Collins’ Crypt: Universal’s “Not Classic But Still Good” Horror Of The ‘30s and ‘40s

When you mention the classic Universal horror era, the things that come to mind are Dracula, Frankenstein, Wolf Man... i.e. the big guns that have been released and re-released more times than anyone can count. The lavish collections for each monster (and wonderful boxed set containing the whole lot) make for attractive purchases and are loaded with excellent bonus features, but there's a slight issue with this approach: they're cherry-picking the most iconic entries (and their hit or miss sequels) while leaving the rest of the studio's output of the time unheralded. Over time, it has started to feel like Universal had a perfect record for creating legendary monsters that have endured in the public consciousness for nearly a hundred years without making any other horror films.

But as you hopefully know already, that isn't true. And over the past year, Scream Factory has been filling in the gaps of that era with their Universal Horror Collection sets, the 4th of which is hitting stores this week. I wrote about the first volume when it was released last June, and a new one has come out about every three months since - each with four lesser-known but still interesting films from the era, complete with historian commentaries that provide context for the hows and whys they came together. Not everything could feature a character that was bound to create a lifetime of nightmares (and merchandise); they had to pad their output with B-movies and programmers, on lower budgets than the "classic monster" films were given to boot.

That said, they'd usually rope in audiences by casting one or more of the horror icons, albeit in less showy roles than the ones they were known for. The first volume collected four of the times that Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff appeared in the same film, but subsequent sets haven't had any kind of noticeable theme other than, obviously, being from Universal. But Karloff and Lugosi have popped up in a few of the films, as well as fellow frequent faces like Lionel Atwill, Lon Chaney Jr, and even a very young Vincent Price (in volume 3's Tower of London), and some of the films even reuse footage and/or music from the classics (one film here uses the foggy forest from Wolf Man's opening credits and a burning building from Ghost of Frankenstein), so they're never going completely off-brand - if you think of Universal's historic output from the '30s and '40s as a tree with the classic monster films as the trunk, then these films are the branches that round it out.

Volume 4 breaks "tradition" for me in that it's the first time I've actually seen one of the movies before. Night Monster, a 1942 film that was a loose remake of Doctor X (you know, the one who "will build a creature"), played in the obligatory "old black and white movie" slot at one of the New Beverly all-night horror marathons, and per my writeup I didn't fall asleep! That said, it's been so long I barely remembered anything about it other than the fact that Lugosi didn't quite deserve his top-billed status, as he was merely a supporting character - the butler of the obligatory Old Dark House where it took place. If you've never seen a film of this type, they're all pretty similar: a bunch of folks in an isolated manor are besieged by unexplained events and even murders, and more often than not the explanation is grounded in reality, with the motive usually involving an inheritance or buried treasure.

Not the case here! In many ways, it's essentially the first slasher movie, as the body count is much higher than any "old dark house" movie I've seen, but it's also completely revenge-driven as opposed to the usual money-themed motivations. Granted, there isn't a lot of on-screen violence, but I was legit kind of stunned to see how many corpses piled up by the time the movie ended, in addition to my surprise that the killer used supernatural means to carry out his murders, as these things tended to rely on hidden passageways and parlor tricks to explain their "horror" elements. It's also got some terrific (for its time) sound design, letting some of the scare scenes play out in near-total silence with only something like a croaking frog to assure you that the audio is enabled. It's a shame Lugosi has so little to do (I'm not even sure if he survives? He just kind of disappears), but as long as you put more stock in the scenario and general vibe than his appearance, it makes for a good time.

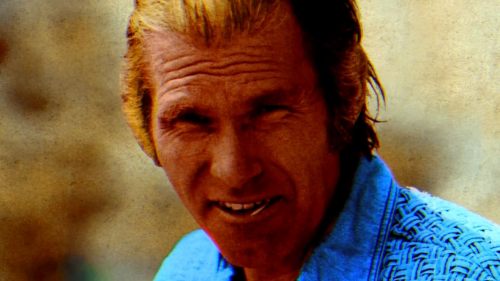

However, the real gem of the set is House of Horrors, which featured Rondo Hatton in what was meant to be his breakthrough performance as a horror star, after making his mark in a Sherlock Holmes film where he played a murderer known as The Creeper. The character (or at least, the name "Creeper" - the continuity would be a NIGHTMARE if all three of them were supposed to be the same guy) returned in House of Horrors and The Brute Man, both of which were shot the year after the Holmes film was released and would presumably elevate him to the same status that Lugosi and Karloff had enjoyed in the '30s. Unfortunately, the actor passed away (from a heart attack relating to the acromegaly that gave him his distinguished features) before either of those films were released, making these the only horror films he appeared in. The annual Rondo Hatton Awards, which celebrate the horror genre in film, television, and writing, are not only named after him but the award itself is designed in his image as a tribute to the actor who never got to enjoy his genre success.

The plot of House of Horrors is somewhat similar to The Raven from Volume 1, in which Karloff played a murderer who performed a few hits for Lugosi's crazed doctor, seeking revenge over feeling slighted. Here, it's an artist (Martin Kosleck) who is mocked by an influential art critic and is so upset about it that he's planning to kill himself, but instead sees a nearly dead man in the water and decides to play hero instead, rescuing him and bringing him home. Quickly realizing that the man is the notorious Creeper from the papers, Kosleck decides to use him to carry out his revenge on the critics. So he'll casually say like, "Ugh, this one critic is a real jerk!" and Hatton, not really caring who he kills, nods and takes off into the night to do the deed. The scheme works for a bit since another artist is suspected of the murders, but eventually the cops close in on the pair before they wipe out the entire critic base of New York. Hatton's imposing performance and some fun supporting characters (in particular a coroner who seems excited about the extra work) make it a pretty easy way to spend 65 minutes.

The other two films aren't as good, but they both have Karloff so they got that going for them. The Climax began life as a Phantom of the Opera (1943) sequel until it was rejiggered, but they used some of the same sets to cut down on costs. Karloff plays the theater's in-house doctor who becomes obsessed with their newest star, mainly because she reminds him of a previous starlet that he killed in a jealous rage. Will history repeat itself? Maybe, probably, but you have to sit through several interminable musical numbers and even some broad comedy to find out, with spreads the already minimal horror element of the Phantom story even thinner. And Night Key isn't even remotely a genre film; each of these sets seems to include a straight-up crime thriller and this fills the slot this time around, with Karloff as an inventor who is forced to help some bank robbers do their thing. It's fun seeing the icon as a meek, kind of pathetic character (with bushy hair and glasses, presumably an attempt to give him an Einstein-y flair), but my general disinterest in this kind of thing makes it hard to gauge whether or not it's a strong example of the sub-genre.

But even still, it's always interesting to see these movies, which are all accompanied by historian commentaries that, when well researched, can provide a nice snapshot of the studio at the time as well as what was going on with the performers (in Night Key's case, Karloff was contracted for a movie but they didn't want it to be horror, as such films were currently in decline). Are any of them likely to get watched as often as Bride of Frankenstein? Of course not, but it's important to see the whole spectrum of an era's output as we get further away from it. It's easy to say that the '90s had a lot of forgettable stuff when you lived through it, but fifty years from now, when Scream, Seven, and Candyman are among the few films still being namechecked and watched, our grandchildren will get the idea that the decade was infallible. Relatively speaking, these collections offer the Brainscans and Event Horizons of their day; the imperfect films that didn't become genre landmarks but were plenty entertaining to the audiences that saw them then. Here's hoping Scream Factory keeps making sure they are preserved alongside their more famous peers.