The Ingredients Of JOJO RABBIT Stew: Richard Lester, Stanley Kubrick And RUGRATS

Jojo Rabbit is in theaters soon. Get your tickets here!

There are few filmmakers more gifted at juggling discordant tones - especially in the span of a few seconds - that Taika Waititi. He can pivot from harrowing drama to complete absurdity in a matter of lines of dialogue, and elicit a laugh almost immediately after wringing tears. But even for the director of What We Do In The Shadows and Hunt For The Wilderpeople, tackling World War II, and more specifically, Adolf Hitler, would prove a considerable challenge when time came to explore some ideas, and ideologies, that by any definition and in any era are considered poisonous, racist, and offensive. So the solution was, of course, to make Germany’s most infamous leader the imaginary best friend of an adorable 10-year-old boy.

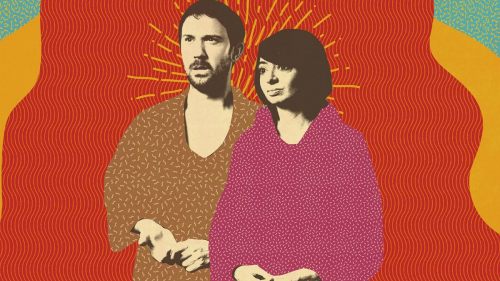

Just a day after Jojo Rabbit premiered at Fantastic Fest 2019, Waititi and one of his stars (and filmmaker in his own right) Stephen Merchant sat down with press in Austin for a spirited conversation about the minefield they waded into in order to bring this strange and unexpectedly delightful story to life. In addition to talking about a handful of the cinematic references they drew upon to find the right mix of tones, Waititi examined the conventions he chose to explore, and in some cases avoided, in depicting an era filled with prejudice, violence and bloodshed, and finally, he and Merchant reflected on the opportunities that comedy provides not only to test boundaries but to trick audiences into connecting with characters and stories that they might not have been ready to care about.

Taika, your films always dance on this really delicate edge of these discordant tones. What was the key to finding the right balance of irreverent, black humor and sentimentality?

Taika Waititi: With all of my films that I try to find that balance, and usually in the edit is where it takes a long time. I spent probably longer than other filmmakers in editing, trying to find that tonal balance. And I think that makes it harder in some ways to describe or explain them to people because none of them are pure. I mean, maybe with the exception of [What We Do In The Shadows], none of them are pure comedies, or pure dramas. They’re always a mix, and they go back and forth. In Wilderpeople, a very beloved character dies in the opening 15 minutes and then within one minute there's the most ridiculous funeral scene with an absolutely stupid speech. And doing that scene, I wasn't sure if it was okay - can you have the next 10 minutes of film dealing with the death and picking an audience out of there? Or is it more like real life where it's from a tragic moment straight into a comic moment and back again? Because that speech in that funeral was taken from my friend's father's funeral - so it was a real thing. And it was a tragic day, but I found the most hilarious moment in this funeral where guy was giving this ridiculous speech about confectionary. So this stuff does exist, and that's why I think life is more like that where from one moment to another, you're constantly on your toes. But for me the hardest thing is finding that balance. And listening to an audience as my main thing - asking them, what do you think of this moment? Were you ready for this?

Stephen Merchant: That reminds me of when I was at my grandmother's funeral and we were driving in the hearse and there was the driver and the reverend that was going to take the service and they were in the cab and we all sat behind them very po-faced and I could just hear the conversation between the driver and the vicar. And the driver said, “Do you drive, vicar?” And he said, “No, you have to choose between drinking and driving. I chose drinking,” and he started laughing. It's just another day at the office for them.

Collaborating as two filmmakers, what do you guys learn from each other and how do you inspire each other?

Merchant: I was a fan of Taika’s, I'd never met him, but for some reason I just could tell from having seen his stuff that we would hit it off. And I felt we did - I don’t want to be presumptuous. But I was very pleased that Taika’s directing style was very comparable to mine in the sense that he had strong ideas, but was very collaborative and allowed me to be playful with the script and with Sam Rockwell, and that's what I want from a director. I always just play the role of an actor - I would never try and impose my thoughts - but you like to feel like that you can be used and utilized, and it was sort of exactly what I hoped it would be.

Waititi: The times when I've worked with other people purely as an actor, I’ve sometimes worried that the director part of me was going to start taking over. But I feel like unless you’re a real egomaniac, you usually just come in and want to do the best work that you can to help someone to tell the best story they can.

The movie manages to highlight Jojo’s messed-up ideology without insulting him as a person. How tough - and how important was that?

Waititi: Well, I don’t think Jojo is an idiot. I mean, when the children were indoctrinated into the Hitler Youth and taught all of these ideas, they were very bright kids, very smart kids, but it doesn't mean that they were not easily influenced. And I think Jojo is exactly the same. For me, the Beatlemania parallel was that Hitler for Jojo was just like a pop star. I had posters of bands and whatnot when I was growing up in my bedroom, and I feel like in those days that Hitler was for young kids and for a lot of people in Germany, he was that pop star. So I think it's very easy to see how people can become enamored and brainwashed and fall in love with these personalities. And he certainly had a personality. Or so they say he was very charismatic and drew people in and had this air about him. I watched this documentary where they were saying that he would do this thing where he would stare straight through you and once he locked eyes it was like he'd sort of hypnotized you. Someone who actually met him was describing it, and the propaganda machine and the war machine and the way that they controlled the populace, they made him so beloved to the German people. I was always interested in that, because I feel like I'm a smart person. That wouldn't happen to me. But there were a lot of smart people in Germany who got brainwashed, and they believed in this strange, weird myth. And I think that also happens a lot, and you can see it today in America, that when people are poor and when they’ve got nothing - you have to remember that Germany came off the back of a great big depression and they had nothing. And suddenly someone comes in and “says what we're all thinking,” which is a classic thing that people like to say when someone comes in to pick poor people up. So I can see how that happens.

Merchant: I think also what's interesting is humanizing all of people with Nazi beliefs, because I think there's this tendency, this urge to demonize them as this other thing, that they're simply evil. And I think the danger with that is it suggests it couldn't happen again, or it couldn't happen to us. We're right minded people who are on the right side of history, and what we all know is that they're just other people that got seduced into that way of thinking because it played to whatever needs they had. And I think that's what Jojo inhabits very nicely, that he's a very sweet human kid who's, who's being seduced by the dark side. And I think that's still kind of important.

Do you tend to be a cinephile as a director? This definitely feels like Richard Lester meets Leni Riefenstahl meets Steven Spielberg. Were there films that you specifically drew upon that inspired you in terms of the technique, style or story?

Waititi: I'd like to think that I’ve been influenced by Dr. Strangelove. But then I did rewatch it, and it's not very emotional. But I feel like I've stolen from Badlands on every film I’ve made. I think you can see that in the forest stuff. And I think the relationship between the boy and girl was like Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek in some ways just these two weird kids. Heathers was another one that I visited for Elsa. I didn't want her to be an overly victimized, weak character, I wanted her to feel more like she was probably in the coolest group in high school and was probably one of the cool kids who picked on other kids maybe. Then again, you don't know. I feel if I was 17 having to live like that in someone's attic, I would be pissed. I would be so angry, knowing I'm good looking and I'm cool and having gone from this high school life to living like that, that was a more interesting version of that character for me. Because she could be manipulative and she could be angry and try and control this kid and work the situation to her benefit - because why wouldn't you if you've lost everything? You've got nothing left to lose, so why wouldn't you manipulate a 10-year-old boy and lie to him and do anything you could to survive.

Obviously you deal with sensitive subject material, talking about Jewish people and the caricatures and myths around them. Were you ever worried about taking that too far?

Waititi: Yeah, you’re always worried about stuff like that. The ad libbing and improvisation we did with Rebel’s character, for instance, who would go off on these anti-semitic tirades, I was encouraging it. Because I didn’t want anyone to like her. But there was a scene that we got rid of because it dragged the end out too far, but she's dying and an entire building has crushed her and it’s just her head, and she’s like, “tell Hitler I’ll see him in Heaven.” She’s never redeemed and I liked the idea of this super racist asshole being crushed by a building. But she would go off on certain things, and it was interesting that I think we even knew in the moment that it wouldn't be in the movie. It already felt like we were pushing it and we're not taking the story seriously or the point of telling the story seriously. So that never made it into the edit. And then we’d call cut and she’d be like, “I hated doing that.” And I’d go, “I hated hearing it, so let's just not do it again.” So sometimes when you’re improvising with people you feel like this is fun, but all you’re doing is making fun of people of other races, and it just leaves you feeling kind of sick - and so you put a stop to it.

Even though the movie deals with really dark subjects, you often don't show the people dying and some of the real atrocities that happen in the story. How did you decide how much to show?

Waititi: Well, I just feel like so many other movies did it better than me showing the brutality and the atrocities of war. I also wanted to keep it like Rugrats.

Merchant: Another big influence on your work.

Waititi: Yeah, Heathers and Rugrats. I wanted it to feel more from a kid's point of view and how they interpret some of these things. When I was a child seeing violence and things in my life, my memories of them are not accurate. I think they had been put through a child's filter where they feel more cinematic sometimes or they feel like pieces of art or cartoonish. And so I wanted to kind of keep some sort of innocence around this stuff and not be gratuitous. I didn't want to see anyone get shot. I didn’t want to put that in my film. And it's a little bit romantic with the operatic music and slow motion and all that stuff, but it’s still all from his point of view. So it was important to me not to be too graphic. I just don’t like feeling like it's just gratuitous or it’s just a filmmaker showing off. Because there's always that tendency, or you get lured into this idea of doing a big sweeping helicopter shot with things blowing up, and people will see every limb flying off. But it's just not really anything I was interested in doing.

Fighting With My Family and Jojo Rabbit explore a lot of themes that dovetail into each other - the idea of feeling like an outlier and how that actually bonds you to other people, for example. Why has that resonated with you, or is resonating with you right now as storytellers?

Waititi: Well personally, I just love stories about families. I'm always drawn to that, because I think that if you look at any of my films, they’re very family centric. And I know that I know my limits as a filmmaker; I'm not sure if I would have the patience or the focus to be able to do something like a very detailed and complex political thriller or something. I like the simple politics of families and figuring out those relationships with those dynamics, because I come from a really interesting family, with lots of different amazing characters. And that's always been my fascination, how all of these people can operate within this dynamic. And within families, you find every character type and every personality type, villains and heroes. So yeah, that's why I keep going back to it.

Merchant: Well, going back to the reason I knew I would hit it off with Taika is I like the idea that you can use humor as a way of seducing an audience, relaxing an audience, and then by the end hopefully you've made them choke up, get emotional, get teary eyed. That was certainly the ambition in my film and I think Taika’s as well. There’s something very seductive about using humor in that way and when I watched the final cut of Jojo, the thing I was not expecting was that halfway through I would start to get quite as emotional. In the room I watched, even with seasoned industry professionals, there was a gasp. Being able to reel an audience in with laughs and then turn the tables on them is an ambition of mine and I think Taika does it magnificently.