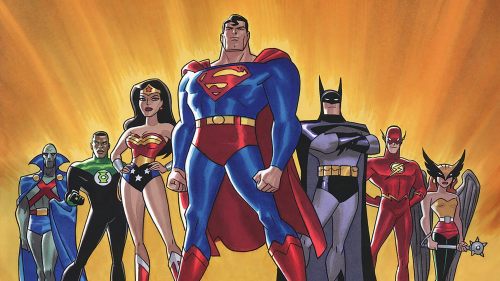

JUSTICE LEAGUE: Salvaging The DC Superhero

Justice League feels like the untangling of a disaster or three. A response to responses to both the Wonder Woman smash and the BvS slog, in turn a response to responses to Man of Steel (sorry for making the word “response” look weird). A refracted, re-Xeroxed image of a brand trying to be little more than “Not Marvel” to the point of inadvertently coming full circle to “Marvel Lite.” It’s the movie equivalent of putting a mustache, red hat and overalls on Sonic The Hedgehog before making him rescue a princess from another castle, a nonsensical decision within the world of the story that somehow carries its own allure of absurdity. It’s a course-correcting, “Please clap” retcon, reeking of desperation. A film that has no choice but to be apologia, soft-reboot and corporate panic-release all at once, to the point that it may as well have been dumped in the January wasteland. In short, it’s a mess. And yet “Please clap” I did, because it’s a mess that feels sorely needed for the DC universe.

Even before its first frame of footage, Justice League feels like a markedly different product. The whimsy of Danny Elfman’s score balances out the familiar ominousness, as the film opens with the retroactive re-tooling of WB’s dour Man of Steel. Henry Cavill’s digitally de-mustached uncanniness aside, the brief prologue acts as a mission statement, re-introducing us to Superman from a human perspective for once. A child records him on a smartphone and asks him the meaning of his iconic ‘S.’ More specifically, he asks him the question we’ve all be asking of this conception of Superman since 2013: exactly why does this symbol represent hope?

Superman responds: because it’s like a river. It comes, and it goes, but it always returns. Justice League is the attempt to force its return. Whether or not it feels earned, the hope returns regardless, though what shape it takes in the future remains to be seen.

Superman is dead and the world is without hope. The ways in which this global pessimism manifests range from the familiar (hate crimes and petty violence) to the bizarre (a cult of conspicuously dressed bank-robbers hoping to blow up the world and start over), but its most poignant element comes in the form of Martha Kent selling the family farm. Superman’s familial foundation has been sorely missing from these films – a foundation that truly makes him feel like a paragon of decency – and the opportunity to lay that foundation may be gone for good. That is until Superman comes back from the dead, his unrelenting anger playing like a more extreme version of the Snyder Superman we’ve grown used to seeing. His return to his "old" self (a version of Superman referenced in Justice League, but a version who has only existed outside the films) comes about once he spends time with the people who make him who he is, at the place he calls home. It's a simple notion, but it speaks to the simplicity of the character's foundations.

Granted, we never actually see much of the time he spends here (we don’t see much of Superman at all once he returns), but it’s a retcon that feels like the lesser of two evils, undoing the angry, brooding version of Superman by sweeping him under the rug rather than having the characters talk about change that cannot possibly feel earned. Not when you’re creating a fundamentally different character. The result is worthwhile, as Superman feels distinctly Superman, both in demeanor and in action in his mere handful of scenes. The most prominent indication of this payoff comes about during a climactic moment, as Batman begins to explain the urgency behind needing to separate the apocalyptic Mother Boxes. Before the Caped Crusader can even finish his sentence, Superman rushes off to save endangered civilians. The end of the world can wait. This Superman's first instinct is to save absolutely everyone.

Batman’s place in the film feels similarly altered. It's a distinct departure from the volatile, unstable, borderline horror-movie version of the Dark Knight seen in BvS (an interesting idea, execution aside), and while it feels oddly disconnected to see him speak of “Clark” like an old friend – they barely exchanged two sentences after Batman decided not to murder him – his new self-aware ethos revolves around his place on a team of superior beings. This Batman hurts. He’s out to risk his neck for the world, and it feels real and meaningful since he bruises and breaks. After twenty years of saving Gotham from clowns and masked maniacs, he questions whether the new world of Gods and aliens needs him at all. Must there be a Batman in a world of Avengers and Justice Leagues? Unfortunately there's no follow-through to this Bat-dilemma, other than the rest of the League (sans Superman) strangely deciding to save him from Parademons rather than helping civilians when he puts himself in harm's way. Beyond that, Batman isn't really allowed to stand out or advance his story in any way, but for one specific bit of advice:

As The Flash cowers in the face of his first ever “battle,” Batman fulfills the kind of mentor function that makes him feel distinctly like the head of the Bat-family (Batgirl, the Robins, etc.), telling the Scarlett Speedster that all he has to do is save one person. The Flash takes care of the rest, and he manages to do so while being a burst of positive energy in any scene he’s in. Ezra Miller’s Barry Allen may have the same backstory as Grant Gustin’s on The CW, but he’s much more of a loner in search of family. He’s a kid who really wants to save his dad but he has no idea how to be a hero alone, which puts him in the perfect position to become a part of the team.

Aquaman on the other hand, Jason Momoa’s distinctly surfer-bro Pacific Islander, enacts his own forms of smaller heroism while choosing to be alone. He’s been rejected by both his societies, the Atlantean and the human, setting the stage for a potentially interesting tale of biculturalism somewhere in the future. In the meantime, his temporary step towards re-joining the world comes in the form of running headfirst into certain death with people who finally accept him. He’s the kind of casually cocksure superhero that doesn't feel like he belongs in a self-serious world. The "DCEU" is a world still trying to repair itself four years in, but it's doing so by presenting audaciously entertaining characters, and this Aquaman is about as entertaining as they come. His memorable lines (perhaps the most memorable of the film) are endlessly quotable, even though they aren’t really lines at all. If anything, they're brief expressions of enthusiasm that stem organically from character’s specific zeal. Awright! My man! YEAYUH! He may not have much to offer beyond quips just yet, though Momoa’s brand of straight-to-the-point realism makes for an interesting blend with his trident and green armour, and he sets the stage for the Aquaman movie in a way that feels satisfying.

Ripe for his own solo film at some point is Victor Stone a.k.a. Cyborg, a surprise standout. An accident and botched repair leaves the bionic Football star in the unique position of having to process all human knowledge as his body grows more alien. He’s the only member with anything close to resembling a full character arc, coming to accept that his curse might be a gift that he can use for good, but his story peaks less than an hour into the movie. It’s a condensed trajectory, one that renders the rest of his scenes perfunctory from a story standpoint, but he's afforded some wildly entertaining one-on-one time with The Flash, his fellow “mistake." They partake in what might be the film’s best and weirdest sequence (a literal grave-robbing) as Ray Fisher commands Cyborg’s voice with a cool, collected cadence. Fisher's performance is designed to not stand-out, leaning towards a consistently even tone but one that never feels monotonous. He constantly withholding, fighting to stay in control of his emotions lest they cause his new defense system to lash out, and the stage actor embodying him is exact in his every delivery. Cyborg is probably only 8% human at this point, but he's 100% the kind of guy you'd want to get life advice from.

The only character that doesn’t need salvaging is Wonder Woman, whose solo movie will probably go down amongst the best in the genre. While the lens employed here is markedly different from Patty Jenkins’ solo film (for a perspective on how it feels leerier, do read Britt Hayes over at ScreenCrush), Diana stays a believer and emerges as one of the de-facto leaders of the Justice League. Though she may be wrong about Superman’s resurrection in the long run – in the short term, she’s on the money – she also gets to punch co-leader Batman in the gut for using his detective skills to be a presumptuous twat about good ol’ Steve Trevor. Batman v Superman was her return to the heroic spotlight after a century-long absence, but it’s this film that allows her the opportunity to stay there.

These are the key upsides to Justice League. They not only set up a bright future for this universe while closing the book on the joyless, boring mess it once was, but they also manifest in the form of some genuinely entertaining interpersonal dynamics. The Flash and Cyborg, the most “jokey” and serious members of the League, may as well have their own buddy movie. Aquaman cuts Batman’s gimmick down to size while still being a supportive superbro. Wonder Woman also cuts Batman down to size, but while being far less tolerant of his bullshit. She even forms Cyborg’s mirror image: he hides from the world, she hides within it, and they’re both scared to let people back in after the losses they've suffered. Superman gets in on the quipping by the time we hit the climax, putting on a face of decency and politeness while forcing Batman to match him (the result is two hilariously awkward Affleck close-ups, as he tries to sell the film's sudden turn into "aw, shucks!" sincerity), but the Man of Tomorrow also acts as an anchor to The Flash’s unstable social energy. He goes from the only character who can match The Flash’s speed in battle to matching him in friendly competition while speaking to him on his level, a dynamic we ought to see more of. Cavill works as this kind and sincere Superman, and it’s a shame it took four years for him to get here.

Of course, these character moments are but minor victories in a sea of numerous losses. Justice League is still a Frankenstein’s monster of a film, a work where every seam is apparent and jarring, and the majority of scenes could be placed in any order on their way to the underwhelming climax. It’s a culmination that certainly allows its characters to interact some more (not to mention allowing a couple of neat gags involving Superman and The Flash), but it feels distinctly low stakes, working overtime to make us care about an anonymous family (as if in response to criticisms of Man of Steel), yet failing to do so despite the time spent as they never really feel in danger. Its villain barely registers, and its plot begins to resemble both Avengers movies so much that comparisons are unavoidable, which is is especially damming given its failure to re-capture their magic.

Everyone gets an “entry moment” that doesn’t land, partially because it’s the second or third time we’ve actually seen them. Every other attempt at creating “moments” as distinct visual punctuation (a la the Avengers assembling, or even the arrival of individual characters) feels like a dangling thread. They have neither broader context, nor scene-to-scene connective tissue, nor any impact within the scenes themselves. Wonder Woman’s literal entrance through a bank wall occurs seconds after we’ve already seen her. Aquaman is introduced in extreme close-up after hovering awkwardly in the corner of a previous shot, getting his big wave-n-whiskey slow motion sequence twenty minutes later, sandwiched between far more important scenes. And perhaps most egregiously, Batman, Wonder Woman, Flash and Cyborg step off Batman’s transport one by one in a totally perfunctory sequence that lasts an eternity. Moments that could’ve had emotional or even visual impact exist nearly in isolation. They're rendered moot and awkward in the process, and they even feel like they eat into the film’s already truncated runtime. While there's fun to be had, it's entirely in the form of banter; little comes in the form of what the characters actually do.

Like I said. Marvel Lite.

To say that I liked Justice League, which I did, is a statement that comes with a thousand caveats. It’s a visually sloppy film that barely feels ready for theatres, a likely result of having to reshoot until the last minute. Hell, it even noticeably composites its heroes into the same space for simple conversations. It’s fun with an asterisk: the acknowledgment that it's the culmination of four years of a whole lot of nonsense that DC Films is still trying to undo. Sure, it’s nonsensensical in and of itself (Superman's return feels like an afterthought, despite being introduced as a foundational element), but it's nonsense that promises less nonsense in the future by setting up enjoyable characters you want to see more of. After so much disappointment, it’s a significant step up to churn out an incoherent film that isn’t also thematically offensive. These are heroes who deserve to be called heroes, even if the movie they’re in feels like background noise. As much as Justice League is a car-wreck in motion, it promises a better future amidst a messy corporate product that, admittedly, has one eye on the concept of hope at all times.

The bar has been raised ever so slightly. Let’s just hope we don’t have to settle for the bare minimum ever again. Not for characters this rich and enduring, and not from a studio that was able to make Wonder Woman.