“Ditto”: The Pop Motion Picture Catharsis of GHOST

It’s not hard to understand why Ghost became such a massive box office success ($505 million worldwide on a budget of $22 mil). The film addresses a fear/fascination all are faced with – namely, the act of dying and moving into the beyond. Yet outside of these primordial, intrinsic miseries, it’s a spectral story about the things we never want to leave undone once we shuffle off of this mortal coil. Were you able to pick and choose your hauntings, who or what would they be?

Ghost takes the idea of the horror movie and morphs it into something peculiarly saccharine; a chronicling of one prematurely deceased’s inability to say goodbye to the woman he loves. However, even on an aesthetic level, it asks the audience to consider choices they make in their everyday lives. For example: if you had to pick one outfit from your closet to spend the rest of eternity in, you surely wouldn’t throw on just any old long-sleeve polo.

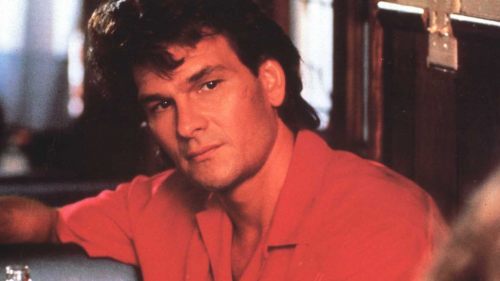

The plot of Ghost is incredibly simple. Sam Wheat* (Patrick Swayze) is a Master of the Universe-type banker who recently moved into a new, gargantuan Manhattan apartment with his sculptor girlfriend, Molly (Demi Moore). One night – after seeing a production of a similar fictional “charmed life” in Macbeth – Willie Lopez (Rick Aviles) mugs the couple, shooting and killing Sam after demanding his wallet. Sam now finds himself to be the titular phantom, wandering around New York as he learns the ropes of the spirit world. All the while, he’s forced to watch Molly grieve his passing as he investigates his own murder, discovering that the robbery wasn’t random at all. It was a staged attack set up by Carl (Tony Goldwyn), a man he thought to be his best friend, but who actually had Sam murdered after the banker stumbled onto suspicious accounts, into which Carl was embezzling money.

Though the basic themes of Ghost are indisputably timeless, Jerry Zucker’s first directorial effort away from his ZAZ partners belongs to the decade it helped kick off. Where Spike Lee was perfectly capturing the volatile, racially diverse Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn just a year before with his masterpiece, Do the Right Thing, Zucker’s picture is incredibly Caucasian, existing in high-ceilinged strongholds. It’s in these bastions of manufactured taste that Sam and Molly attempt to wall themselves off from the city’s danger. Ornamenting these seemingly impenetrable palaces are the fashions and décor that would come to dominate Hollywood output during the 1990s. Moore is draped in overalls and fashioned with a Caesar haircut that is still anomalous twenty-five years on. The impossibly massive loft Sam and Molly were set on spending their lives in is a marvel of gaudy pillars and perfectly arranged furniture, each piece looking hand-picked from the trendiest outlets. Perhaps the biggest casualty to this “yuppie chic” motif is Tony Goldwyn, whose scheming bad guy is basically one Brooks Brothers suit away from existing as a cousin to Patrick Bateman, right down to the murderous impulses.

Yet for all of the trappings of its time period, these choices seem deliberate, not only from a pop standpoint (as Zucker is very much working in a commercial mode), but also in how they help to establish the fantasy world of Ghost. Sam and Molly were very much the unattainable ideal for many people alive and going to the movies in 1990. They’re an NYC dwelling duo comprised of a moralistic man (with seemingly unlimited access to money), who is able to help build a home for his sculptor partner, complete with a studio in which they can have sloppy clay sex (OK – so maybe the clay sex wasn’t in anybody’s dreams). The existence of Sam of Molly is one that only subsists inside of motion pictures, and helps to heighten the starry-eyed make-believe Ghost indulges. This is the stuff of near-Sirkian melodrama, sans German sarcasm; emotionally universal but completely connected to the culture of the time – Pop Filmmaking 101.

Patrick Swayze is saddled with quite a difficult task in Ghost, in that he mostly has to be a passive observer to the action happening around him. It’s a reactionary performance, with Swayze selling the audience on Sam existing within another reality running parallel to the one the rest of the performers in the frame currently populate. For the most part, the movie star pulls it off, becoming an emotional lost boy with whom the viewer shares a psychic connection. We often find ourselves inside of Sam’s shoes, wanting desperately for the other characters to just acknowledge our existence and tell us that they can feel our presence in the room. One of the central thesis statements in Ghost is that, once you are dead, you have to learn to adapt to the idea of not being any further. Life goes on. Anything beyond your memory doesn’t matter. Being a romantic interest after Dirty Dancing was old hat to the action stalwart, but Ghost proved that he could tap into his own pain (namely the death of his father, Jesse Wayne Swayze) in order to produce a character that was equal parts relatable and phantasmagoric.

Demi Moore, on the other hand, is fighting a different sort of artistic battle, as Molly is somewhat underwritten. Bruce Joel Rubin’s Oscar-winning script reduces the artist to a grieving caricature, torn between losing a man she loved with all of her heart and another who is currently plotting to slide into the deceased’s place. Much of Moore’s screen time is devoted to crying and incredulously questioning the happenings Sam triggers to try and get her to believe he’s still with her. Thankfully, cinematographer Adam Greenberg (The Terminator, Near Dark) immaculately frames and lights Moore so that she never appears less than angelic. So while you can feel the actress struggling to add depth to Molly’s paper thin sketching, Greenberg ends up giving her quite the visual assist. Master editor Walter Murch then strings together these striking takes into a cycle of liberation, Molly’s anguish becoming yet another weapon for Zucker’s film to wield.

If it weren’t for Whoopi Goldberg’s psychic huckster, Oda Mae Brown, Ghost would undoubtedly tip over into being yet another piece of exclusionary Hollywood entertainment (and it’s depiction/narrative utilization of “thug” Willie Lopez still calls the movie’s weird racial politics into question). Thankfully, Goldberg completely owns every scene she’s in, starting off as stock comedic relief before quickly transforming her character into a literal vessel for emotional catharsis. Whoopi is on fire in every scene, but never seems to overplay Oda Mae at all, striking the perfect balance between clowning histrionics and genuine poignant beats. In short, Oda Mae becomes the core that holds the movie together right when it tiptoes on the edge of collapsing under its own cloying weight. For all of the movie’s weird, white-bred fantasy, Goldberg emerges as the shining star in this vanilla galaxy.

Any writing about Ghost would be incomplete if it didn’t mention Vincent Schiavelli. The consummate character actor’s mentoring subway spirit comes in as a close second to Goldberg’s medium in terms of scene-stealing. Schiavelli utilizes his bug-eyed, saggy features to his advantage, creating a lunatic haunt that feels more Ghostbusters than anything else (really all he’s missing is an ectoplasmic sheen). He’s an actor who knows how to make a strong impression in a short amount of screen time, entering the film running and screaming at Swayze. But he also ends up being both the new ghost and the audience’s guide to this uncharted netherworld; carefully passing down the rules regarding not only how these spirits live, but also how this cinematic universe operates. Exposition is a difficult dish to make taste delicious, but Schiavelli succeeds. His subway ghost is a great supporting character that stands out on the fringe – a kitschy ornament on an otherwise ordinary cinematic Christmas tree.

This is how Ghost became a sensation – it’s a moment of weird cinematic alchemy that really shouldn’t work at all, especially not on the ubiquitous level of awareness it achieved. A love story about letting go of the ones you love and accepting death as a natural part of existence? Sounds like something more attuned to art house audiences instead of AMC Cinemas. But that’s the genius of Jerry Zucker. Just as the earliest ZAZ comedies approached the direst of topics with a gigantic grin on their faces (John Landis’ The Kentucky Fried Movie remains positively subversive to this day), Zucker tackles giant, universal leitmotifs of mortality and packages them inside of a pop song. As the soundtrack is noodling “Unchained Melody” into your ear, the rest of the movie is forcing you to stare into an abyss you ultimately will have to dive into headfirst someday. Just make sure that you dress for the occasion, as it’ll be the last time you get to change clothes forever.

*Actual character name