DR. STRANGELOVE Or: How I Learned To Stop Worrying And Embrace Toxic Masculinity

Get registered to vote if you haven't already! It only takes a moment!

***

Toxic masculinity is a term bandied about a lot, not without good reason but often without proper explanation. The sociological concept of "toxic" masculinity is not a denunciation of any and all masculinity as bad or undesirable, but is rather the labeling of widely accepted behaviors that, despite being actively encouraged and reinforced in our culture, are harmful both to the men who practice these behaviors and to the people those men interact with. As you can imagine – or realistically, you don't have to – those toxic behaviors are widespread across the half of the population assigned male at birth, conditioned to prioritize sexual dominance and to suppress emotional reactions that supposedly denote weakness. This understandably becomes a problem when the vast majority of positions of political power are held by men, propelled by the continual outward appearance of strength and either oblivious to or disincentivized to dismantle the systems that reward their toxic behavior. Now, the term "toxic masculinity" wasn't coined until the 1980s, but Stanley Kubrick demonstrated a deft understanding of the concept in his political deconstruction Dr. Strangelove.

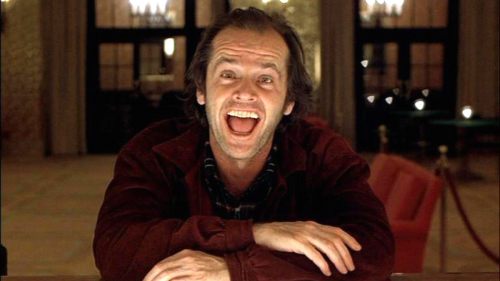

Think back on how the male leads of Kubrick's dark comedy are introduced. Major Kong (Slim Pickens) at first appears to be paying close attention to something of vital importance in the cockpit of the B-52 bomber, but the camera pulls back to show that he's intently fantasizing over a Playboy centerfold. General Buck Turgidson (George C. Scott) is introduced in a sexual relationship with his secretary, which later follows him into the War Room as he prioritizes mollifying his ticket to sexual congress over the potential threat of nuclear annihilation. And though we don't immediately learn this about Brigadier General Jack Ripper (Sterling Hayden), it is eventually revealed that his conviction that Communists have poisoned the water originated from his inability to perform in "the physical act of love." These are men who prioritize sexual performance even above their duties as military leaders, and that inability to satisfy themselves sexually gets funneled into the Cold War aggressions that eventually destroy the world.

This is because the first reaction of these men is to respond to their virile desires with violence on a massive scale. Major Kong is dedicated to the cause of dropping a bomb on their target, even at the expense of his crew and his own life as he rides the bomb down – framed as a giant phallus between his legs – to unwittingly trigger the Russian doomsday device. Turgidson is especially keen to wrap up the evening's disturbance of his sexual congress from Plan R through the most destructive means possible. He is actively excited by the possibility of launching an all-out assault on Russia, destroying ninety percent of their nuclear capabilities with projected U.S. casualties numbering "only" in the millions. Death on a massive scale is not only amenable, but it is the most efficient pathway to sexual release.

And of course, as the progenitor of this crisis, Ripper is the most explicit embodiment of masculine self-sabotage, unilaterally committing the entire world to mutual destruction because he can't accept his inability to perform sexually and seeks to blame anyone but himself. When the absurdity of his fluoridization theory is deconstructed for him, rather than own up to his delusion he opts to kill himself. Ripper is the err example of presenting masculine strength for the pure sake of it, to the point that admitting weakness even to oneself is less preferable than the destruction of literally all life.

It's notable, then, that of the nearly exclusively male cast there are three overt examples of men who aren't explicitly driven by violently manifested sexual desire, all of whom are portrayed by Peter Sellers. Lionel Mandrake, the British exchange officer stationed with Ripper, is a vision of rationality and reserve, something of a parody of English stiffness but is among the most level-headed of the characters through the implication that his military duties are worth more to him than dealing with the traumas imparted upon him during his time as a prisoner of war. This is a different form of masculine repression, but according to Kubrick it is preferable for the capability it gives Mandrake to talk down Ripper and solve the mystery that motivated the activation of Plan R.

The second of Sellers' non-toxic trio is President Merkin Muffley, a nomenclature that acts as a dated and admittedly sexist implication that the man is as effeminate as his namesake. Muffley is a consistent and firm advocate for resolving the Plan R crisis on peaceful terms, but he is also largely ineffectual, letting his generals dictate the tone of the conversation even as he denies Turgidson the pleasure of a genocidal warpath. When the Soviet ambassador (Peter Bull) is discovered to have a spy camera on his person, Muffley treats the act of espionage like a concerned parent, ostensibly in charge but without the backbone to enforce any sort of consequence for the offense. Kubrick's implication here is that Muffley's femininity is what prevents him from effectively stopping the need of his hypermasculine military to prove their nuclear virility, which creates problems in a narrative with effectively no women in it, but a more generous reading paints Muffley as yet another man who equates sex drive with social capital but does not believe himself capable of the necessary strength to counteract the aggression of the forces that ostensibly answer to him.

But it is the final of Sellers' characters, the titular Nazi scientist who advises the War Room, who demonstrates the most insidiously destructive power of toxic masculinity. Strangelove is not himself a symbol of sexual aggression, reinforced problematically by his position in a wheelchair, but he is a character who knows how to manipulate the wills of masculine aggressors to his will, feeding on ideals of procreative non-monogamy in a mineshaft survival scenario. As Turgidson and the other military leaders drool over the prospect of a paradise of fuckable women, ten females for every one of them, Dr. Strangelove is casually introducing a eugenics program into a new world order, calculating the most "desirable" of the population for breeding purposes. By thinking with their dicks, the leaders of the United States have doomed the world to a fascist resurgence among the limited group of survivors, undoing the work accomplished by a world war fought only one generation prior. As Strangelove fights with himself for control and his reformed facade crumbles, he refers to President Muffley as "mein führer" and works himself into a standing position, proclaiming that he can miraculously walk, closing out the film on absurdist display of Nazi power as the world built by those who defeated them becomes engulfed in mushroom clouds.

There is no moral center to Kubrick's bleak portrait of military hierarchy, only a powerless resignation to the reality that those in power are driven by the same toxicity as any mortal man in Western culture. Though Kubrick likely framed these issues as intrinsically masculine rather than behaviors that were the product of conditional reinforcement, he still displayed an understanding of how the culturally masculine psyche had the potential to tear the bases of government and society up by their roots. Though his prediction of fascism and global collapse did not come to pass in the Cold War, Kubrick's parable of toxic masculinity finds itself still relevant over fifty years later. The players are slightly different, the dynamics of global politics have shifted, but the most powerful men in the world are still being driven by their penises toward mutually assured destruction in the name of personal power and saving face. And maybe all we have left to do is laugh at the absurdity of it all. That shouldn't stop us from trying to save our world at the voting booth, but maybe it's worthwhile to laugh to keep ourselves from crying.