THE LIMEY: Movie As Memory, Memory As Movie

The Limey is a movie that’s always looking backward. That’s true in a very literal sense: the movie starts at its finale - at its "present." And much like life, the present is kind of dark and confusing, and we’re not sure what’s happening. Then the film backs up, in fits and starts, stitching together disconnected moments in time, and we gradually come to find out how the two men in the opening seconds got themselves there. Wilson (Terence Stamp) is a recently released ex-con whose daughter has died under suspicious circumstances. Wilson has come/will come/is going to Los Angeles to find out how and why. He moves through a Los Angeles that is absurdly funny, casually violent and largely populated with people over 50 whose best years are behind them. These people aren't blatantly evil so much as amoral, desperate to hang onto their things, their memories, their comforts. Through this world, Wilson is moving forward, and God help anyone who gets in his way.

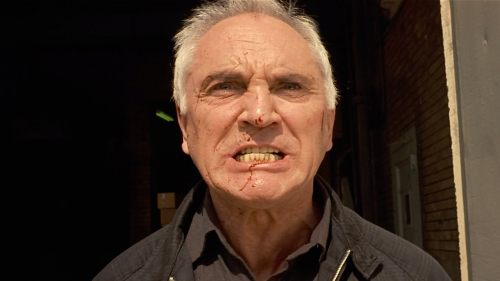

Director Steven Soderbergh cannily casts his pulpy-on-paper revenge story with '60s relics, infusing the whole film with a constant awareness of - though not necessarily a fondness for - the past. Looking backward is indeed a high for some of the characters. Through Terry Valentine (Peter Fonda), the film’s unlikely villain, Soderbergh expertly conveys the allure of living in the yesterday. Valentine is a record producer from the Sixties, introduced in the film via a giddy, seductive “greatest hits” montage; it has a good beat and you can dance to it. Obsessed with keeping his girlfriends young, his teeth white and his hair perfect, Terry’s life is built on the precarious cliff of nostalgia, and he knows it. At one point in the film, he dreamily describes the '60s to his barely-legal plaything: "Did you ever dream about a place you never really recall being to before? A place that maybe only exists in your imagination? Some place far away, half-remembered when you wake up. When you were there, though, you knew the language. You knew your way around. That was the Sixties...No. It wasn't that either. It was just '66 and early '67. That's all there was."

While Valentine stares at himself in the mirror and waxes romantic about the past, our protagonist Wilson has a different take on looking back: he’s not a fan. It hurts. The past holds nothing but pain and sadness for him. Perhaps this pain, as much as the mystery of his daughter’s death, is what sends him forward, forward, ever forward. In a neat trick, Soderbergh pits the two adversaries against each other, while simultaneously having them run in opposite directions from the here and now.

Soderbergh says the film’s style - visually hopping backward and forward in time like an actual stream of consciousness - was an experiment in finding new ways to deliver information to the viewer and not, as many assumed, a riff on the New Wave-flavored editing of John Boorman’s Point Blank. Soderbergh’s ultimate goal, to hear him tell it, was to reject the notion that films are unable to show a character's thinking on screen. Diving into this non-linear delivery method after toying with the technique in Out Of Sight, the effect in The Limey plays less like a thought process, and more like the emotional associations of memory. Even expository or character-building moments have the unreliable quality of memory to them: did a particular conversation happen over dinner one night? Or during the walk after dinner? Or was it in the living room? It’s as if the characters remember it happening in all those places, so that’s what we see.

Not content to rely solely on editing to delve into time and memory, The Limey takes a somewhat unprecedented jump into another movie altogether, re-purposing footage from 1967’s Poor Cow to show Wilson in his youth. The footage, showing a 29-year-old Stamp as a petty criminal in the UK, has been somewhat re-contextualized; it’s not explicitly, as some have said, a quasi-sequel to the Ken Loach film. But the effect is striking, putting the veteran actor's "baggage" explicitly onscreen, and suggesting not incorrectly that our memories are but movies playing in our head. (And as I typed that line, it first came out “our movies are memories playing in our head.” Make of that what you will.)

The Limey’s unique presentation also turns Soderbergh’s grief-stricken anti-hero into a time traveler. Wilson’s present, with the one real love in his life gone, is so very terrible that he seems unable to remain there too long, his impatient mind jumping forward toward the imagined closure that might come with killing his daughter's murderer. But over and over his grief pulls him relentlessly into the past, where every frame is tinged with longing and regret. Much as our minds warp time - elongating it, compressing it, looping it on itself - Wilson’s existence is a mournful mixtape of moments from his past, present and future, put on shuffle and repeat.