Sunday Reads: American Jesus - ROBOCOP At 30

Back in ’07, Paul Verhoeven wrote a scholarly treatise on the historical Christ, Jesus of Nazareth. With his text, Verhoeven casts doubt upon the many miracles Jesus performed in the gospels, utilizing direct passages to discredit such acts as walking on water and the Resurrection. The provocative Dutch auteur believes that it’s not a matter of divinity that should be revered, but rather Christ’s set of ethical principles, which became a model for millions in the wake of death and canonization. “It isn’t because of his healings,” Verhoeven told New York magazine, dressing down the perceived Son of God, “because humans now possess the healing technology 100 times, 1,000 times what Jesus did. What we are left with is what he said, the parables, the moral thinking, because when you study Jesus’ life, as the miracles fall away as physical impossibilities, you learn that the quotes, the speeches and the reasoning behind them, for the most part, are genuine.”

Cinematically, Verhoeven has crisscrossed the divine and the secular on numerous occasions, most notably in his Dutch precursor to Basic Instinct (’92), the polyamorous love triangle thriller, The Fourth Man (’83). Boozy bisexual novelist Gerard Reve (Jeroen Krabbé, from Soldier of Orange [‘79]) exits Amsterdam to deliver a lecture at the Vlissingen Literary Society. During his stay, Gerard has an affair with the municipality’s Hitchcock Blonde treasurer, Christine (Spetters’ [‘80] Renée Soutendijk), who may also be a black widow murderer. At the same time, the writer is attracted to Christine’s other lover, Herman (Thom Hoffman), whom he attempts to seduce. During these sexual overtures, Gerard has visions of the crucifixion, in which the man on the cross is molested, and the Virgin Mary appears to him, warning that Gerard will be Christine’s next victim if he doesn’t heed her warning. The writer passes this message on to Herman, who ignores the blasphemous admonition and is killed for his “sin.”

Verhoeven states that The Fourth Man is a filmic depiction of his overall views regarding religion. The writer/director is quoted as saying that Christianity is “one of many interpretations of reality,” and that overindulgence in it, or any intoxicating vice (such as sex or violence) can cause a spell of “super-reality.” Fantasy and everyday existence become intertwined to the point that they’re indistinguishable – a mash of distorted POVs so overwhelming that one can become confused with the other. This helps explain the filmmaker’s need to write a tome which seeks to demystify the belief in Jesus Christ as a sort of mystical super-being. Instead of extracting the messages from the Lord and Savior and living by them, His followers are more fixated (in Verhoeven’s mind) on the “super-reality” his set of miracles help buttress. A fervent believer in cinema, Vehoeven has admitted that Jesus of Nazareth was nothing more than a “treatment for a film” that he found financing for in ’12, and was going to be aided in the scripting process by Pulp Fiction (’94) co-writer, Roger Avary. Sadly, that project fell apart, and it would take four more years before we received Verhoeven’s next proper narrative in Elle (’16)*.

However, it’s difficult to become overly depressed about losing Jesus of Nazareth, as Verhoeven had already delivered his defining portrait of Christ in RoboCop (’87). His second American feature for Orion Pictures (following the Crusades fiasco Flesh + Blood [’85]), Verhoeven brought the bloodshed from his breakthrough Dutch picture, Solider of Orange, and married it with his earliest cinematic memories growing up during the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands. Propaganda films played in cinema houses while the Germans held power, and Verhoeven’s relayed stories about discovering the bodies of shot down pilots in fields behind his boyhood home. When viewed through this lens, the satirical television broadcasts that break up RoboCop’s stretches of squib-laden ultraviolence make perfect sense. This was the stylized product of a mind that drew from popular entertainment and militaristic transmissions of insidious evil in equal measure. So, when it came time to stage Christ’s resurrection, he packaged it inside a movie made up of elements drawn from two mainstream filmic molds – comedies and action movies.

“RoboCop’s an American Jesus,” Verhoeven told Esquire during an oral history recorded in ’14. “I don’t believe in the resurrection of Jesus in any way. But I can see the value of that idea; the purity of that idea. So from an artistic point of view, it’s absolutely true.” Tongue tied and somewhat confusing as that sentiment may seem, when taken in time with the text of RoboCop, it’s easy to see what the Dutch madman means. Officer Murphy (an iconic Peter Weller) is a good cop in Old Detroit with a wife and kid who idolize him. On the streets, he’s a brazen gunslinger, joining his partner (Nancy Allen) on a hunt that goes horribly wrong. Once discovered, the patrolman is graphically executed by Clarence Boddicker (Kurtwood Smith) and his band of giggling thugs. They shoot off Murphy’s hand before blowing his brains out all over a warehouse floor, his arms spread in the form of (you guessed it) Christ on the cross. It’s a savage bit of torture and murder that sets the tone for this large caliber fantasy, the peace officer’s corpse soon the subject of an experimental procedure that will give him life and make him superhuman.

The fact that the operation is masterminded by a corporation only helps reinforce the “American” aspect of Murphy’s Christ status. Omni Consumer Products – led by Senior President Dick Jones (Ronny Cox) – is looking to improve upon the Enforcement Droid Series 209 (or ED-209, for short) after a disastrous boardroom test run that left one employee machine-gunned to death. The mortality rate in the Detroit Police Department has skyrocketed, and even though he’s quoted in the media as telling the cops “if you can’t stand the heat, get out of the kitchen,” Jones’ pet project is a disaster. Sure, it’s a “minor glitch” in ED-209, but ambitious exec Bob Morton (Miguel Ferrer) views the fuck-up as an opportunity to swoop in and convince the Old Man (Dan O’Herlihy) that it’s time to take the concept of a mechanized law enforcement agent in a new direction.

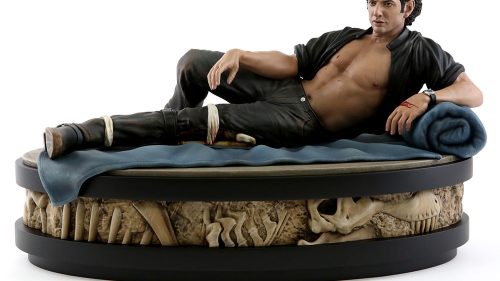

RoboCop is essentially the product of the most American ideal: capitalism. Murphy’s fate is even predetermined by his Overlords, as Morton informs the Old Man that prime candidates for the program have been reassigned to higher risk areas of the city. The first time we meet Murphy, he’s reporting for his first stint of duty in one of Old Detroit’s problem zones. Just as the Divine Christ was chosen to die for our sins by his Father, RoboCop’s existence was put into motion by Higher Powers; a destiny designed by men in suits looking for a savior to clean up and patrol their dream domain – Delta City, a white castle replacing these dark and dingy streets. Soon after, Murphy’s mangled form is fused with state of the art technology and, though his memories have been wiped and replaced with patrolman programming, we still recognize the face of the slain officer stretched out across a metal skull. He is risen.

There were nearly 33,000 gun deaths in America in ’87, a statistic that would almost break 40,000 by ’93. When RoboCop patrols, he serves and protects via a hand cannon that’s stored inside one of his shiny legs. Not only has Verhoeven cinematically proven (via the assistance of sci-fi) his own theory regarding the healing power of humans twenty years prior to publishing Jesus of Nazareth, he’s subverted Christ’s “turn the other cheek” ethos by having this weaponized savior incapacitate Detroit’s criminals via vulgar displays of power. Upon catching two rapists assaulting a roman, RoboCop doesn’t just incapacitate them. He shoots one of the men in the dick through their victim’s skirt before flatly intoning to the other, “your move, creep.” But the limitations of a God empowered solely by violence are quickly displayed, as he cannot comfort the woman and instead simply refers her to a crisis center. Physically, she’s alive. Spiritually, the cyborg’s no help.

Yet the memories of Murphy’s former life begin creeping back, as no amount of rewiring can prevent the human soul from penetrating even the most complex artificial intelligence. Officer Lewis (Allen) inadvertently pries at the ghost in this machine, causing RoboCop to twitch and glitch. But the true short circuit comes when Murphy revisits the home he built with his wife and child. Verhoeven credits the scene in Ed Neumeier’s original script as being the one that convinced him to make the movie (after throwing it in the trash, where his wife fished it out and discovered the document’s “soul” while he swam at Côte d'Azur). “That to me is like finding the lost Garden of Eden, like a lost paradise,” Verhoeven said of the melancholy scenario, and you can feel the raw emotion pulsing through that moment as it plays out on screen. The God is remembering what it was like to be a man, and the ethical code he adhered to as a human police officer returns and starts to push back against his corporate programming.

RoboCop’s chief adversaries are also under the influence of office politics. Boddicker and his crew take money from OCP higher-ups and spit blood on cops’ desks (in a moment that was improvised – like many of Boddicker’s best bits were). Playing second fiddle is a bright-eyed Ray Wise (as Leon Nash), former henchman to Frank Booth in David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (’86) just the year before. Joe Cox (Jesse Goins) chuckles his way through atrocity, while Steve (Calvin Jung) and Emil (Paul McCrane) add specific flamboyance, both looking like they climbed out of a blaring, sweaty punk show. These miscreants are the grime merchants outside of OCP’s Temple – a comic book collection of Reagan-era ruffians that bring real flare to Verhoeven’s decaying, hedonistic metropolis.

Guarding that castle is arguably Rob Bottin’s greatest creation. Already a legend thanks to classic horror makeup showcases like John Carpenter’s The Thing (’82) and Ridley Scott’s Legend (’85), Robocop explores an array of robotic monstrosities. When combined with Phil Tippet and Pete Rozani’s ED-209 stop motion sequences (not to mention William Sandell’s trash brutalist production design), we feel the texture of this lo-fi world. Bottin’s countless blood squibs caused RoboCop to get slapped with a dreaded ‘X’ rating eight times (a number Verhoeven insists keeps getting embellished and “mythologized” with each passing year). Old Detroit is a universe of gleeful carnage, as Basil Poledouris’ soaring themes inject a sense of perverse adventure into the proceedings.

Nobody said metaphors had to be subtle in order to be impactful, and the best symbols serve as a solid foundation, on which auteurs like Verhoeven can craft their ultimate “super-realities.” RoboCop is about as divine as Verhoeven believes Jesus of Nazareth to be – a God whose humanity saves him in the end. Alex Murphy becomes a symbol in RoboCop as much as he’s a protector of man against his own worst enemy: other men. There’s a corniness to the movie’s ultimate to serve and protect messaging that acts as a reminder that cinema can sometimes lie to you from time to time (just like Nazi propaganda did to the filmmaker when he was a child). In a country that saw incidents like the ’67 Detroit Riots, the Algiers 7 brutality case of ‘80, and Contra cocaine trafficking acknowledged in ’86, authority and all the violence it brings with it is not to be worshipped, as police have caused enough pain to the disenfranchised in this country. American Jesus stands for something, but he’s still just a killer robot who remembered how to be a man. Verhoeven had subverted religion yet again, and transformed the results into ruthlessly thrilling pop art.

*As intriguing as Verhoeven’s Tricked (’12) is, the film’s experimental nature disqualifies it as a ‘proper’ narrative feature.