Which 2019 Best Adapted Screenplay Nominee Is The Best Adaptation?

Alright, Comments Section, I’m coming right out ahead of you on this one: No, faithfulness to source material is not the ultimate measure of an adapted screenplay’s worth or the quality of the film upon which it is based. That’s not true, it has never been true, and it is 100% not the point of this article.

The point, my friends, is fun.

See, I love seeing how stories evolve across iterations and mediums. Sometimes these stories are updated to be more amenable to the time of the adaptation. Other times, the difference between print media and visual media necessitates transformative changes to the original work, and occasionally those changes aren’t necessary but have been made anyway. Adaptation is a strange and fascinating enterprise through which screenwriters place their own stamp of originality upon previously created works, making any adaptation a bizarre hybrid of original thought and foundational loyalty that can develop into any number of permutations.

As one who is fascinated by stories and the ways in which we interact with them, charting the evolution of adaptations is something I take legitimate joy in, and the Academy Awards’ distinction between adapted and original screenplays gives me just the excuse to develop my own (admittedly idiosyncratic but not completely arbitrary) rankings of what constitutes the most faithful interpretation of a film’s source material. This doesn’t necessarily mean I think the Number 1 answer is the best film on this list – though this year that did turn out to be the case – but it does provide some insight into why these films are so well received in relation to their origins.

So enough with my pontificating: here are the five 2019 Academy Award nominees for Best Adapted Screenplay, ranked by their faithfulness to their source material.

5. A Star Is Born

A Star Is Born is a strange entry on this list because it’s not an adaptation from another medium, but rather a remake of a remake of a remake of a film from 1937, and the ways in which the story has been updated and morphed through time and the perspectives of the filmmakers in the intervening eight decades is reflective not of the original intent of the story but of the ways in which we expect this story’s delivery have changed. The 2018 version follows a lot of the same basic beats as the original, with a young woman attaining stardom in conjunction with a relationship to an older man in their career whose own stardom is on the decline, but as with the 1976 version, Bradley Cooper’s take shifts the story to one about musical stardom rather than the original’s satirical take on Hollywood star persona craftsmanship.

One might say that the straight-sold, character-driven approach of Cooper’s version is the biggest departure from the original’s tone, but I would argue that the bigger shift lies in who the films frame as their protagonists. The 1937 version unquestionably positions Janet Gaynor (as rising starlet Vicki Lester) as the audience point-of-view character, and it’s through her rise that we experience both hers and her male partner’s tragedies. The 2018 version, though, positions Bradley Cooper’s Jackson Maine as the protagonist, focusing on his internal struggles arguably to the point of sidelining Lady Gaga’s titular star. Though the latest iteration of A Star Is Born borrows the basic narrative and a few key beats from the original version, it’s a radical transformation informed by intervening versions and the particular emphasis of Bradley Cooper’s self-direction as a tragic figure, making it the least faithful reinterpretation on this list.

4. The Ballad of Buster Scruggs

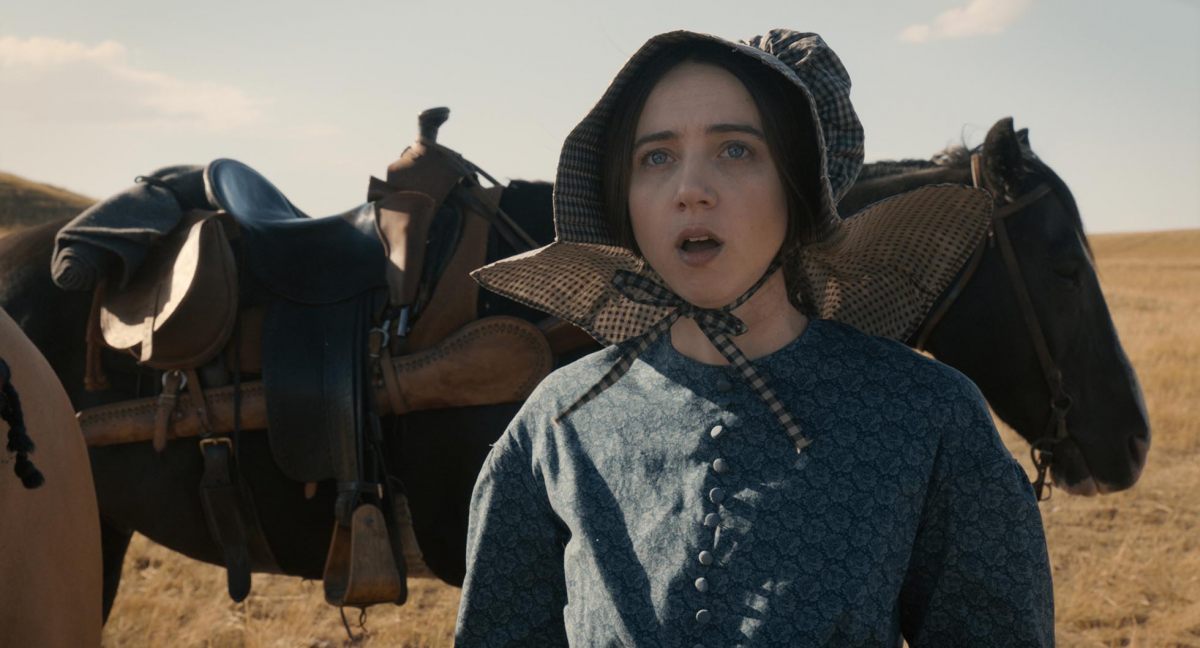

It’s something of a cheat for The Ballad of Buster Scruggs to find itself among the nominations for Best Adapted Screenplay, as four of the anthology’s six stories are completely original works by Joel and Ethan Coen, meaning that a full two-thirds of the film is not an adaptation. The first of the adapted works, “All Gold Canyon,” is actually a strikingly faithful telling of a short story by Jack London, so much so that reading London’s story feels a lot like it was written with the Coens and star Tom Waits in mind. The second adaptation, though, “The Girl Who Got Rattled” is a pretty loose expansion of a short story by Stewart Edward White. Though the climax largely plays out the same way in both versions, the primary focus of the short story is on the tragic end of its female character through nihilistic circumstance, whereas the Coen Brothers version goes to great lengths to invest that character with pathos and backstory and aspirations from the future that are absent from the original text. Were it not for the severe faithfulness of “All Gold Canyon,” this would be an easy shoe-in for the bottom of the list for the liberties the Academy is even taking with the idea of adaptation, but by my measure one entirely faithful rendering of a source text is enough to bump this up a level.

3. BlacKkKlansman

I’ve already written about BlacKkKlansman’s roots as an adaptation in some detail, but in the broad strokes it is not a terribly accurate representation of the events depicted in Ron Stallworth’s memoir, the subtly differently-titled Black Klansman. At their cores, both stories are depictions of Ron Stallworth’s incredible infiltration into the Colorado Springs chapter of the Ku Klux Klan, though Stallworth’s telling is much more procedural and reportative than Spike Lee’s interpretation. Lee inserts characters in Stallworth’s story to highlight points that he wishes to make about America’s relationship to white supremacy in our institutions, our relationships to one another and to the media which we consume, but these thematic elements are largely absent from Stallworth’s “you won’t believe this” take on the events of his own life. In short, this means that BlacKkKlansman is largely loyal to the main event it claims to portray, but it’s also extremely additive in plot structure and character beats for the sake of creating a three act structure that effectively communicates the themes Spike Lee wants to hammer home. This makes the film quite good, probably quite a bit better than a straight retelling of Stallworth’s anti-climactic remembrances would be, but it doesn’t make it a very faithful adaptation.

2. Can You Ever Forgive Me?

Can You Ever Forgive Me? is also a strange creature in terms of additive content, but mostly for the very blunt reason that Lee Israel’s memoir is a very compact, understated, and almost unreliably sparse recounting of events. The book barely skids past the 125 page mark, and a lot of that content is taken up with reproductions of the forged letters that serve as the basis for Israel’s descent into con artistry. You get a sense of her ego and the desperation of her living situation, but what you don’t get is a great sense of character or even a lot of retelling of events that would make for interesting scenes to portray on-screen. I think this is why Can You Ever Forgive Me? as a film is so heavily invested in being a character study of Lee Israel herself, standing at a distance that Israel cannot attain in order to get a better grasp on this embittered, acerbic person who engaged in a crime spree she considered largely victimless. However, I would say that this makes for a more faithful adaptation than, say, BlacKkKlansman because the point of the expanded content is to further explore the themes and psychology of Lee Israel’s interpretation of events, rather than to graft on thematic and narrative weight to an otherwise slight story. It’s still a film full of supposition and dramatic license, particularly as it pertains to Israel’s and her partner-in-crime Jack Hock’s antagonistic friendship, but it’s also a more plausible approximation of real life events, at least insofar as Israel’s memoir portrays them.

1. If Beale Street Could Talk

If Beale Street Could Talk is not a perfect recreation of James Baldwin’s book in terms of plotting, but Barry Jenkins made a film that is very explicitly evoking the feeling of reading the Baldwin novel, the tortured experience of Black love in a world with institutions that systematically tear apart Black families. Jenkins translates the anachronistic, elliptical, and emotionally driven style of Baldwin’s prose into extended character monologues and tight close-ups of characters staring lovingly into the camera, following the general beats of Baldwin’s story while also staying true to the esoteric mood of that story’s coming-to-grips with finding joy and connection in a bleak and hostile world. As pointed out in a piece by Mustafar Yasar II, the climaxes of the book and the film differ greatly, but they carry the same emotional weight, equally informed by the remarkably similar tellings of Fonny’s and Tish’s story that precedes them. It may not be a one-to-one translation of the original work, but it is the nominee that most faithfully adheres to both the narrative structure and the empathetic core of that source material.