ROAD HOUSE At 30: “Pain Don’t Hurt” Says It All

Road House is celebrating its 30th birthday. It’s one of the most ridiculous films ever made. In Road House’s world, skilled bouncers are not just well-regarded by their peers – they’re living legends, mythologized and revered in shouts and whispers. And they aren’t just skilled fighters – the best of the best is capable of executing what can only be described as a Mortal Kombat fatality. A corrupt businessman doesn’t just strongarm people – he commands a goddamn monster truck to level their businesses (and aside from its use in impromptu building demolition, Road House’s monster truck is apparently perfect for discreetly spying on people) The businessman’s gang of goons don’t just work for him for the paycheck – they revel in their evil. His second-in-command actually stops to laugh maniacally after blowing up a kindly farmer’s house. To deny that Road House is deeply goofy would be ridiculous. And to deny that Road House is really, really well-crafted and features some genuinely great action would be like saying Mad Max: Fury Road is slow-moving and lacks momentum.

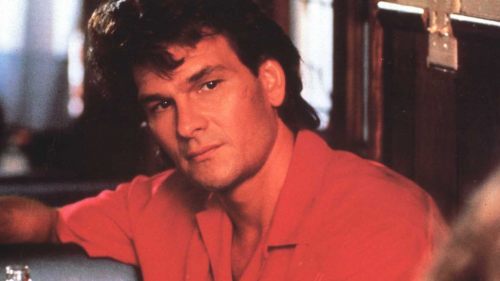

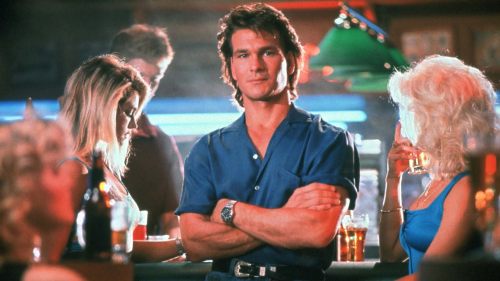

Despite its frequently baffling world Road House is not a smirky movie. It is not pointing and laughing at the fact that Patrick Swayze’s Dalton is a wandering super bouncer who practices both Tai Chi and kickboxing and holds a degree in philosophy from NYU and can claim with complete sincerity that “Pain don’t hurt.” It is not amused by Ben Gazzara’s fiendish real estate baron Brad Wesley angrily sitting in a rocking chair while he spies on Dalton and his love interest Doc (Kelly Lynch). It doesn’t stop to point out how “wacky” its ensemble’s propensity for pulling large knives from who-knows-where is. Even the monster truck is taken as a given. The result of this is that Road House’s zonked moments never feel artificial. This sincerity gives Road House’s leading men the space to build their characters into genuine, and in Swayze’s case, even dimensional characters. Although they only share a single scene together, Swayze, Gazzara and Sam Elliott (playing Dalton’s mentor Wade) play off of each other quite well, ably assisted by director Rowdy Herrington and editors John F. Link and Frank J. Urioste’s skillful story construction.

Swayze plays Dalton as cool, thoughtful and haunted by his mysterious past. When he first arrives at Frank Tilghman (Kevin Tighe)’s crumbling club the Double Deuce, Dalton lays down his law to the staff. He emphasizes the importance of politeness and emotional detachment, much to their initial befuddlement. He reacts to angry guests vandalizing his car with wry amusement. When Dalton practices Tai Chi, Swayze moves with grace and care. As Dalton’s feud with Brad Wesley escalates, Swayze stiffens up – the guard Dalton constantly puts up changes from professional to personal. Wesley reminds him of his past, a past that Wade warns him he’s still caught up in. Dalton’s workout shifts from Tai Chi to kickboxing, and Swayze plays it as an attempt to cope as much as it is an attempt to stay fit – Dalton is angry, and he wants to burn himself out before he explodes.

Neither Elliott nor Gazzara have storylines as complex as Swayze’s. Wade is in town to back up his apprentice and friend. Wesley is a power-mad, vindictive creep. But both Elliott and Gazzara breathe life into their characters. Elliott’s Wade is amiable and laid back, even in fights. He gets serious when he realizes how far the stakes have raised, but his main priority is always his and Dalton’s survival. Gazzara renders Wesley entitlement and wrath given form. He is at his happiest when ostentatiously showing off his power and wealth, even if his only audience is himself. Every action he takes in Road House is dedicated to reinforcing THE MIGHT OF BRAD WESLEY, from abusing his wife Denise (Julie Michaels) to sending the monster truck through Stroudenmire (Jon Paul Jones)’ car dealership to trying to murder Dalton with spears. Gazzara bounces Wesley between simmering rage and sadistic glee before ending on exasperated exhaustion – the world is not obeying him as it should, and it makes him very tired.

The contrasts Herrington and company build between Road House’s leads are a prime example of how well made Road House is on a technical level. It tells its story, silliness and all, really, really well. Nowhere is this more evident than the climactic battle between Dalton and Wesley’s right-hand-man Jimmy (Marshall Teague). Their fight is linked in parts in the opening paragraph, and a full version is below:

The great Dean Cundey’s cinematography renders the battle elegantly, tracking and emphasizing Swayze and Teague’s movements. The fighting and stunt work, coordinated by Charlie Picerni, gives each man a distinct style. Dalton goes for quick, decisive moves to end the fight as quickly as possible. Jimmy wields a flashier style that indulges his sadism and emphasizes causing as much pain as possible. Both men break down as the fight continues and their blows take a toll. When Dalton kills Jimmy by ripping out his throat, it’s both a decidedly decisive end to the fight and a strong character beat – the war with Wesley has made Dalton both angry and desperate. For someone who makes a point to avoid violence when possible to kill, and kill in such a brutal fashion, is a sure sign that things are getting very bad. At 30, Road House remains a flummoxing and glorious treasure of a movie.