JUSTICE LEAGUE And The DCAU – A Glorious Superhero Story For Everyone

Aquaman arrives in theaters this week. Those who’ve enjoyed it are describing it as a big, bold gloriously goofy adventure. It is, to quote an eloquent friend, “Wet Thor.” With Jason Momoa, Amber Heard, Patrick Wilson and his dubiously blonde hair bringing the DC universe to the screen for the holidays, I decided to take the opportunity to revisit a bit of Justice League, the 2001-2006 series (counting its successor series Justice League Unlimited) – in particular the two-part Aquaman-centric story “The Enemy Below.”

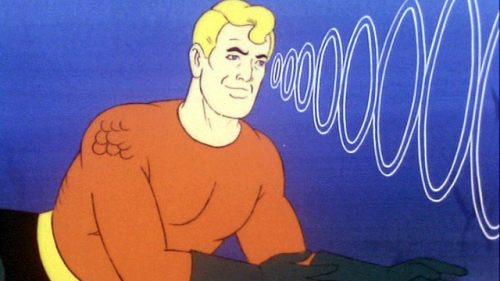

There’s a lot to love about Justice League. It creates an impressively coherent world from both the DC Animated Universe (DCAU for short) cartoons before it and the decades of comic stories from which its creative team would draw inspiration. Its character and mechanical designs are clean, clear and iconic, and they are so without sacrificing personality or, particularly in the Unlimited era, the vast range of costume styles and general looks. Visually, it’s a show that has room for both an eccentric detective who wears a mask that makes him look like he has no face and an ancient sorcerer who battles cosmic abominations. Narratively, its stories could include everything from Superman facing the evil capital-G God Darkseid for the fate of humanity to Batman singing in order to free his crush Wonder Woman from a curse. It’s a darn fine show, a splendid capstone to the creative endeavor that began with Batman: The Animated Series. And its quality has earned it lasting love. Even now, a full twelve years since the end of Unlimited, the DCAU and its interpretations of the Justice League remain touchstones for discussing DC and its characters as a whole. If I were to isolate a particular reason why the DCAU endures amidst its many virtues, I’d say that it would be the project’s commitment to telling stories for everyone. Using “The Enemy Below” as an example, I’d like to lay out what I mean by that and how the DCAU did it.

First, a quick summary of “The Enemy Below.” Aquaman, the King of Atlantis, sinks a nuclear submarine for intruding on Atlantean territorial waters. The Justice League arrive to save the crew, and after a brief clash with the Atlantean forces, are allowed to do so while leaving the wrecked sub behind. Superman persuades Aquaman to settle his disputes with the land-based governments of the world at the DCAU’s equivalent of the UN. Wishing to create a world where his young son will be able to grow up happy and healthy, Aquaman takes Superman’s advice – but his methods are heavy handed, and upon issuing a “get out of the oceans and never come back” ultimatum to humanity, he’s promptly attacked by an assassin. The League save his life, and through their investigations discover that the assassin was paid by a faction of Atlantean war hawks, led by Aquaman’s own half-brother Orm. The hawks, tired of Aquaman’s caution, aim to use a doomsday weapon meant as a deterrent to end humanity. Orm captures his brother and kidnaps his baby nephew, leaving them in an undersea volcano deathtrap and ensuring the security of his kingship. Unable to escape from Orm’s trap in time to save his son, Aquaman takes the Alexandrian solution and CUTS OFF HIS OWN HAND, allowing him to rescue his son. Reunited with the Justice League, Aquaman REPLACES HIS AMPUTATED HAND WITH A GOSH-DARN HARPOON. Aided by the League, he halts the doomsday weapon, strikes down Orm and thereafter cautiously begins bringing Atlantis into the global community – check out a clip from the climax below:

“The Enemy Below” turns on geopolitical conflict and familial strife, and its major action climax is derived in part from a horrifying potential endgame to deterrence theory. That’s a lot for any sort of story, never mind a superhero action cartoon whose primary audience is going to be fairly young. But, in “The Enemy Below” and elsewhere, Justice League pulls it off. Much like series developer Bruce Timm’s character designs, which streamline the look while preserving and even elevating the feel of their characters, Justice League tells its tales big and bold, and uses the quiet moments in between the grand set pieces to add shading and nuance. Aquaman’s arrogant ultimatum to the world leaders and their aghast responses makes subjects as thorny as diplomacy and national conflict easy to understand without robbing them of their weight, even in a fantastical setting. When Aquaman’s hardline policies are contrasted with his private warmth towards his family and his anxiety about building a good world for his kid to grow up in, moral complexity and the challenge of right action become easily understandable. “This person and the world in which he lives are complex, as are the actions he takes.” Justice League says this simply and without condescension, thereby allowing for both the youngest in the audience to grasp the story and for older viewers to dig into the heaviness.

That smart, thoughtful storytelling extends to the action, be it a super-heroic fight scene or the crucial moment where Aquaman rescues his son. Rather than wallow in trauma, precisely enough is shown to make clear what happened, creating space for grand action – like Aquaman smashing a treacherous Atlantean speeder bike squadron with the help of an Orca. The action has stakes, consequences, thrills. It gets intense, but never becomes the sole purpose for the show’s existence. It has space for both Superman talking down Aquaman from military retaliation and Superman disarming an Atlantean warship by ripping off its weapons. Justice League’s creative team, in other words, made a program that invites a whole wide audience to its table, one that offers something for all of them.