Collins’ Crypt: CANDYMAN Made A Good Story Better

There isn't a lot about Candyman that's "conventional" for a horror movie: its villain doesn't really show up for a good 45 minutes, the majority of its death scenes occur off-screen, etc. But about twenty minutes in we are treated to one of the standard cheap scares: a dog suddenly popping up and barking REALLY LOUD, frightening our protagonist and presumably giving the audience a similar jump, tiding them over until a proper one comes along later. And it's not like it's a major plot point that she's afraid of dogs or anything like that, so it seems like it might be the sort of easily implemented thing a producer suggested: "Hey, it's been too long since there was a scare - have that dog bark at her!" But here's the funny thing: it's actually directly taken from Clive Barker's source material:

A shadow moved across the room, momentarily blocking her view. She stepped back from the window, startled, not certain of what she'd seen. Perhaps merely her own shadow, cast through the window? But then she hadn't moved; it had.

She approached the window again, more cautiously. The air vibrated; she could hear a muted whine from somewhere, though she couldn't be certain whether it came from inside or out. Again, she put her face to the rough boards, and suddenly, something leapt at the window. This time she let out a cry. There was a scrabbling sound from within, as nails raked the wood.

A dog! And a big one to have jumped so high.

'Stupid,' she told herself aloud.

While there have been plenty of "original" dog or cat scares in untold numbers of horror movies, the one in Candyman is simply a case of the filmmakers preserving the original vision of the story's creator. Indeed, when writer/director Bernard Rose set about adapting Barker's story - which was titled "The Forbidden" and included in the 5th volume of Books of Blood (retitled In The Flesh in the US) - he left very little out of it. Even minor characters like the pretentious Purcell (played by Michael Culkin) are actually from "The Forbidden", as are smaller details like the razorblade-laced candy Helen finds, and the sentiment that it is "better to die" than to be castrated, like the young victim in the restroom. As Rose explained during a post-screening Q&A last week to celebrate the film's new restoration (moderated by yours truly), it's usually better to adapt a short story, because you get to add to it, rather than take away from it as you have to with a novel.

Adding material was a given here: the story is less than 60 pages long, unlike the 100+ pages of previous Barker stories that were adapted (and by the author himself, for Hellraiser and Nightbreed, based on Hellbound Heart and "Cabal", respectively). As written it would probably barely hit the average length of a Masters of Horror episode, let alone a wide release feature. But what's crazy about the film is how seamlessly Rose's inventions work within the context of what is otherwise a pretty faithful adaptation; yes he changed the location (from London to Chicago, but retaining the central tenement setting) and Candyman's appearance, but if you were to flip to any random page of "The Forbidden" and skim it, you'll likely recognize it as having a film counterpart. So it's almost kind of jarring to read the story if you're familiar with the film and discover how much of it *isn't* there, as nearly everything he added felt organic as opposed to shoehorned in to pad out the runtime.

For starters, the whole idea of saying Candyman's name five times in the mirror (a la "Bloody Mary") is nowhere to be found in the story. The Candyman character functions in the same way: a boogeyman that stalks a low-income tenement, gaining power through the whispered stories about him (power that will be lost if someone like Helen were to prove/disprove his existence), but there's nothing about mirrors, and his backstory (the son of a slave, killed for having an affair with a white woman) is totally invented by Rose as well - the story offers no insight to his origins. But that doesn't mean he's a totally different character, as most of his dialogue is the same: "Sweets to the sweets", "What is blood if not for shedding", "Be my victim"... if you've tried to imitate Tony Todd's formidable voice saying something from this film, chances are they were from the source. And yes, he does have an open chest cavity filled with bees, despite the other changes to his appearance.

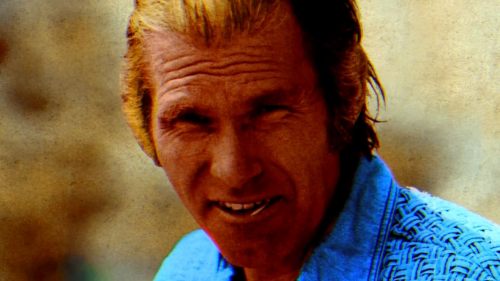

In fact, reading the story now it's almost impossible to imagine a filmed version of the character as described, as Todd has become so iconic in the role - to the extent that if a filmmaker were to say "Hey I'm going to remake Candyman but this time we will depict the character the way Clive Barker described it!" he'd probably be met with nothing but derision. Barker's prose described the character as "bright to the point of gaudiness"; he was a white man with jaundice, long strands of hair, and a patchwork outfit that Helen thought made him look rather ridiculous. Of course, there is nothing about Tony Todd's appearance that would inspire that sort of opinion, and while silly can look scary when done right (see: It) it's difficult to believe any filmmaker would opt for a more "faithful" depiction of the character over one that audiences responded to. Some comic fans may never get it through their heads that changing things for a movie adaptation isn't the end of the world, but every horror fan I've ever spoken to agrees that the film version of the character is the superior one.

As for the setting, there's more of a possibility there. The 1995 sequel Farewell to the Flesh is fine (if inessential) and I have no defense at all for the third film (Day of the Dead), but one thing I do like about the three films is that each one gave Candyman a new city - and its respective culture - as a backdrop (New Orleans and East Los Angeles, respectively), so if they wanted to "bring him home" to London I could see myself being intrigued by that. However, I think I'd save that approach for a traditional remake; Jordan Peele and Nia DaCosta are planning to set their upcoming sequel at Cabrini-Green, which has come a long way since the original film was set (and partially shot) there. Back then, you wouldn't want to go anywhere near the area; just three days before the film opened in October of 1992, a seven-year-old boy who lived in one of the Cabrini-Green buildings was shot to death on his way to school by a sniper that was aiming at a nearby group of teens (assuming some were in a rival gang), and police would often neglect to respond to other crimes out of fear of their own safety. But that's no longer the situation there - the tenements are gone and the area has become gentrified, something I'm sure both Peele and DaCosta have things to say about, while also reviving a character that's been dormant for far too long. So returning there for their followup makes perfect sense, and serves both masters: it'll have a direct tie to the best/most popular installment, while also using nearly thirty years of changes to keep it from feeling like a retread.

And then there's the ending, which might be the only change one could mount a reasonable argument against. Both end in a bonfire, but the way it's depicted in the story, Helen is kind of goaded into being trapped in it as kind of a Wicker Man-style sacrifice, with Anne-Marie (the character played by Vanessa Williams in the movie) putting her baby's corpse in the fire knowing Helen would try to retrieve it, essentially delivering her to Candyman in return for their own safety. In the film, Helen goes in there to rescue the baby and succeeds, redeeming herself to Anne-Marie (who believes her to be the baby's kidnapper/possible murderer; there's no such accusation in the original text) but dying from the burns she suffered to do so. It's probably the riskiest revision, since "we changed the ending" is usually not a good sign, but I prefer the film's conclusion; silly notion of the baby still being alive after a month aside (did Candyman change diapers?), the story's version of Helen lacked any real connection to those characters the way she does in the film, making her journey less interesting. Perhaps it's a bit of a cliche to have a third act revolving around the hero trying to prove their innocence by going after the REAL villain, but it's an improvement on simply wandering around the tenements until Candyman appears, as she does in the story.

Long story short, if Rose had made a word for word adaptation of "The Forbidden", we probably wouldn't be talking about it all that much today (we certainly wouldn't have a recent Oscar winner mounting a sequel). I'm sure somewhere there's a Clive Barker stan who stormed out of the theater when he saw that things had been modified, but such folks are thankfully rare (or at least, quiet). And even if you do feel the story was superior, I hope you'd agree that it's clear Rose (who had Barker's blessing, it should be noted) didn't just change things for the sake of changing them - he took Barker's story and expanded on it, modifying this or that as necessary while retaining the tone and point of the text. Sometimes a filmmaker will use a short story as a springboard, or essentially write a prequel for the first two acts that leads into the original story (the Corman/Price/Poe films are a good example), but Rose treated the story as a sort of tree trunk, using it to flesh out and expand on what was already there while more or less telling the same start-to-finish story: that of a woman named Helen who stumbles upon a terrifying urban legend while researching her thesis, and ultimately becomes his latest victim. It's a pretty good story that became a really good film, and in my opinion is a textbook example of how to go about doing this sort of thing. With or without the dog scare.