What Next For DC?: On JUSTICE LEAGUE’s Box-Office Disappointment

It was no secret that Superman would be part of Justice League, yet he was hidden from the majority of the film’s marketing despite being teased at Comic Con 2016 and at the end of Batman v Superman. Folks in the know were attuned to what the deal was – any comics fan can tell you no one stays dead, least of all Superman – but one couldn’t help but get the sense that his presence was being hidden from general audiences in order to sell the movie, or rather, to avoid turning people off it. Of course, one writer’s speculation means little in the face of the industry machine. Henry Cavill features in a mere six scenes in the finished product (then again, Civil War featured Spider-Man in two and he got his own trailer moment), but that this is even a plausible explanation means there’s something amiss in the DC Universe. If the inability to sell audiences on SUPERMAN isn’t indication enough though, Justice League’s resultant opening numbers certainly ought to be.

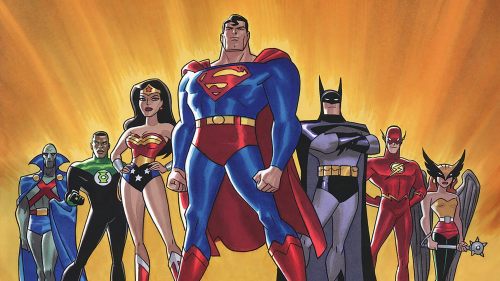

This weekend, DC’s superhero team-up movie made $94 million dollars at the domestic box office. That’s the lowest of any film in the series, missing Wonder Woman, Man of Steel and Suicide Squad by about $10 million, $20 million and $40 million respectively, and falling short of its own predecessor (the film that introduced DC’s Trinity: Batman, Superman and Wonder Woman) by an entire $70 million. If one is so inclined, one could point to Justice League opening bigger internationally than those first three films with $281 million, but even its worldwide numbers fall short of Batman v Superman by a significant margin (about $140 million). Now, these numbers mean little without context of course. Box office haul isn’t automatically indicative of quality (just ask the Transformers series), but for a film like Justice League, an installment featuring key players meant to fast-track DC’s shared-universe culmination and set up a dozen forthcoming films, a number equal to Marvel’s Z-list Guardians of the Galaxy in 2014 and lower than Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man back in 2002 is downright abysmal.

How did we get here?

Much to the chagrin of people caught up in the (mostly imaginary at this point) DC-Marvel flame war, the aforementioned context for these figures must, in fact, include Marvel Studios. For one thing, the two series are speaking the same language to general audiences – superhero shared universe! – only one of them has succeeded in their branding, to the point that it’s not unheard of for folks unfamiliar with the comics to refer to Wonder Woman, Justice League and the likes as “Marvel movies.” Is that out of confusion over who owns which property? Sure, it could be. People call Fox’s X-Men series “Marvel movies” all the time, though there’s more precedent there given the logos and source material, and since it could be technically correct. Conversely though, you’d struggle to find too many people referring to a given Marvel property as a “DC movie” since the Marvel brand, like brand names Xerox or Band-Aid before it, is slowly becoming a catch-all term for the product itself. For some folks, a superhero movie is simply a “Marvel movie” now. More pertinently though, Marvel is a money-making machine at this point, and given the similarities of the source material, DC’s attempt at building a shared cinematic universe was contextualized in relation to Marvel Studios from the start.

After Iron Man and a handful of other surprise successes, Marvel’s The Avengers set the world on fire with an explosively enjoyable cinematic experience seen by plenty of folks who had never laid eyes on Marvel movie. It opened to a record-smashing $207 million domestically and nearly $400 million worldwide (falling short of only two other global hits, both of them late Harry Potter installments) before arriving at a gargantuan total of $1.5 billion. The only other superhero films to gross over a billion dollars globally are the latter Dark Knight entries, and Marvel’s own Age of Ultron, Civil War and Iron Man 3. Given that Marvel Studios didn’t have access to its A-list when it started out (Spider-Man, the X-Men and The Fantastic Four, all of which had enjoyed mainstream success in some form), DC using the Batman platform in addition to fellow A-listers Superman and Wonder Woman ought to have been a sure thing. And yet, we’re somehow at a point where Justice League could result in a $50 million loss for the studio.

By the time Marvel became the benchmark for shared-universe storytelling in 2012, Warner Bros. had already wrapped production on Man of Steel. This new version of Superman was always intended to be a “darker,” “more serious” take on the character a la the unprecedented smash-hit The Dark Knight, which granted the superhero genre a certain amount of legitimacy amongst critics and award bodies. By the time it came out, Iron Man 3 had taken the box office by storm, further cementing the Marvel brand as something that could function even without a major team-up. Regardless of whatever the initial intent might have been, Man of Steel was going to be read as an answer to Marvel, and potentially the first film in DC’s own shared continuity. By injecting it with philosophical musings (that is to say, by paying lip-service to Superman’s philosophical underpinnings) and by leaning into a gritty texture unseen in any mainstream superhero movie, the film was able to stand out regardless of the divisive response. It became a mission statement, one further crystallized by how Batman v Superman was packaged from the start (at Comic Con 2013, just a few months later), and that mission statement was that the DC Universe would be the anti-Marvel superhero franchise: more serious, more adult, and far less colourful.

The DC Universe had inadvertently promised fans what it wouldn’t be, but the problem therein was it still had no handle on what it would. Where The Dark Knight trilogy was, by modern blockbuster standards, an auteur endeavor, films like Batman v Superman and Suicide Squad felt more like corporate products (not unlike a vast portion of the Marvel output, though far more haphazard and chopped up), as opposed to the “filmmaker driven” universe that was constantly touted. The studio tried to deliver one thing, but fans began responding positively to another. Suicide Squad ended up massively retooled because people loved its slick, fun trailers and the movie they had at the time was nothing like that. The largely negative responses to Batman v Superman altered the fundamental nature of what Justice League would be just weeks before production, and the positive response to the markedly different tone and focus of Wonder Woman altered it even further amidst ongoing reshoots. All told, the film shot on and off for nearly a year and a half in the process of trying to figure out what the DC Universe wanted to be, because what it had largely been up until that point was pseudo-deconstructions of characters that didn’t actually exist in the movies.

Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns was a landmark for DC Comics in the form of socio-political commentary on Batman, but a major problem with using it as a starting point for Batman v Superman (even in texture) was that rather than feeling like the condensed, serious and intelligent take TDKR was in the ‘80s given the comic history of Batman at the time, it ended up a watered down version of the most recent Batman audiences had grown used to. Not only that, in addition to Nolan’s Batman trilogy being politically minded, it really did exist in a “realistic” setting. To attempt to make an interpretation feel “more” grounded and realistic while simultaneously inserting Batman into a world of Gods and aliens (the likes of which he’s never partaken in on screen) is a fundamental disconnect, and the filmmakers appeared to get around it by doubling down on the seriousness and making his entire ethos “I want to kill Superman.” On the other hand, this Superman didn’t have much going for him yet either beyond Batman-esque brooding and not really saving all that many people on-screen. (Justice League does have an answer to this in the form of retroactive retcon, which we’ll touch on in detail tomorrow.)

For more on how the Nolan trilogy and the aforementioned Marvel factors impacted superhero fandom, check out this in-depth thread by Twitter user @Acidic_Heart

Full disclaimer upfront: I am NOT talking about people who enjoy DC films, fans of DC characters, or anything like that. I'm friends on here with many people who like these movies. I'm talking specifically about the toxic folks who have ruined the reputation of DC fans.

— DoctorDoom (@Acidic_Heart) November 19, 2017

DC’s serious house of serious heroes was so joyless that Wonder Woman would’ve been a welcome relief even if it wasn’t half as good as it was. Luckily, it ended up being a film with its own unique identity, stemming from both a distinctly female lens (the likes of which mainstream studio cinema rarely sees) and an adherence to the ideas that had drawn readers to DC characters in the first place. Wonder Woman is a vital part of the DC pantheon, a set of God-like figures wrestling with and representing abstract elements of the human experience, and while the cinematic Superman had foregone the character’s focus on hope, Wonder Woman’s journey was centered entirely on belief in humanity. By this point, the problems with the DC movies that weren’t Wonder Woman were crystal clear. They weren’t actually about anything at their core.

Sure, Batman v Superman speaks the same language as Watchmen and Civil War (ideas of political responsibility as they relate to God-like beings), but it articulates them almost entirely in the form of news anchors speaking the subtext that ought to manifest in the form of story. Similarly, Man of Steel is a philosophical mish-mash that aims only to be a counter-Superman without first understanding Superman himself, and Suicide Squad is too convoluted to be about anything at all. While one can certainly levy similar accusations at some of the Marvel films, the key difference therein is that when Marvel puts out a work that feels low-stakes or thematically disconnected (for the sake of argument, let’s say Thor and Thor: The Dark World), the critical and general response still leans on the positive side. Why? Because Marvel creates characters that audiences actually like. They aren’t dour manifestations of anger in the body of superheroes, and they certainly don’t feel interchangeable despite most Marvel films adhering to a certain house style. These are characters people want to see interact with each other, and that’s a major part of why their shared-universe experiment works in the long run. Their brand is built on people giving a shit about their characters. Until now, DC’s has been built on little more than the hope that people would be hungry for an alternative.

While Justice League works overtime to course-correct this (its three new heroes are enjoyable highlights, and this new Superman seems like a decent person!), the unfortunate reality is it may not matter. Wonder Woman was beloved the world over, but even her presence wasn’t enough to bring people back, because the rest of this universe isn’t alluring or attractive despite this new film essentially being a low-stakes riff on The Avengers (with bits of Age of Ultron thrown in for good measure). While Wonder Woman has been the standout exception, a film that feels like a truly unique entry in the superhero genre, the rest of DC has merely been sliding along a scale with “Not Marvel” at one end, and “Marvel” at the other. Even 20th Century Fox has managed to make a couple of beloved movies of late (Deadpool, Logan) after a whole bunch of X-duds, with the horror-esque New Mutants on the way. When we’re reaching a point where there are five to seven major superhero movies a year, standing out both stylistically and thematically seems more important than ever, which is why even the “samey” Marvel films have been switching up of late.

It’s easier said than done of course, but Marvel having not seen diminishing returns a full decade in is testament to their commitment to enjoyable entertainment. After a decade, even the sheen of the Transformers films has worn off, whereas Marvel is about to have a banner year with Black Panther and Avengers: Infinity War, followed in 2019 with whatever Avengers 4 is going to be. These things are guaranteed successes, to the point that parts 3 & 4 surpassing The Avengers’ box-office haul seems inevitable. People want to see The Avengers team up with the Guardians of the Galaxy, characters even seasoned comic fans hadn’t heard off a few years ago. It’s a damn shame they don’t want to see the Justice League, but when presented with the option having guaranteed fun, or a slog with empty versions of previously more popular characters, what do you think they’re going to choose?

None of this is new information of course. The problems with the DC films are amply clear, and they’ve begun their course-corrections already with their 2017 films. But one has to wonder if the damage is already done. Ultimately, even the beloved characters and fun stories all work in service of branding. Marvel is a brand. Pixar is a brand. Fast & Furious? That’s a brand too. Star Wars is a brand, Disney is a brand, and even the Minions are a brand unto themselves at this point. But these are brands that constantly turn a profit because audiences know what to expect. Not that the next Marvel and Star Wars films shouldn’t attempt to be different (by the looks of them, Black Panther and The Last Jedi absolutely will be), but their respective labels come with the promise of spending a few hours with characters people would kill to interact with, rather than characters who might want to kill them.

The only thing that can really fix DC’s problem is an entirely new brand identity, but they don’t want to reboot their biggest success Wonder Woman either – which is why you’ll probably hear about the universe-altering soft reboot Flashpoint happening sooner rather than later. Keep the stuff that works and throw away the rest like it never happened, much like the comics they’re based on. It’s not ideal, but it seems like the only way forward.