Broad Cinema: The Documentaries Of Agnés Varda

From Alice Guy-Blaché to Ava Duvernay, women have been integral to cinema for the last 120 years. Broad Cinema is a new column that will feature women who worked on films that are playing this month at the Alamo Drafthouse. From movie stars to directors, from cinematographers to key grips, Broad Cinema will shine a spotlight on women in every level of motion picture production throughout history.

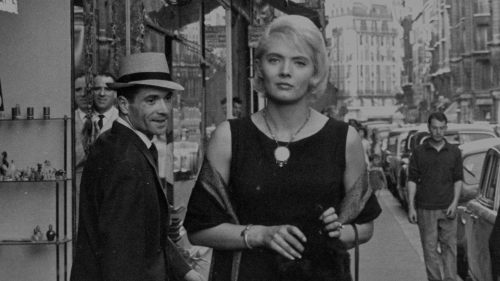

This week we are celebrating Agnès Varda’s Cleo from 5 to 7. Get your tickets here!

It is inconceivable that anyone could dive into the lush, lavish world of film without bumping into French writer, director, innovator, and master, Agnés Varda. She began her filmmaking career by coolly and confidently helming several of the medium’s most significantly progressive movements. Her first film, La Pointe Courte (1955), is almost universally recognized as the unofficial launch of the explosive French New Wave movement in the late '50s/early '60s. She cemented herself as a mother of feminist film by flipping the subject-object relationship on its head in Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962). She won the coveted Golden Lion for her exploration of homelessness, memory, and time in Vagabond (1985). She’s one of seven filmmakers to be awarded with an honorary Palme d’Or, the only woman of the seven. She’s been recognized for her lifetime achievements via the French Academy’s René Clair award, an honorary César, and, most recently, an honorary Oscar.

One of her most distinctive characteristics is her stylistic blend of fiction and non-fiction. Varda quickly became known and appreciated through her eccentric style which shattered the conventional glass ceiling that separated documentary and drama, observation and production. Despite being reductively labeled as fiction, the aforementioned films wreaked havoc on what it meant to make a film of fiction due to Varda’s documentary stylings. Likewise, Varda has never made a documentary void of fictional representation.

By the early '60s, critics and commentators began to identify the auteurs of the French New Wave in two distinct groups. The Right Bank-Cahiers group was made up of Cahiers du Cinéma film critics turned filmmakers like Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut, Eric Rohmer, and Jacques Rivette. Varda was recognized as a core member of the Left Bank group whose trinity included Chris Marker and Alain Resnais (who edited Varda’s La Pointe Courte). The Left Bank group was known for their attention to social and political issues, deliberate efforts to confuse spatial and temporal reality, philosophical and literary tone, and avant-garde methodology. Yet, Varda, and her Left Bank husband, writer/director Jacques Demy, also gleaned much from the Cahiers group through a deep friendship with actress Anna Karina and her husband, Godard. Film philosopher Gilles Deleuze would later credit the Left Bank as one of the most integral pieces in the formation of an ethical “thinking cinema”. This was one of Varda’s primary goals: to think and to think differently.

To better label her method of filmmaking, she coined the transformative term “cinécriture,” which roughly translates to “film-writing.” She used the term literarily in order to metaphysically employ her camera as the pen with which she writes her images that house so many words. The term itself reflects the distinguished, pioneering nature of Varda. Cinécriture—thinking and writing through images on a screen—grounded her approach to all filmmaking, notwithstanding the array of experimental documentaries which comprise the lion’s share of her filmography. In fact, it is her love for documentary filmmaking and her choice to synthesize it with fiction which birthed the term.

She began making documentary films at the inception of her directorial career in the '50s while she was still employed as the certified photographer of the Théatre National Populaire in Paris. Oddly enough however, it was the turn of the century that brought out her most acclaimed documentary work. Don’t be fooled, Varda’s earliest documentaries, L.A. hippie documentaries, and postmortem-Demy documentaries radiate cinematic excellence and ooze audacity, experimentation, and self-reflection, as her filmmaking philosophy echoes. Maybe it’s senectitude, or wisdom, or patience, or something else entirely, but the 21st century has somehow yielded an even more thought-full, meditative, and approachable body of Varda documentaries.

In 2000, Varda released The Gleaners and I, an 80-minute foray into the lives of people who pick up after others in France. Some glean the left behind fruits and vegetables from a yielded harvest. Some glean whatever they can from the Parisian dumpsters. Some glean in communities, others alone. Some glean out of necessity, others out of intrigue, ethical conviction, or hobby. Varda gleans with her handheld MiniDV camcorder, picking up stories, questions, and feelings from her subjects. Her narration conjures an intimate, diary-esque mood while her attempted objectivity with her subjects allows for open, measured reflection from the viewer. All the while, her intermittent explications of self, ruminations on life and death, and callbacks to her boundless career reveal a meta-layer of gleaning that Varda is knowingly participating in, as if this final stage of 21st century documentaries is her collected gleanings over time.

Her next documentary film, The Beaches of Agnés (2008), follows a similar path, this time much more exclusive to the life of Varda. Throughout the film, she explores her memory through mixed media, reflecting on her life with a characteristically charming sense of dry humor, playfulness, and authenticity whether on the topic of her husband’s death or in a conversation with a cat-avatar of Chris Marker. Varda sheds her celebrity status by swimming through her memory of banality as much as celebrity and weaves a film whose very fabric is empathy. Her decision to explore mixed media, like her decision to use a camcorder in The Gleaners and I, illuminate her dedication towards uprooting industry norms and reinforce her status as an innovator of the medium, even now at 89.

Despite declaring The Beaches of Agnes to be her last film, Varda came back with the Oscar-nominated documentary Faces Places in 2017, a collaborative film with street artist JR in which the two travel the French countryside simply meeting strangers and not-so-simply developing large scale prints of the strangers that they paste on walls and buildings. The film takes another meta-stance, this time as the lovingly-outstretched arm of Varda herself, grasping to understand, reflect, learn, and grow on the verge of turning 90. The final scene once again strips away whatever fame the viewer might still be lost in by revealing a teary-eyed Varda lost in heartbreak and disappointment after ignorant rejection from an old friend.

It is Varda’s ingrained sense of empathy with her viewers, her life-spanning career of artistic innovation and intellectual exploration, her cinematically tangible conviction towards socio-political issues, and her resounding approachability amidst it all that fortifies her astonishing career. In one light, praising her as an all-time great documentarian feels right. But in another, it feels cliché and remiss. There’s no doubt she is an all-timer, but how do we begin to categorize her? Why should we? Even her documentaries don’t fit into typical form. They are their own genre, as is she.