Winning The Media War In THREE KINGS

“Are we shooting?”

The opening line of David O Russell’s Three Kings is a meta wonder; Mark Wahlberg runs into the frame as the camera glides across a flat, baked desert, and then he stops and looks to the side and yells, “Are we shooting?” with a look of genuine confusion on his face. From offscreen someone answers with a muffled “What?”

It could be an outtake, and starting the film on this note is thrilling, cinematically and thematically. For a brief second you’re just as unsure of what you’re seeing as Whalberg’s Troy Barlow is. Then the follow-up: “Are we shooting people or what?”

The camera whips around to pick out figures in the distance, soldiers putzing around, dopey Conrad Vig (Spike Jonze) trying to get sand out of someone’s eye. The camera, which had been smoothly moving forward, is now herky jerky as it zooms in, blasting us out of elegance into journalistic verite. Russell does this again and again in the movie, bouncing from perfectly composed shots to handheld, from highly stylized looks at internal organs being damaged to unsettlingly realistic torture.

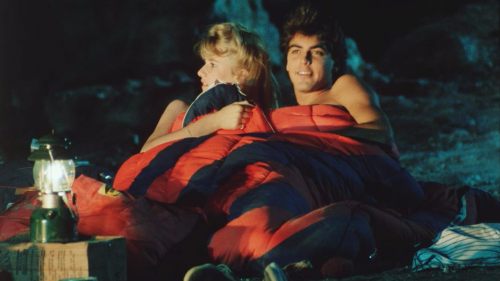

That play with reality continues after the credits, as we watch Nora Dunn’s reporter flubbing her lines, making the stuff we’re watching actually outtakes. That’s all against the backdrop of soldiers partying, drinking, having fun - footage that could be of real soldiers really letting loose. Russell goes from verite - a soldier has a water fight with the camera as it glides through the party - to gloriously stylized - a shirtless hunk bounces in slow motion, immaculately lit and glistening.

This is a media war, we’re told right after we see the army fucking the media (or the media fucking the army, depending on how you look at it) when Archie Gates (George Clooney) is introduced. This is the crux of Three Kings - the back and forth between perception and reality, which plays out in the story but also in the filmmaking. For Americans back home the Gulf War was a weird, bloodless conflict - when Dunn says the war exorcised the ghost of Vietnam she’s only saying what we all hoped was true - but in country it was something else. For the soldiers whose boots were on the ground combat in 1991 may have been less than eventful, but for the Iraqi people it was profoundly horrible.

“What is the problem with Michael Jackson?” Captain Said (Said Taghmgaoui) asks Troy, opening the interrogation scene. It’s funny but it’s pointed - this is part of the media war. The media has made Michael Jackson, the international King of Pop, hate himself so much that he has taken the most drastic measures possible to change into something more acceptable, something whiter. Said tortures Troy into an understanding of cultural semiotics, breaking through the bullshit excuses for the Gulf War - liberating Kuwait! Helping children! - and making him drink black oil, the true reason American soldiers are there. It’s no different from Troy, Conrad and Archie’s quest for hidden gold, except the American command knows exactly where their treasure is and how to get it out.

Russell cuts away during this interrogation to Said’s son being killed in his crib and to Troy’s child and wife, first walking happy down a street and then - when Said has cracked Troy - being blown to pieces. It’s powerful, and Russell plays these cutaways silently, with just the dialogue of the interrogation over the shots. He’s taken a torture scene and somehow made us feel bad for the torturer. It’s one of the movie’s many masterpiece-level reversals of tone and understanding.

This is the turning point of the movie, where the characters come to understand the reality of American interventionism - it’s not for the people there, it’s for the people back home - and rebel against it in their own way. It’s possible to turn Three Kings into an apology for the Iraq War (George W Bush had to finish the job his dad left undone!) but here at the end of that war the same sick joke is playing out - the Americans have come back to Iraq, broken it, gotten what they needed and left. This time it just took longer to get out of town.

At the end of Three Kings the surviving characters trade all of their gold to get refugees into Iran, away from the vindictive forces of Saddam. George Clooney, still a TV star but using his familiarity in American homes to incredible effect, does what the US should have done - help the people, not hoard the wealth. Reality is, of course, seldom so selfless or clean.

But David O. Russell knows that. He has Archie Gates explain it, metaphorically, early in the movie. He’s telling Vig why getting shot is bad, and Russell shows us a bullet ripping through internal organs. Green bile oozes from the wound. Gates says:

“Specifically, the worst thing about a gunshot wound, provided you survive the bullet, is something called sepsis.”

“Infection of the blood,” Chief Elgin (Ice Cube) adds.

“That's right,” Gates continues. “Say a bullet tears into your gut. It creates a cavity in the dead tissue. That cavity fills up with bile, and bacteria, and you're fucked.”

That’s why Gates wants to do the heist without shooting - to avoid not gunshot wounds but the aftermath of gunshot wounds. But he’s too late. The army was the bullet, and they’re standing deep inside Iraq’s wound, one that has been filling with bacteria. By the end of the movie Gates understands that. He sees the truth beyond the media war.

When Warner Bros was thinking of rereleasing Three Kings in 2004 to cash in on the newest war in the Middle East they commissioned Russell to make a documentary about that war for the DVD. The rerelease got scrapped but the doc, called Soldier’s Pay, ended up airing on IFC the night before the presidential election. In an interview with CNN, Russell said:

Every Iraqi I know is glad that Saddam Hussein is gone. I would completely disagree with Michael Moore about that. I think it's good that Saddam Hussein is gone. And I think basically the movie takes the position of, is Iraq better off without Saddam? Yes. Is the world better off with this war? Not sure, don't think so.