SUPERMAN At 40

Deconstructing the legacy of Richard Donner’s Superman is a deceptively formidable challenge. Certainly the 1978 film marked the first time that superheroes were taken seriously not just by filmmakers, but by the mainstream public. And the ideals vividly brought to life by Christopher Reeve in the title role set a standard for a sort of purity and goodness - but not innocence - that feels even more desperately needed today than they were at the tail end of the Watergate era.

But it’s also a film inextricably linked to the upbringing and influence of every comic-loving kid of a certain generation. And the cinematic legacy of the character has spanned multiple iterations, and interpretations, both reflecting the appetites of their audiences and the various time periods in which those stories were told. At 40, Superman is a throwback to a bygone era, an undeniable product of its time, and a timeless portrait of an iconic character. Its anecdotal impact on fans (including those it created) remains as relevant today as the sea change it prompted in popular culture. All of these and many more reasons are why it instantly became a classic, and continues to endure today as an essential work not just of superhero storytelling, but cinematic mythmaking.

My earliest memories of the film were from its TV broadcasts, and more specifically, my earliest recognition of the way that films in general were transferred to the small screen. Shot in 2.35:1 aspect ratio, the film was by necessity panned and scanned for television, which meant that shots where there were reel changes featured this additional “camera” movement, across the plane of the frame as opposed to across the scene itself, that I found both fascinating and confusing. (It took several more years before I figured out or more likely was taught that this was because the transitional shots often featured a different part of the frame for the audiences to focus upon, but on the small screen there simply wasn’t enough room for both.)

The opening scene of the film feels like a literal introduction between audiences and comic books, starting with a shot of a curtain that draws back to reveal Action Comics #1, and quickly moves into the frame for what was then and is now one of the best, most thrilling title sequences ever conceived. The names of the actors and filmmakers leap off of the screen, written in light - a hint at the transcendent power of this hero’s journey. (That Bryan Singer employed so many of these tricks for his 2006 film Superman Returns was a testament to the initially rhapsodic reactions to the film - meaning, the excitement of longtime fans who were after a long delay watching a Superman movie that not only respected the character’s legacy but had the discipline, and quite frankly, the money, to push it forward in a modern way.)

The iconography of the film hangs brightly in moviegoers’ minds even today, and not just because he was at that time the only superhero on screen. The vivid, elegant color palette of the film and Donner’s exquisite, clear-eyed direction offers something memorable in every location and scene, from the striking contrasts of Krypton to the gold-hued pastoral plains of Smallville to the bustling streets of Metropolis. General Zod’s trial feels massive and intimate simultaneously. There’s something heartbreaking about the distance not just between Clark and Jonathan Kent as his father succumbs to a heart attack, but between them and the audience, forced to watch a loss that no superpower could prevent. When Clark rescues himself and Lois Lane under the guise of flailing like a coward, he pauses afterward - not so much self-satisfactorily, but with bemusement - glancing at the bullet he stopped. Even their romantic interlude in the clouds, a subject of frequent derision even among fans, oozes with a hazy magic that feels just out of reach but undeniably palpable.

The murderer’s row of talent behind the camera was legendary - even at the time. Donner was coming off of The Omen, an enormous box office hit. The screenwriting team responsible for its story included at different stages Mario Puzo (The Godfather), David Newman and Robert Benton (Bonnie and Clyde), and an uncredited Tom Mankewicz (every Bond movie from Diamonds are Forever to Moonraker). Cinematographer Geoffrey Unsworth worked with Emeric Powell and Michael Pressburger before handling photography on 2001: A Space Odyssey. Production designer John Barry’s previous credit was Star Wars. And John Williams, also coming from Lucas’ galaxy far, far away, did this score, one for Spielberg’s Close Encounters, and the music for Jaws 2 all within the same year.

Warner Brothers’ approach to creating the film was further unprecedented at the time. In an effort to shore up the film’s credibility, they hired Marlon Brando to play Jor-El, Superman’s father, at a staggering cost of $3.7 million plus a gross percentage that would earn him approximately $19 million for two weeks' work. The finished script ran 550 pages, and was developed with the intention of shooting the character’s origin story and a sequel back to back. The casting process for the title character involved a look at almost every leading man and movie star of the time period, before Donner settled on Reeve, who astonishingly was only 24 at the time he took the role and largely an unknown. The studio also reportedly spent $2 million alone in flying tests, just trying to get the look right when Superman soared through the air. Its eventual $55 million budget was one of the highest ever spent at the time production was underway.

Despite Brando’s well-documented indifference to the role, much less preparing adequately for it, the performance he gives resonates with precisely the sort of gravitas that made his hiring worthwhile - especially in key early scenes when there’s much exposition. Similarly, Hackman’s initial reluctance to take the role of Lex Luthor also offered ultimately unfounded concerns for the Oscar winner: he is hilarious, ruthless and mesmerizingly sociopathic as the super villain, especially opposite Valerie Perrine’s tender, conciliatory Miss Teschmacher and Ned Beatty’s hysterically buffoonish henchman, Otis. And Margot Kidder’s Lois Lane instantly became a feminist icon for audiences around the world as the fearless, cocksure reporter who repeatedly gets herself into one spot of trouble after the next.

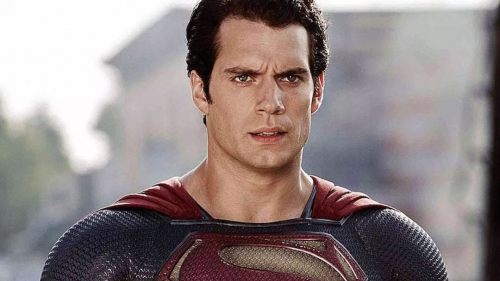

Those familiar with the film’s history know that the end of the sequel is where Superman was to “turn back time,” but Donner got booted off of Part II before it could be finished and was replaced by A Hard Day’s Night director Richard Lester. But his impact on the character and his cinematic universe had already metastasized in the best possible way, with enormous help from Reeve’s wholesome, resolute presence in the Kryptonian’s boots. It’s Reeve’s portrayal that has defined the character for decades, and it’s a visual legacy created with his director that every actor since has had to try and live down, or live up to.

In retrospect, and given the lineage of so many superheroes who were subsequently brought to life on the big screen, there’s something appealingly quaint about the tagline “you will believe a man can fly,” but what the film does, uniquely and to this day, is make you believe in and care as much about the man as the things that he can do. Which is why after eight follow-ups, 40 years and an expansive cinematic universe based on him and a host of and other DC characters, Superman’s ultimate legacy is in advancing the idea that comic characters and their stories not only could be taken seriously, but deserve to be.