Ryan Stegman And Donny Cates’ VENOM Is A Brain-Munchingly Great Comic

Venom is out now! Get your tickets here!

FAIR WARNING: This article will contain spoilers for the first story arc of Stegman and Cates’ Venom.

Superheroes and supervillains need to be flexible if they are to survive. Take Spider-Man, for instance. He started out as an angry, bitter teenager who vowed to be better after his arrogance and callousness got someone he loved killed. In the years since Steve Ditko and Stan Lee introduced Peter Parker, he’s been everyone from a dashing college student to a good-hearted science teacher to a globetrotting adventurer who battles super crime while serving as CEO of a multinational conglomerate. The quality of these stories has ranged everywhere from amazing to dreadful. Yet, even with bleak spots like the notorious Clone Saga in his past, Peter Parker endures, as do his peers amongst comics’ long-lived costumed adventurers. New creators come around with new ideas, new stories and new interpretations of comics’ many heroes and villains. Some fall into infamy, others become shining beacons of cape comic excellence. While Spider-Man’s arch-foe/sometimes ally Venom doesn’t yet have quite same amount of history as the web-slinger himself (Venom the alien symbiote is 34 years old and Venom the human/symbiote hybrid 30 compared to Spidey’s 62 years), he’s been around long enough to have gone through his fair share of creative peaks and valleys. Wherever Venom’s self-titled film lands in his history, I’ll happily wager that his current comic will be remembered as a highlight.

Drawn by Ryan Stegman and written by Cosmic Ghost Rider’s Donny Cates, Venom is an unexpectedly poignant story about the fraught, close relationship between the alien symbiote Venom and his host, the disgraced journalist Eddie Brock. Simultaneously, it’s a slamming action extravaganza with a peppermint twist of cosmic horror. Venom’s first issue opens with Eddie and Venom awakening from a disturbing nightmare in the flophouse where they’ve holed up, both of them alarmed by Venom’s increasingly unstable, violent behavior. It ends with a giant symbiote dragon bursting out of New York’s streets, and the band of feral symbiotes Eddie and Venom had been fighting declaring in a long-dead language “God… God is coming.” Stegman and Cates’ Venom escalates quickly, of that there can be no doubt. It would be very easy for the book to spiral out of control, unbalanced by the leap from “Venom, New York’s antiheroic protector of the innocent” to “Venom, suddenly New York’s best hope against a genuine goddamn Evil Space God.” But through the six issues that make up the story arc, Stegman and Cates keep a firm hand on the wheel. As cosmic as their Venom gets (and it gets cosmic, to the point that a certain awesomely-named weapon makes an unexpected but very welcome appearance), the duo and their collaborators ground the far-out happenings with Stegman’s impeccable body language and the thoughtful contrast Cates establishes between Eddie and Venom’s searching self-doubt and Knull the Symbiote God’s depraved, implacable certainty.

Consider Stegman’s body language:

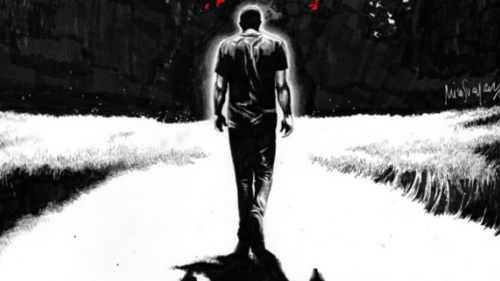

Even when he and Venom aren’t suited up, Eddie Brock is a big, powerful man. He’s a presence, fangs or no fangs. And at the start of Venom, he’s a wreck. Venom’s increasingly erratic behavior and their shared nightmares have done a number on him, even compared to his past low periods. He slouches. He lumbers, too big for the doorway of his bathroom. Picking up a bottle and taking two of what Venom calls “the quiet pills” looks exhausting. Stegman’s Eddie isn’t just worn out, he’s ragged.

Knull the Symbiote God on the other hand, walks through the world as though it exists solely for him. He’s lanky and reedy, but as long as things are going his way, he has a posture worthy of his divinity. When Knull summons Venom to examine him and finds the flophouse “…infected by… humanity”, he holds him with a mixture of tenderness and absolute contempt. Even though his triumphant return has been disrupted by Eddie, Venom and the young Spider-Man Miles Morales, Knull remains poised and in control. Whatever else may be said about him, his godhood is not in question.

Stegman also deserves laurels for the impressive feat of making Venom’s form when he’s not fused with Eddie slightly adorable. On a narrative level, it makes sense for him to be something other than his usual fanged, long-tongued self – he spends most of the story as confused and terrified of what’s happening to him as Eddie is. On a purely artistic level, Stegman took a character famous for being big, boisterous and sometimes creepy and successfully made him look like he needs a hug. That’s no mean feat.

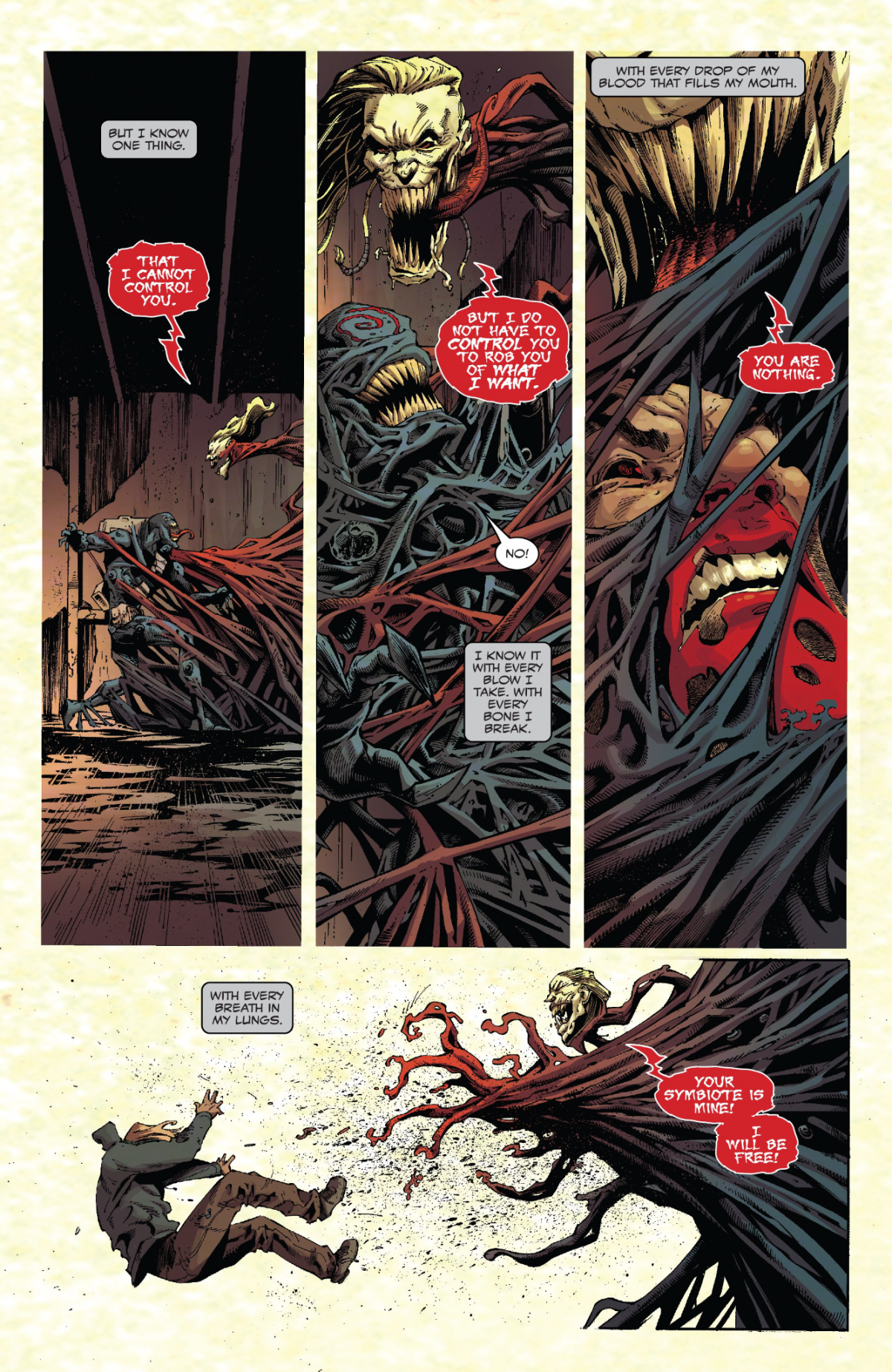

Consider Cates’ writing, in particular this excerpt from the story’s final battle:

Eddie and Venom have been through a lot together, and they both have a list of things to atone for as long as New York itself. They care deeply about one another, but their relationship has been all over the place in the years they’ve been together. They’ve worked in unison. They’ve tried to flee each other. They have abused each other and tried to atone for that abuse. There will always be tension, always be uncertainty, both for them individually and for their partnership. Recently, despite the nightmares and the erratic behavior brought on by Knull’s influence over the symbiotes, Eddie and Venom have been trying to do good, both for their own sakes and to honor the memory of Venom’s late host Flash Thompson, who helped him to heal and be better during their time together. Despite their self-inflicted wounds and the horrors that they’ve perpetrated and experienced, neither Eddie nor Venom is willing to give up on being better. They cannot get rid of their doubts and their uncertainties, but they can live with them.

By contrast, Knull is nothing but certain. Certain of his divine right to rule over existence. Certain that he alone knows what’s best for the species he created. Certain that a symbiote’s experience of anything beyond him is not knowledge to be celebrated but an infection to be burned away. It is this certainty that forms the core of both Knull’s implacable will and his Achilles’ heel. He will charge forward on his conquest, and he will not be stopped by anything, for he is a god. But despite his power and his wrath, Knull is blind to the reality that the symbiotes have outgrown him. They lived life on their own terms, experienced the connections Knull disparagingly refers to as “the light” and realized that he was not the alpha and omega he believed himself to be. He registers their turning on him as nothing more than defiance to be punished. And consequently, he underestimates Eddie, Venom, Spider-Man and others who stand against him. He doesn’t recognize that he’s being outmaneuvered until it is too late for him to do anything. And despite his plans being disrupted again and again, Knull never learns from his failures. He just dismisses them and charges forward, until he finds himself partially responsible for his own undoing. Where Eddie and Venom can accept uncertainty and doubt, Knull cannot even entertain the notion that such a thing is possible.

Venom, like Cates’ Cosmic Ghost Rider and his splendid creator-owned comics God Country (with artist Geoff Shaw) and The Ghost Fleet (with artist Daniel Warren Johnson) tells a story on a vast scale by finding and focusing on something intimate. Eddie Brock and Venom’s relationship, and their shared struggles with their doubts and troubles, drives Venom. Even as they battle a being who once waged war on all of existence, even as they sprout heavy metal bat wings and learn the secret history of the symbiotes who fought in the American War in Vietnam, Venom turns on their character development. The thrill power is real, make no mistake, but Venom is fundamentally a comic about two damaged people trying to do right and get through the next day. It’s relatable, it’s human and it’s all the more striking when put up against a malevolent, blinkered god who travels the universe in a symbiote dragon.