2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY And The Humanistic Significance Of Film Screenings

While I was waiting in the theater to watch a 70mm film screening of 2001: A Space Odyssey, I overheard a conversation. One older white man walked over to speak to a couple that he knew. The men started talking about how boring they found the new Star Wars to be - both the prequels, and the recent sequels. As to the sequels, however, both men had to admit that their grandchildren loved them.

The talk then shifted to the recent sexual assault allegations against Luc Besson. The couple brought up having enjoyed The Fifth Element, but the man dismissed the film. He brought up Atlantis and La Femme Nikita as his preferred examples of Besson’s filmmaking. Then he started talking about Besson’s cultural impact as a whole. The man said that the success of Besson’s blockbusters eliminated the difference between French and American cinema. The man sitting above the railing with his wife questioned how one filmmaker could completely erase the idiosyncrasies of France’s cinematic expression. A good question. The standing man replied that the money Besson’s films made internationally shifted the French film industry towards movies that were more akin to American blockbusters than to, say, meditative character pieces influenced by the French New Wave. When the standing man began to return to his seat, he queried, with a smile, “And maybe he’s innocent?” Referring, of course, to Besson. The man sitting with his wife replied emphatically in the negative, “With these guys it’s always true.”

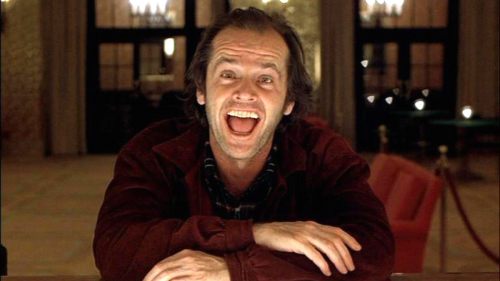

The conversation was an interesting frame for my 2001: A Space Odyssey experience. I was prepared to be angry at both of the white men who found the recent Star Wars movies, some of the most diverse of the recent blockbusters, boring. This, combined with the sudden turn in the conversation to Besson’s sexual assault reminded me of the film industry’s current post-Weinstein social climate. The way that white males with social power have been forced to deal with the consequences of their actions as knowledge of their abuse has been revealed more and more. How Kubrick himself has been, and remains, a premier example of white auteur cinematic genius, whose treatment of Shelley Duvall while he filmed The Shining was psychologically abusive and humiliating. And yet, here I was, at a screening for one of Kubrick’s movies, having decided that the artistic worth of the film, and the special conditions of this screening, overruled at least some of my own personal objections to the abuses of white auteurism.

Part of the draw for this specific screening is the effort Christopher Nolan put into this special 70mm print of the film. “Unrestored”, digitally unaltered, and shown on as big a screen with as good a sound system as possible. The experience was supposed to be a faithful recreation of the original screenings of the film’s 1968 release. Nolan compares the experience of watching film to listening to a vinyl record. He insists that in both cases, “You’re seeing more emotional information, you have a more immersive experience, a more emotional experience, you’re drawn into the film in a way that digital has a much harder time involving in these terms.” But whenever a friend who casually, digitally consumes art, asks me whether analog methods of artistic consumption actually makes a difference, I have a hard time giving a sure answer. An mp3 file, or the digital projection of a movie, is technically just as good, if not better, at the transfer and display of information than physical copies.

And yet, when I look back, the memories of my movie-watching with the strongest, most emotionally vivid recall are those films that I saw on film. I remember the haunted excitement on the faces of my brother, parents, and grandmother when we walked out of The Hateful Eight’s roadshow screening, and the uncharacteristically silent car ride home. I remember the excited, impassioned argument I had with my friends after watching a print of Spiderman 2 at The New Beverly. I remember convincing my brother to watch a screening of Red Beard with me, also at The New Beverly, at a time when he was especially stressed. We were both enthralled with Kurosawa’s remarkably humanistic masterpiece, that perfectly conflated my love for film and storytelling, and his love for medicine and social justice.

Which isn’t to say that these memories couldn’t have also been associated with digital projections. But there really is something about watching a print that changes how open your perception of a film can be. Regardless, seeing a film with a crowd on a huge screen and powerful speakers – a movie that would have played even if you hadn’t been there – is its own special social contract. Digital or film. It’s an experience simultaneously shared with others, all of whom have agreed to commit their time and energy to watch something together. But when a movie is shown through film, and I notice the small grains of the physical material the onscreen images were printed on, and the uniquely warm effervescence of the projecting light, I realize somewhere in the back of my mind that people are communicating with me. The physical is reminiscent of the human. I become even more willing to engage with the film, because the recognition that it is the result of human work and ingenuity activates my empathy and willingness to engage. And the psychological and emotional openness of my engagement makes the context of my experience more memorable.

This might be why I haven’t been able to forget the conversation I eavesdropped on before the screening itself. And why this particular screening of 2001: A Space Odyssey made me consider things I hadn’t thought of the first time I watched the film with my mom on our living room television. When I first saw the movie I was perhaps too aware that I was watching a Great Film. I thought the acting was cold but the visuals were stunning. But because I was watching the movie on my own terms, there was a bit of a conceptual distance.

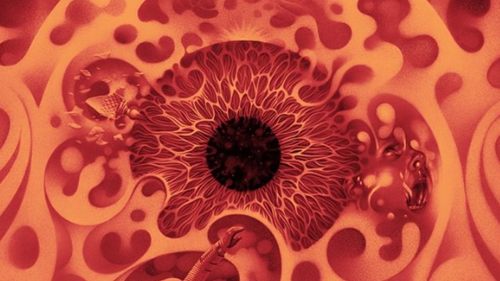

Not so at the screening. Completely at the mercy of what was unfolding in front of and around me, it became clear that what was previously perceived to be cold was really rudimentary. That between the primitive associations with the apes at the start, to the cognitive and emotional suggestions of HAL 9000, Kubrick was concerned with the basic connections of what really motivated people. This is why the actual humans seem so focused, measured, and detached, even when they talk to loved ones on monitors or become concerned with each other’s well-being. Meanwhile, the most emotional associations are with the entities that aren’t quite human. The apes at the beginning, whose wild eyes and conflict over the water hole reveals the first use of a tool to kill. And HAL 9000, the computer whose voice is so loaded with personality, and whose piercing red eye is so suggestive. The latest development of the original tool, whose deadly expression calls right back to the first murder of those primitive apes that humans consider themselves to have surpassed.

While most movies use cinematic language to express the immediate emotional relevance of a given scene, Kubrick was more interested in analyzing, pointing out connections. This is especially true with regards to how Kubrick utilized sound, which brings to mind the conceptual “counterpoint” that Akira Kurosawa discusses in his autobiography Something Like an Autobiography. His realization after watching the Soviet film The Sharpshooter, while he was filming Drunken Angel, that cinematic music could be more than just direct accompaniment. That the contrast between what is heard and what is onscreen could yield more effective cinematic expression.

Kubrick’s docking scene, scored to Strauss’ Blue Danube Waltz, is a wonderful example of this. The wide shot that shows the whole of the docking station, from the slowly landing ship, to the open rooms where various scientists and employees are all working to ensure a safe landing, would make a great establishing shot in another movie. Then they’d cut from one room to another, highlighting the efforts of the landing crew, with music to emphasize a stressful or hardworking atmosphere. Instead, that wide shot is the only shot. Kubrick has us watch as the ship slowly descends, while the men work in the rooms from a distance, and it’s all scored to the familiar, light, and elegant waltz. The sound runs counterpoint to the emotional expectations of stressfully guiding a ship to a safe landing. The music invites appreciation instead of concern, and even associates the ship’s movement to the timing of the music as a kind of dance.

The monolith – and the relentless choir of haunting voices that gives its perfectly crafted appearance an otherworldly, almost sacred prominence – suggests intelligent alien life, urging humanity on. But I’ve always wondered whether the monolith was more suggestive of something internal. An idea of perfection, maybe genetic, maybe the sum of processing the world around us, that gives way to unconscious sparks of ingenuity. The monolith seems so strange and uncanny because it refers back to us, communicates something we barely recognize about ourselves that suggests the potential for change. Like Nolan’s similar Tesseract in Interstellar, where Cooper, utilizing the tools of science but motivated by the love of his daughter, sends signals back to himself and his daughter that develops into humanity’s collective evolution.

Roger Ebert closed his Great Movie review of 2001 thoughtfully and encouragingly, “It says to us: We became men when we learned to think. Our minds have given us the tools to understand where we live and who we are. Now it is time to move on to the next step, to know that we live not on a planet but among the stars, and that we are not flesh but intelligence.” The tools we use to strengthen and expand our intelligence are varied. Not just observational and scientific tools like telescopes and calculators. There are also artistic tools like pens, paintbrushes, and cameras. Abstract and iconic tools like language, literature, and film.

And yet, watching this magnificent movie, this tool of intellectual development, on material film, reminded me that it is human, flawed, and that the path towards evolution is riddled with error and pain. I felt especially open to considerations of the dangerous legacy of Western scientific empiricism and selfish capitalistic motivation that enabled social Darwinism and justified cultural hegemony. The actresses who have been and continue to be abused in the name of “genius”, and all the people whose social representation has been stereotyped and misrepresented in the most widely circulated expressions of art and media we have. That every effort to think and create and evolve has also been adulterated by the basest of our motives and instincts.

Being mindful of these concerns is a good thing. Two or three years ago, my screening probably wouldn’t have been preluded by a conversation of sexual assault. The social, historical, and emotional contextual relevancy wouldn’t have informed the experience, and that experience would therefore be incomplete. Because if we’re going to keep putting faith into the artistic, political, and scientific institutions that will ultimately help us “evolve”, then we need to consider all the human effort – the negative and the positive, the objective and the emotional – that created them.