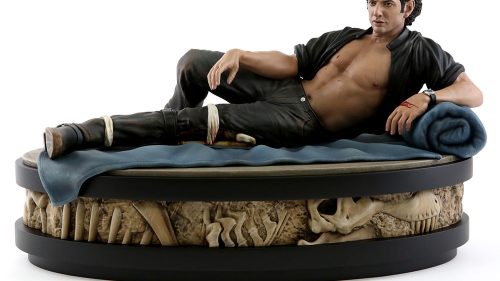

Whereas we once championed the heroism and selflessness of Lance Henriksen's Bishop - a worthy and noble pursuit, to be sure, because Bishop was, is and will always be ya boi - the newest string of Alien movies has given us someone (something?) far more interesting: Michael Fassbender's David, the lovable scamp who poked, prodded and straight-up poisoned his way through the events of 2012's Prometheus.

Adopted into the distinguished Weyland family by no less than Peter Weyland himself, designed to be more human than human, and capable of creating things at will (whoops!), David - full name David 8, if ya nasty - is also a complete and total dick. In Prometheus, his list of crimes includes: pushing every goddamn button he comes across, secretly absconding from the Engineers' temple with an ampoule filled with a hideous black DNA-remixer, infecting poor Holloway with it, and just standing there uselessly while his de facto father gets his head ripped off by a jetlagged Engineer. There can be no doubt that David is less helpful than Aliens' Bishop.

The hijinks continue in Ridley Scott's follow-up, Alien: Covenant, where we learn that David spent the decade following Prometheus on his very own planet, satisfying his seemingly unending curiosity. He's got any number of ways to do that - kicking back and writing music on his homemade flutes, drawing pictures of his various science experiments, wiping out an entire frigging civilization - but when we pick up the thread of his storyline, it's clear that David's taken things as far as they can possibly go. Without new humans to experiment on (he already spent the one human he had on-hand), David is delighted to see the Covenant crew show up on his turf. Finally, something new to play with!

I won't further spoil what David gets up to in Alien: Covenant, but rest assured that he does some very naughty things, indeed (come to think of it: David may be the deadliest thing in the entire Alien franchise, at least that we're aware of). But he ain't all bad: he's also a talented musician, he's able to pilot spacecraft which were absolutely not designed with him in mind, he can speak virtually every language in the galaxy, he likes Lawrence Of Arabia, he knows how to cut his own hair, he's almost always polite, he's pretty damn loyal, and he's not afraid to drop the word "fingering" into casual conversation (oh, and - as proven by Prometheus - he has mad bartending skills). Sure, all that terrible stuff I mentioned before far outweighs the positive David brings to the table, but that doesn't make him a bad android.

Quite the contrary! I believe David's nearly limitless resourcefulness and his pronounced talents for creation, investigation and planning (you might call that "scheming," but let's not get caught up in the details) make him the franchise's best android.

Of course we can interpret that title any number of ways (the most common will be: is he a good robot or a bad robot?), but if you really think about it, the best android oughtta be the one with the most features and the least inhibitors, the one with the greatest potential. I submit to you that no android - not even our beloved Bishop (WE'LL ALWAYS MISS YOU BIG POPPA) - has ever shown the potential that David has. Nor has he accomplished a fraction of what David has accomplished. Would you really want an android like David around? Well, probably not, but lucky for me that's not the question I've been tasked with answering.

The obvious problem with designing an android who's better than human beings in almost every conceivable way is, sooner or later that android's gonna start wondering why it has to answer to you. And if, like David, that android has the ability to create new things - be they drawings, headstones, flute songs or just some good ol' fashioned genetic abominations capable of ripping you to pieces before you can even raise your pulse rifle - sooner or later he's also going to wonder if it can't improve upon you. This represents something of a problem, to be sure, but from where I'm standing, such an android also represents peak performance, bleeding-edge technology and undeniable superiority.

So, how do you solve a problem like David?

You don't. David solves you, motherfucker.

Respect that and stay the hell out of his way.

--

And now we have Jacob, who's arguing for Bishop but we have limited graphics here so we'll just call it AGAINST Alien: Covenant.

The guiding motto of the Tyrell Corporation in Ridley Scott’s monumental ’82 sci-fi masterwork Blade Runner is “more human than human”; a rather ironic slogan for a company who manufactures limited lifespan replicant androids which are (as of 2019) exclusively utilized in off-world labor considered too menial or dangerous for mere mortals. When these skin-jobs defect and go rogue, it’s the task of the titular noir gunmen to shoot on sight. When they yearn for freedom, the biomechanical drones are put down with extreme prejudice and without remorse. There’s no regard for the fact that man made them in their own image – a worker ant plays on humanity’s constant need to replace God with themselves, whilst never paying any mind to the notion that these new beings possess their same hopes, desires and dreams as we do.

Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer) and his ilk are indirect offshoots of a creature Scott was already fascinated by in Alien (’79) – his haunted house space horror movie that harnesses one of its very best scares around Ash (Ian Holm), the Weyland-Yutani Corp. science officer who doubles as the company’s nefarious sleeper agent. Ash’s true synthetic nature is revealed via a defect, and his post-meltdown admittance of admiration for the xenomorph’s “purity” unveils just how anti-human he is. Ash is captivated by the being’s status as the universe’s constant survivor, an entity which is “unclouded by conscience, remorse, or delusions of morality.” The skin-job’s objectivity is his true soul – an observer who does not care whether Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) and the rest of the Nostromo’s crew lives or dies. Retention of the xenomorph is Priority Number One for W-Y, and Ash is capitalism’s operative, slaving away just like the Replicants did to return this Lovecraftian force of death back to his human masters on Earth.

This unfeeling robot’s chilling final transmission (“I can't lie to you about your chances, but...you have my sympathies”) echo through the cosmos and reverberate off the sterile walls of the USS Sulaco’s mess hall when we’re first introduced to Bishop (Lance Henriksen) in Aliens (’86). Another product of W-Y, his essence isn’t up for debate – the Colonial Marines being transported on this Conestoga class starship even count him as a friend, laughing hysterically as Bishop “does the thing with the knife” and sends Private Hudson (Bill Paxton) into a wide-eyed fit of hysterics. Ripley is none too pleased to find that it’s now standard protocol for every mission to be equipped with an android (though Bishop prefers to be called an “artificial person”), but the kind-eyed creation assures her that previous models like Ash’s were a little “twitchy”, and that he could never harm nor, through course of action, allow a human to be harmed during their journey together. Protection takes utmost precedence; a safeguard that instills a greater sense of humaneness in this latest technological fabrication of humankind.

Bishop is the quintessential James Cameron synthetic protagonist – a precursor to the same rabbit the writer/director pulled out of his hat when molding a sequel to his own lo-fi masterpiece, The Terminator (’84). Just like he would with Arnold Schwarzenegger’s T-800 in Judgment Day (’91), Cameron is upending our expectations regarding how this new android operates, and Henriksen helps accentuate the android’s immortal tenderness with his subtly nuanced performance (no robot has ever possessed optic implants this soft). Every line he delivers is soothing in cadence – a consummate reminder that everyone will be OK, so long as he’s on the lookout. Where Ash was installed to ensure the corporate mission would not be interfered with by human X-factors, Bishop disregards all other priorities but the human lives at stake. He’s a multi-purpose machine; able to pilot a spacecraft, administer medical attention, and dissect the insect-like creature they find in one of the test tubes in LV-426’s terraformed colony. Yet above all else, he is a protector, ensuring that the Conestoga is kept whole.

This somewhat myopic-mindedness certainly renders Bishop a less complicated character than David (Michael Fassbender), the TE Lawrence-obsessed droid from Prometheus (’12) and Alien: Covenant (’17) who becomes obsessed with the universe’s Engineers’ ability to transmute lifeforms like putty, and basks in the icky glory of creation as it unfolds in real time. But Bishop is the refutation of this very instinct (and an upgrade on David’s “brother” Walter) – Cameron’s obsession with technology working for man instead of against him (which, when married with the filmmaker’s undying pursuit of next level craft, explains the approach). When the core of LV-426’s atmospheric processor is punctured during a firefight between the Marines and xenomorph hive workers, Bishop volunteers to crawl through miles of claustrophobic piping and remote pilot the escape craft so that the survivors may dodge the impending thermonuclear blast. When Ripley and Newt (Carrie Henn) clutch each other, knowing death is descending on them in the form of a hulking xeno queen, it’s Bishop who swoops in and saves the day, flying off into the stars while a planet explodes in their wake. If we’re being completely honest, Ripley may be the unassailable icon molded by Cameron’s Aliens, but Bishop is its true last second hero – lending a hand when the odds become utterly insurmountable.

Without David, there would be no Bishop. But without Bishop, there would be no more Ripley. When God made man, he did so in His own image, and when David fooled with the practicalities of creative divinity, he became a flawed mad scientist, fueled by casual condescension flung at him by his human counterparts. His own sense of grinning objectivity combined with personal devaluation to lead him down a path to Hell, when all his crewmates wanted was to reach Paradise. Bishop is the perfection of this early mold – the failsafes installed in his central processor lending the artificial person an element that David strove to own: a true replication of a human soul.

In Battle for the Planet of the Apes (’73), a soldier comments regarding the evolved, talking primates, “speech makes them intelligent, and intelligence makes them not human, but humane.” This same notion applies to the Alien franchise androids, only replace “speech” with “responsibility.” After arriving back to the Conestoga, Ripley touches Bishop on the shoulder and tells him how well he did, prompting a tiny smile out of the robot. It’s in this small exchange that we understand the depth of his sentience, and desire for acceptance by those he strives to keep safe, rendering his subsequent dismemberment at the claws of the queen that much more heartbreaking. He’s closer to his creators now, and Cameron forces the audience to watch Bishop die in graphic, painful slow motion.

The soul this artificial person solidified in Aliens would be locked in darkness following the queen’s attack, even as Ripley reconnects his central processor to check the black box recordings of Newt and Hicks’ doomed life pods in Alien 3 (’92). After delivering the requested information, Bishop begs for death – preferring to be kept offline than endure this impenetrable nothingness any longer, a pulp take on assisted suicide, staged in the junkyard of a prison planet (thus feeding into David Fincher’s grim funeral procession tone). His purpose can no longer be achieved due to his form’s irreparable damage, but his spirit lives on, trapped inside circuits that can be switched on with a crude life-supporting battery. Here we see ourselves in Bishop, and must pose the question as to what we would prefer should the same fate befall our mortal bodies; empathy achieved with a lifeform that has yet to be invented during our current timelines. More human than human, indeed.

--

Now it's your turn! If you're team David, Bishop or other, vote below and defend your choice in the comments.