Sunday Reads: SUSPIRIA - Psychoanalyzing Luca Guadagnino’s Rapturous Rebirth Of A Horror Classic

Suspiria is in theaters now. Get your tickets here!

SPOILERS for Suspiria to follow.

Upon initial viewing, Suspiria is an overwhelming experience, a work of art every bit as complex and visceral as the mesmerizing production performed by Madame Blanc’s company of dancers. Every frame, every character and each narrative pirouette in Luca Guadagnino’s reimagining of Dario Argento’s horror classic is infused with significant meaning — making it near-impossible to fully comprehend without witnessing it more than once.

Those familiar with the witchy mythology of Argento’s “Three Mothers” trilogy will undoubtedly recognize some of those elements in the new Suspiria — namely, the three mothers themselves: Mother Lachrymarum (Mother of Tears), Mother Tenabrarum (Mother of Darkness), and Mother Suspiriorum (Mother of Sighs). In Guadagnino’s film, this trio serves as the spine for a narrative that eschews the central mystery of Argento’s version; almost immediately after Susie Bannion (Dakota Johnson) arrives in Berlin, the film firmly establishes that the Tanz Academy is run by a coven of witches.

The similarities between Argento and Guadagnino’s versions largely begin and end there; this Suspiria is not so much a remake, but a reimagining — or, to borrow from Madame Blanc (Tilda Swinton), a “rebirth.” Guadagnino’s film is in constant dialogue with Argento’s iteration, re-contextualizing and rebelling against its story, characters, and even its visual style. In this way, Guadagnino’s approach is itself a part of the intricate thematic fabric of Suspiria.

Rebirth and Rebellion

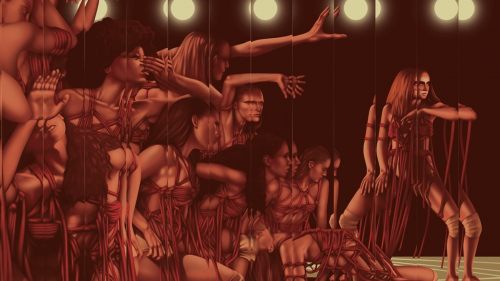

A fresh-faced Susie Bannion — her eyes bright and inquisitive, her voice the sound of a sigh — sits among her new classmates at the dance academy in Berlin as Madame Blanc calls them to attention. “I want to start work on a new piece,” says Blanc. “A piece about rebirths — the inevitable pull that they exert, and our efforts to escape them.” But this piece isn’t exactly new; it is Volk, the visceral interpretive dance Blanc created in 1948 in the wake of World War II. It is a demanding piece that requires more than any one student can possibly give, which is why Blanc enhances her most talented dancers with additional physical gifts — painfully procuring them from fellow students, who are now seen as lesser in the presence of greater talent that might put these skills to better use.

As with Volk, this Suspiria is not necessarily a new piece, but a “rebirth.” Blanc’s rumination on our relationship with this concept — “the inevitable pull that they exert and our efforts to escape them” — could aptly describe our feelings about remakes in general. But Suspiria is not a remake, nor is Volk. Both have been re-contextualized: Suspiria as a feminist work of art in dialogue with its creator(s), while Volk is being re-adapted — or rebirthed — for 1977 Berlin.

Though it exists mostly in the background, that setting is as of much importance to Suspiria as anything else. 1977 was a time of great division and emerging rebirth in Berlin, where the Wall still stood as a literal boundary between East and West. The activities of the Baader-Meinhof Group (otherwise known as the RAF, or Red Army Faction), a militant far-left collective from West Germany intent on reclaiming the nation’s history, had reached a peak in 1977. It was during this time, known as German Autumn, that David Bowie came to Berlin to record a series of albums — including the monumental Heroes — in the shadow of the Wall.

Inside the dance academy, there is a similar rebellion brewing amid the growing division between the old and new, as Madame Blanc vies to wrestle control of the school from the enigmatic and reclusive Mother Markos. Some of the instructors have come to believe that the aging Markos is abusing her power and compromising the purity of the school’s artistic vision by exploiting certain students — like Patricia Hingle (Chloe Grace Moretz), whose stories about witches and rituals are dismissed as little more than paranoid ramblings by her psychoanalyst; or the Russian dancer Olga, who openly accuses her instructors of witchcraft following Patricia’s suspicious disappearance. Olga imminently finds herself trapped in a mirrored room where her body is gruesomely contorted, beaten, and internally pulverized by an unwitting Susie — whose performance of Volk casts the damning spell.

The key point of contention among the coven is Markos’ reckless treatment of the most skilled students, conducting rituals in an attempt to appropriate their youthful bodies (and talents). But Markos’ recent efforts have resulted in repeated failures. She has been impatient, greedy, and zealous; the girls were not quite ready; it was too much, too soon. In this respect, Suspiria is, on its surface, also a film about the corporatization of art — a theme reflected through the maternal underpinning of the mentor-protege relationships between Blanc and Markos, and Blanc and Susie, and marked by its potential to be mutually beneficial…or destructive.

The Three Tildas

It seems only fitting in a film anchored by the mythology of the Three Mothers to have Tilda Swinton assume a prominent trio of narratively consequential roles — each of which represents the three structural components of the psyche as defined by Sigmund Freud: Ego, super-ego, and id. This preoccupation with trilogies both literal and figurative is apt given that Suspiria eschews the more traditional three-act structure in favor of chapters; thus, each component of these trilogies — three Tildas, three Mothers, three psychic elements — serves as an act unto itself.

There is, of course, Swinton as Madame Blanc, delivering an exquisitely eccentric rendering of the great Pina Bausch — the iconic German choreographer, teacher, and performer of modern dance. Swinton’s second role is that of Dr. Jozef Klemperer, a fictional German psychoanalyst whose arc serves to bookend Suspiria’s narrative. And last — but far from least — is Swinton’s third role (or persona): Madame Markos, the monstrously decrepit and reclusive woman who controls the Tanz Academy and its coven.

In the psychic context, Markos represents the id — the primitive part of the self that is driven primarily by instinct and impulsivity. Just as Markos operates from the shadows and remains hidden throughout much of Suspiria, so the id resides in the unconscious, where it is kept isolated from the outside world and thus unaffected by reality or that which is rational. Markos is not concerned with the consequences of her actions, nor is she deterred by the repeated failures of her rituals, for the id is driven by a zealous need to quickly satisfy every impulse, however irrational or ill-advised, all in the selfish pursuit of immediate pleasure.

Blanc, then, is the ego — the self-regulating mechanism that largely operates within the rational realm, though its functions are not always conscious. In The Ego and the Id, On Metapsychology, Freud describes the ego as:

“...that part of the id which has been modified by the direct influence of the external world. ...The ego represents what may be called reason and common sense, in contrast to the id, which contains the passions...in its relation to the id it is like a person on horseback, who has to hold in check the superior strength of the horse; with this difference, that the rider tries to do so with their own strength, while the ego uses borrowed forces.”

In the context of Freudian psychology, Madame Blanc is the functional component of the psyche, mediating between the id’s irrational desires and what it perceives as the unpleasant realities of the actual world. The ego organizes, constructs, intellectualizes, and plans; it makes calculated choices and develops a strategy based on social norms and conventions. Like the id, the ego is also preoccupied with pleasure, though its means of deriving satisfaction for the id are more practical and realistic. To this end, Blanc is the face of Tanz: Her elegance and composure obscures the greedy, infantile beast within.

That leaves Klemperer to fill the role of super-ego, which develops, per Freud, through the guidance of our parents and parental figures — which grows to include teachers, mentors, and other authority figures. The super-ego comes into being between the ages of three and five — what Freud considered to be the “phallic stage” of psychosexual development. It is apt, then, that Swinton’s male persona represents the super-ego, particularly given Freud’s description of this psychic component with regards to the intergenerational implications in his Dissection of the Psychical Personality:

“Thus a child's super-ego is in fact constructed on the model not of its parents but of its parents' super-ego; the contents which fill it are the same and it becomes the vehicle of tradition and of all the time-resisting judgments of value which have propagated themselves in this manner from generation to generation.”

It should be noted that Freud delivered this lecture in 1933 — the same year that his writings were burned by the Nazis; the same Nazis who took Klemperer’s wife away to die in a camp when he failed to evacuate her from Germany. Klemperer’s function in Suspiria is that of a stubborn society that is slow to change; it is of a passive witness who fails to take necessary action; it is also that of the super-ego — that which has internalized societal norms and cultural traditions, perhaps to its (his) own detriment.

Although much of Klemperer’s role is defined and dictated by Freud, his appearance calls to mind that of one of the psychoanalyst’s great contemporaries and former collaborators: Carl Gustav Jung. “Jung is an interesting counterpoint to what Klemperer believes,” says screenwriter David Kajganich. “He wouldn’t credit that philosophical point of view.” Still, it’s no coincidence that Suspiria opens with a scene in which one of Jung’s texts can be seen resting on a table in Klemperer’s office. “Luca and I had more conversations about Jungian and Freudian theory than we did about horror movies,” explains Kagjanich.

The Four Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious

To understand the four primary Jungian archetypes, you must first become familiar with Jung’s definition of the human psyche. Like Freud, Jung also believed the human psyche to be comprised of three primary components: Ego, personal unconscious, and collective unconscious. Although the two men overlap in their shared inclusion of and emphasis on the ego, Jung differs from Freud in that his definition of the ego is rooted in self-identity and awareness; it is the part of the conscious mind that contains our individual thoughts, memories, and emotions. In The Undiscovered Self, Jung was careful to explain that one should not confuse the self-awareness of the ego with self-understanding:

“Anyone who has any ego-consciousness at all takes it for granted that he knows himself. But the ego knows only its own contents, not the unconscious and its contents. People measure their self-knowledge by what the average person in their social environment knows of himself, but not by the real psychic facts which are for the most part hidden from them.”

The other two components in Jung’s definition of the human psyche reside in the unconscious: The personal unconscious pertains to an individual’s memories (including those that have been repressed) and ideas, while the collective unconscious is comprised of ideas and memories shared amongst the entire population. In a very basic sense, the Tanz Academy houses numerous individuals with their own memories and ideas who come together to perform a collective dance rooted in shared ideas and memories — and pain. And so we witness the personal and collective unconscious working in concert to serve the ego, be that Susie or Madame Blanc, or both.

Archetypes reside in our collective unconscious as a shared set of symbols representing various beliefs, motivations, and personalities. Because they exist and flourish within the unconscious, archetypes often emerge in dreams or as thematic elements in works of art — like films, for example. To Jung’s thinking, the number of archetypes could be limitless, and a few are depicted in Suspiria: The mother (Blanc), the child (Susie), the wise old man (Klemperer), and the trickster (Markos). But Jung placed emphasis on four archetypes in particular: Persona, self, anima or animus, and the shadow.

The persona is the assumed identity we project to the outside world: Susie, the earnest midwesterner who flees a repressed Mennonite upbringing; Madame Blanc, the eccentric and elegant dance instructor who serves as the pleasant mask of the Tanz Academy, obscuring its sinister inner workings; Klemperer, the morally upright psychoanalyst, whose kindly old face and manner distracts from the displacement of his emotional burdens. Though the persona is an idealized version of the self and thus something of a facade, it does not carry the negative connotations of fraud, for, as Friedrich Nietzsche wrote in Beyond Good and Evil: “Every profound spirit needs a mask: even more, around every profound spirit a mask is growing continually, owing to the constantly false, namely shallow interpretation of every word, every step, every sign of life he gives.”

The anima and animus represent opposing gender identities; the former is the masculine aspect of the female, while the latter is the feminine aspect of the male. Jung strongly believed that our development was hindered by social gender norms, reinforced by the collective unconscious. Though gender roles and their corresponding expectations were much more rigid in Jung’s time, these idea remain prevalent in contemporary society, where men are actively discouraged from exploring or embracing those qualities perceived as predominantly feminine. Women, meanwhile, are increasingly encourage to embrace the masculine in order to find success and achieve a sense of personal agency and power.

By casting Swinton as Klemperer (or Swinton as Lutz Ebersdorf as Klemperer), Guadagnino unites the anima with the animus to highlight the uneven distribution of power between the genders. According to Kajganich, having Klemperer as “the one male role in the film has a lot of meaning in upholding the perspective on how difficult it is for women to get power, and how often it needs to happen in these very hidden ways because society doesn’t hand that power to women the way it does to men.” And when women are able to acquire some semblance of power, he adds, “it isn’t effective.”

Living is not defined entirely by personal experience or choice; Jung believed that these archetypes in the collective unconscious are what motivate us and define our personalities - which is why Susie may have felt the strong impulse to travel to Berlin and attend the dance academy. Mother Suspiriorum is what calls her there. In a literal visual sense, she is the shadow archetype — a collection of all that is unacceptable to both outside society and our internal moral compass. This archetype contains all that is perceived as ugly or wrong: Greed, envy, hate, malice, bigotry, violent tendencies. To dig deeper into the concept of the shadow archetype is to understand that it has more in common with Freud’s definition of id — and thus Madame Markos — than with Mother Suspiriorum.

Although Jung believed that each person has a dominant archetype that drives them on a subconscious level, he also believed that an individual’s personal experiences and environment worked in combination with the archetype(s). Susie’s life back home on a Mennonite farm, cut off from much of contemporary society, with a strict, controlling mother and a repressed coming-of-age defines her journey as much as the unconscious call of the Shadow.

Thus, Susie is not only representative of the Jungian psyche model, she is its total culmination; it is only during the film’s divinely grotesque climax that she transcends self-awareness to achieve self-understanding, or what Jung called “individuation” — which brings us to the final and arguably most important of the four primary archetypes: The self. The union between the personal conscious and unconscious, the self (and the realization thereof) is the ultimate goal of individuation — an integrative process whereby an individual assimilates the various aspects of their personality to become psychically whole. Jung argued that people respond to the archetypes of the collective unconscious by repressing the qualities within themselves that do not reflect or conform to the archetype; individuation requires us to excavate these hidden and often unseemly qualities from the shadow and allow them to integrate with the ego. In the Jungian model, this is often achieved through the interpretation of dreams.

The Uncanny

Not long after arriving at the Tanz Academy, Susie begins to experience a series of surreal and oft-nightmarish dreams, depicted as a barrage of striking imagery — much of which pays homage to the artist Ana Mendieta (her estate sued Amazon Studios for copyright infringement prior to the release of Suspiria). These dreams and their haunting visuals speak to something primitive that exists within the collective unconscious, as well as Susie’s personal unconscious; it is within these dreams that she feels the pull toward Madame Blanc and the seeds of awareness regarding her true nature and purpose (and the self) are sown.

It is here that Jung and Freud collide again, as both were preoccupied with the psychology of dreams and analyzing the symbols therein. “As soon as I knew there was going to be a language of dreams,” Kajganich says, he began ruminating on the concept of the uncanny — specifically as Freud defined it: “That class of the terrifying which leads back to something long known to us, once very familiar.” The most simplistic and common example of the uncanny would be a doll, or a robot or android designed to mimic the appearance and / or movements of a human being (or a sex doll, for a more modern example). Though it appears familiar at first glance, closer examination yields the revelation that it is not quite “right”; the resultant feeling is one of eeriness or disquiet.

Another example Freud gives of the uncanny is the doppelgänger, or double. Denis Villeneuve’s Enemy offers a fine depiction of the unnerving quality of the uncanny through the exploration of the double, as does Andrzej Zulawski’s Possession. However, the latter is more thematically and visually relevant to Guadagnino’s Suspiria, specifically in how Dakota Johnson’s Susie bears an uncanny resemblance to Isabelle Adjani’s own uncanny double in that film.

The uncanny is not always sinister or disturbing in nature (see: the works of Wes Anderson), but for Kajganich and Guadagnino’s purposes, it most certainly evokes a sense of dread — both for Susie, who experiences this surreal quality through the dreams planted in her head by Blanc, and for the viewing audience, which experiences a very specific sense of terror vastly different from the tropes typically found in the horror genre. What Suspiria delivers is more akin to nightmare logic and existential dread; it is more grounded in reality — and thus, more relatable — than its mystical elements would suggest.

Feminist Confrontation

Perhaps the most identifiable — and socially relevant — component of Suspiria is its feminist angle. Guadagnino and Kajganich craft a perspective that is almost entirely feminine, including the casting of a woman in the single prominent male (or “anti-male”) role. The only other men present in the film are two nameless detectives who visit the academy to investigate Patricia’s disappearance. Upon their arrival, a few of the instructors take the detectives to a private room, where they are bewitched into a hypnotic state of submission, partially disrobed, and openly mocked while the women poke and prod at their genitals.

Late in the film, after tricking Klemperer into returning to the academy via a cruel illusion, Miss Vendegast makes a simple remark that holds immense thematic significance: “Women tell you the truth and you tell them they’re delusional” — a statement that is as much about Klemperer’s wife, Anke, as it is about his interactions with Patricia Hingle, whose pleas for help and descriptions of witches and rituals he dismissed as nothing more than paranoid delusions.

It is around this time in Suspiria that Sara makes her way through the passageways hidden within the walls of the school, where she stumbles upon Patricia and Olga — their naked bodies mangled and deformed, contorted into inhuman shapes while their skin remains unbroken. Most horrific of all, they are still conscious and breathing. Here, beneath the school, Patricia and Olga have become the shadow — that which is ugly and repressed and does not conform to the ideal archetype. They have been discarded like waste, their talents rendered useless by their refusal (or inability) to assimilate. It is particularly notable that we never see Patricia or Olga bleed out; their wounds are wholly internal, their pain internalized and unseen. And so Miss Vendegast’s remark to Klemperer takes on another dimension, as does his role as “witness” to the hideous black sabbath sequence that serves as the film’s climax.

It is as if the traumas experienced by Patricia and Olga (and to another degree, Anke) are not real unless they are made literal and tangible — they must be seen, or witnessed, in order to be believed. The aggressive, violent ritual at the heart of the film’s climax serves as the ultimate confrontation: A bloody piece of theatre that forces Klemperer to reckon with the ugly truths he has so willfully ignored.

During this climactic ritual, the coven gives Klemperer a designation that is more an act of poetic justice than one of revenge: Witness. “It’s not enough to say that someone is a witness,” explains Kajganich. “Either someone is an active witness, meaning they will do something about what they see, or they are a passive witness” — someone who sees acts of atrocity being committed but does nothing to intervene. This position is familiar to Klemperer, who did little to prevent his wife’s presumed capture and death. Now, confronted by the possibility of further atrocities being committed within his view, Klemperer is once again presented with the opportunity to become an active witness; but again, he ignores every sign until it is too late.

“What’s so upsetting about that ritual is that he’s rendered a passive witness,” says Kajganich. “He knows when he walks out of that building if he were to go to the police, he will be misunderstood, mistrusted, even ridiculed” — not unlike his treatment of Patricia and his perception of her as someone who is not completely in her right mind. It’s a turn of events that could be perceived as upsetting, certainly, though in the thematic context, it only seems fitting; it is, in Kajganich’s estimation, a “huge act of disempowerment.”

From a female perspective, it feels righteous — even more so when Susie arrives and commences her “individuation,” the full realizing of the self that culminates with the declaration, “I am She.”

Once Susie has exposed Markos as a fraud, she expels the coven’s hideous id (along with those who reinforced its corrupting impulses) and begins the process of integration — starting with the release of Patricia, Olga, and now Sara from their torturous limbo and into the peace of death. By cutting their bodies open, Susie puts their trauma on full display, and thus Klemperer has finally bore witness to the brutal truths he has ignored as they are made plain for him to see.

But this act of disembowelment is more than mere release from the pain of living; it is, in the context of Jung, a release of the repressed attributes from the shadow, freeing those flaws which have been forcibly hidden to integrate with the psychic whole: Mother Suspiriorum, Mother of Sighs.

_1200_750_81_s.jpg)

Punishment

In “Levana and Our Ladies of Sorrow” from the Suspiria de Profundis, from which Argento originally derived the mythology of the Three Mothers, Thomas De Quincey wrote of the Mother of Sighs:

“This sister is the visitor of the Pariah, of the Jew, of the bondsman to the oar in the Mediterranean galleys; and of the English criminal in Norfolk Island, blotted out from the books of remembrance in sweet far-off England; of the baffled penitent reverting his eyes for ever upon a solitary grave, which to him seems the altar overthrown of some past and bloody sacrifice, on which altar no oblations can now be availing, whether towards pardon that he might implore, or towards reparation that he might attempt.”

In Freud’s essay, the uncanny was psychically intertwined with enucleation, or having one’s eyes forcibly removed. This fear of losing one’s sight is directly related to what he called “castration fear” — not the literal removal of one’s testicles, but a symbolic emasculation in which previously repressed ideas from infancy arise from their hidden depths. From this, the uncanny emerges.

It is important to keep both De Quincey’s essay and Freud’s definition of the uncanny in mind when contemplating the finale of Suspiria. Susie, now fully-realized as the Mother of Sighs, pays a visit to Klemperer and tells him what really happened to his wife, Anke: She was apprehended by the Nazis during her attempt to flee Berlin and taken to the Theresienstadt concentration camp. Though only there for a short time, she befriended a couple of women, and they were with Anke when she froze to death. Anke did not die alone, and, Susie insists, she died knowing she was loved; her final thoughts were of her favorite memory of her relationship with Klemperer.

Upon completing this story, Susie touches Klemperer’s arm and sends him into a violent seizure. When he awakens, he has lost all of his memories (or his sight, so to speak) entirely. It is not an act of revenge, nor is it a gift. What Susie performs in this moment is a figurative castration; a benevolent act of punishment. The truth is neither good nor bad. It is both. It is all things. It is She. And it will set you free.