A Case For Greatness: GHOST DOG: WAY OF THE SAMURAI

Classics never die, but they seldom get replaced. Cinema is populated with enduring, venerated works of art that deservedly adorn list after list, but those lists are rarely updated, and less often expanded to include new, equally worthy entries. Organizations that give out annual awards are constrained not only by the limitations of formatting, but perspective - they can’t anticipate which film will survive the buzz of its initial acclaim or success and become part of the cultural firmament. And then there are just certain films or even genres that too infrequently receive the critical attention they deserve, are too obscure to break through to bigger audiences, or just aren’t taken seriously enough to merit consideration alongside the ones we “all” already know we love or respect. A Case For Greatness, this series, tries to argue for, and to champion, forgotten or underappreciated films in a variety of genres that may be worthy of being called “classics.”

By the time Jim Jarmusch directed Ghost Dog: Way of the Samurai in 1999, he’d already become one of my favorite filmmakers. Down By Law combined whimsy and melancholy - and Roberto Benigni chanting “you scream-a, I scream-a, we all scream-a ice cream-a!” in a cramped New Orleans jail cell - in a way that perfectly appealed to my outsider tastes as a college student; Mystery Train shuffled around Memphis, exploring the mundane and mystical experiences of an eclectic group of characters, and introduced me to Rufus Thomas and Screamin’ Jay Hawkins. Night on Earth left me cackling as Giancarlo Esposito’s passenger, YoYo, hilariously discovers his driver, played by Armin Mueller-Stahl, is named Helmut. From his earliest days, he found the funny, sad and beautiful in everyday exchanges without trying to dramatize them, creating a singular kind of humanistic, unhurried poetry.

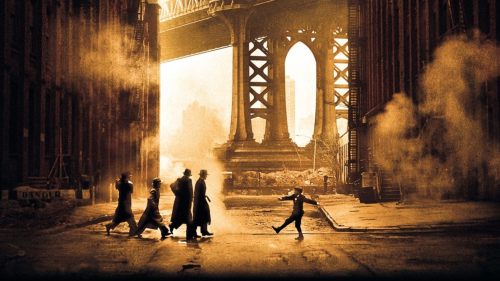

Ghost Dog initially felt like a strange departure from his previous work, but as soon as the opening credits ran, it flowed seamless everything else he’d done. Forest Whitaker stars as the title character, an assassin who serves as a retainer for a local mobster named Louie (John Tormey) in repayment for saving his life years earlier. After performing a job that leaves a witness at the site of the murder of a made man, Ghost Dog becomes a target for Louie’s boss Ray Vargo (Frank Silva), who sends his men throughout the city to find and eliminate him. Consequently, Ghost Dog hunts down Vargo and his men to kill them before they can return the favor. The assassin’s exploits are framed by quotes from Yamamoto Tsunetomo’s Hagakure, a spiritual guide for warriors that provides a meaning and motivation for his actions, and ultimately, Ghost Dog’s enlightenment, serenity, and acceptance of his fate - whatever that may be.

Whitaker is an undeniably imposing presence, but what’s remarkable about the film is how Jarmusch shapes his performance to be so intriguingly slight; in an early scene, he walks the streets, navigating his way around other pedestrians who behave as if they don’t even see him. Though he uses contemporary technology - not just handguns but an electronic “key” that allows him entry into cars, and later, the gates of Vargo’s mansion - Ghost Dog embraces anachronistic lifestyle choices that put him at arm’s length from the world around him, making him seem like a warrior from another time, trying to navigate his way through ours using the only code of behavior he knows. He is never flustered, never defensive, and always at peace; he maintains a coop full of pigeons, not just as his pets or companions, but his only method of communication, and prefers their company to most other humans’.

Jarmusch’s treatment of the mob, meanwhile, is less parodic than it is proletariat. Although Vargo is wealthy, his men all feel like working stiffs rather than glamorous goodfellas, overweight, poorly dressed and shuffling from one location to another at their boss’ beck and call. Not stupid but not especially smart, they are part of Vargo’s diminutive fiefdom, and he controls with a stoicism that’s more eccentric than it is intimidating - but they can’t tell the difference. Louie, caught between obligations he cannot refuse and a bond he doesn’t want to break, chooses the same as Ghost Dog would - to honor his master - but it’s only because of the samurai code that Louie has an opportunity to prevail over his “retainer.”

These philosophical catch-22s are exactly the kinds of ideas Jarmusch enjoys exploring, and here he does it in a context that feels both dreamlike and vividly real, culturally intersectional and wholly detached from any direct sense of inspiration. He was the first filmmaker to enlist Wu-Tang impresario RZA as a composer, and the rapper-producer’s work here functions more like a heartbeat for the character than a soundtrack; together, both artists cobble their work from samples that imitate and evoke in the service of creating something new. His use of not just Hagakure but Rashomon, two books prominently showcased in the film, evidences just a handful of the not just literary or spiritual but cinematic influences on its ideas. And finally, Jarmusch provides Ghost Dog with a best friend, a French ice cream salesman named Raymond (Isaach De Bankole), who shares no language with him but they always seem to understand each other anyway.

Additionally, Jarmusch peppers in cartoons old (Betty Boop) and new (The Simpsons) on TVs the characters always seem to be watching that either anticipate what is about to happen, or comment on the substance of what already has. It’s this odd, dry but evocative storytelling that elevates what otherwise might have been a conventional story of recrimination and revenge that audiences have seen dozens of times before and since. But this hip-hop samurai gangster story isn’t winking at its influences, nor at the audience; it’s staring deep into an abyss in search of meaning, with a premise straight out of pulp fiction, using a language that synthesizes the dialect of a distant past (the code of the samurai) and an undeniable present (the code of the streets). Once again, and as he would later as well in Only Lovers Left Alive and the transcendent Paterson, Jarmusch seamlessly combines the mundane and the poetic; where many movies make you want to live in their world, Ghost Dog: Way of the Samurai is that rare kind that makes you want to live by its rules.