Tribeca Film Festival Review: MAGGIE

A lot of us have reached the point of zombie saturation. It’s an overblown sub-genre that’s lost a lot of its meaning, and would’ve probably gone into hibernation a few years ago were it not for The Walking Dead. We also seem to be sick to death of things that are dark or dour when they have the option not to be, and Maggie, being a combination of the two, should by all accounts not work. Yet somehow it does, and while it falls short in a lot of respects, the un-dead and the un-colourful end up working in its favour. I’m sure you’ve all heard the spiel about how zombies work best as social or political analogues (Communism! Consumerism!), and while that’s most certainly true, Maggie takes it a couple of steps further, colouring within the lines of the genre but changing the specifics at every turn to make it matter on a micro level, even though it kind of flubs it at the very end.

The film assumes you don’t live under a rock and opens with Abigail Breslin’s Maggie Vogel having already been bitten while wandering a deserted city in the Midwest. Her father Wade (Arnold Schwarzenegger) is already out looking for her when she’s picked up by doctors who specialize in this sort of thing, so we’re already well into the zombie situation when things get going, but the danger the film deals with is more personal than apocalyptic. The main conceit is that rather than an immediate or even a day-long transformation, turning into a zombie is something that takes weeks, maybe even months, with the usual aggression and hunger for flesh setting in gradually alongside the rot. It’s not so much dying and coming back to life as a monster as it is a painfully drawn out descent, akin to waiting for Alzheimer’s to set in all the way, or waiting for a terminal illness to run its course. Rather than being about survival, it’s about dealing with the inevitable.

It’s also equally a stand-in for puberty, the scary physical changes that a teenager goes through that are both external, like waking up to discover something new about yourself in the mirror, but also internal, causing Maggie to be withdrawn from her father and her stepmother because of how much she grows to resent herself. The world around her is bleak, and it’s growing increasingly hard for her to get past her cynical outlook (with good reason!), but there’s also a glimmer of hope despite the fact that there’s no known cure, because the knowledge of her impending death allows her to re-connect with her old friends, and even better understand her ex-boyfriend, with whom she parted ways when he was first bitten several months prior. It’s also an opportunity for Maggie and Wade to get some of the father-daughter time they seem to have missed out on.

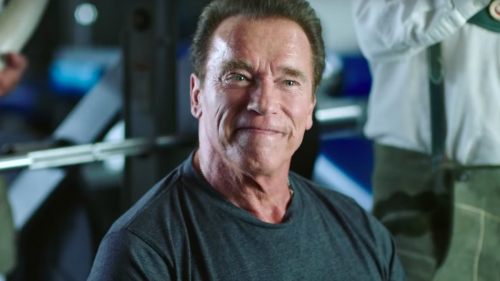

The film’s major selling point is that it’s a zombie movie starring Arnold Schwarzenegger, but it’s also the complete opposite of what it sounds like. There’s neither action nor the opportunity for one-line quips, and the one time Arnold is allowed to use a shotgun, it’s to put down a neighbor and his young daughter, whose condition has been allowed to worsen. It’s a quiet performance that takes place entirely behind the eyes, as Wade is a man who clearly doesn’t wear his heart on his sleeve, but has to make an extra effort to reach out and reconnect with his dying daughter. There’s a certain charm to Wade that comes through when he opens up about the things that mean the most to him; his late wife, his old car, and finally, his daughter. He’s a man who, despite the inevitable, does whatever he can to keep his new family together. Well, he sends his younger kids away to keep them from getting infected, but it’s the thought that counts! What he wants more than anything is to hold on to his baby girl a little while longer before she’s snatched away from him, either by the disease, or by authorities that want to quarantine her.

The film has an exceedingly muted colour grading, so much so that it may as well be sepia, but it’s coupled with what is clearly a colourful production design, indicating the world that once was, and even a household that once was. Wade even spends most of the film in a colouful checked shirt, one that feels weighed down by all the death he’s had to endure. His farm was once a place of colour and joy that’s now marred by social and personal disconnect and a sense of hopelessness, which makes it all the more noticeable the few times colour is allowed to bleed through in the form of flames.

The purging force of fire takes on a distinct reflective quality in Maggie, its destructive nature giving way to the kind of reflection that mirrors can no longer provide when all they see is rotten flesh. In a world devoid of life and passion, fire becomes about introspection. A reminder of the things it used to represent to people. A reminder of the life they once had, and what they have to do to hold on to what’s left. The film is a slow burn, sometimes too slow, but its pace being sacrificed is less a function of lacking in material and more because it wants to take the time to put its characters through the wringer by making them think about what really matters. Their physical suffering is a given, but moments like Wade watching his crops burn, or Maggie sitting around a campfire with her friends for what might be the last time, are the kind of things this zombie movie is really concerned with.

Sadly, all its internalization renders a couple of its major final scenes almost meaningless, though it might be the fault of those scenes themselves, and it’s a painful shame because the other 90% of the film is so damn good. After Wade has had to weigh the various methods of putting his daughter down versus sending her to die in a camp with the other zombies, Maggie decides she wants to go out on her own terms, but instead of allowing this decision to play out in a way that feels connected to what’s come before, the film goes in an almost disappointingly conventional direction, opting for a scene where the central focus is tension as opposed to anything character-centric (one of the characters is actually asleep) and it feels lifted straight from a bad horror movie. It’s predicated on the assumption that impending gore or violence (perpetrated by Maggie against her father) is something that matters in a film that’s spent most of its runtime ruminating on its inevitability. All the decisions that could possibly arise from a scene like this are foregone conclusions, because they’re a product of character developments that have not only already taken place, but have reached their inevitable end-points. It’s a dull scene where the outcome is exactly as expected, especially since Maggie’s entire story has been about her slowly losing control over her life, and her final victory where she momentarily snatches it back is hard to treat as anything but a consolation prize because it’s immediately followed by yet another cynical literalization of the entire zombie concept in the form of what action she decides to take. Ordinarily, something as minor as a single scene wouldn’t be enough to bring a movie down this much, but it has a sort of shattering ripple effect, almost unintentionally re-contextualizing the entire film to suit this bizarrely conventional narrative climax.

Ultimately, Maggie is a thoughtful film that uses a familiar genre to explore fatalistic ideas through a personal and immediately relatable lens. Even though it’s eventually undone by its stubborn adherence to a genre it spends so long subverting, it’s a film that tries to be different and mostly succeeds, all while looking absolutely stunning in the process.