Yes, ROAD HOUSE Is A Modern-Day Western

Road House is very distinctly American. It’s a working class film set in the heartland, featuring a community of kind hearted folk getting screwed by a rich asshole. Jasper, Missouri is just rural enough that the local law enforcement has little recourse against a guy with a lot of money and hired thugs. The common man becomes victim of a corrupt and unjust system.

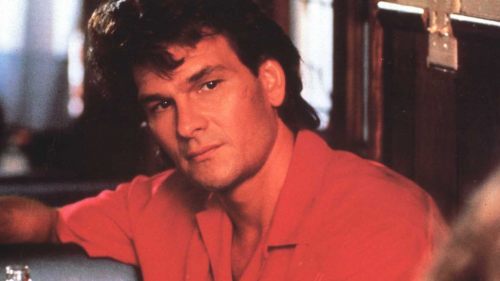

And then a haunted stranger rolls through town, bringing with him a zen disposition and a reluctant proficiency at ripping out throats. Patrick Swayze’s Dalton inspires the townsfolk, beds the local hottie doctor, and uses his funky ninja training to restore order to the system.

Road House is about a community coming together behind a strong leader to reclaim their independence. In this case, rejecting the wealthy elite in favor of the man whose only agenda is to do what’s right. Even if he has to do the right thing a bad way, like ripping out throats.

I didn’t realize it qualified as a modern Western until I was writing my second book. I was considering the concept of the stranger in a new place, which first brought me to Shane, Jack Schaefer’s debut novel, released in 1946 (and adapted into the 1953 film starring Alan Ladd).

It’s one of the great classic Westerns, set in 1889 Wyoming, narrated by the son of a homesteader whose land is being infringed upon by an evil cattle driver. Said cattle driver is causing trouble for the whole town, and there’s not much the law can do about it.

In rides Shane. Like Dalton, Shane has a history of violence he'd rather not revisit. He’s just looking for a little peace, but can’t help stepping up when he’s needed. He saves the day though an act of self-sacrifice and, realizing that he did good a bad way, leaves town.

Road House is essentially a modern retelling of Shane. While it may not be a direct interpretation, in the way John Sturges’ The Magnificent Seven is a remake of Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai, the stories of Shane and James Dalton share a strong spiritual bond.

Shane and Dalton are haunted men and skilled killers. They’re running from histories of violence but discover that not only is violence sometimes the only solution, they’re uniquely suited for the task. And for as much as they try to avoid violence, they’re not trying that hard—Shane still carries his gun, Dalton still works as a cooler. They haven’t completely renounced their ways.

And when the time comes, they step up, because they can, and more than that, they have to. Otherwise, the bad guys win. They’re the heroes Gotham needs, as it were.

Their stories also demonstrate what the Western backdrop is perfect for conveying: Lawlessness, and what happens to men and communities left to their own devices.

The key factor is the rural setting—a place where help is corrupted, cowed, or too far away to arrive in time. Without police officers and judges and attorneys to explain and enforce the letter of the law, you end up with frontier justice.

Nothing happened in Jasper without Brad Wesley signing off and getting a taste. Luke Fletcher wanted to drive people off their land so there was more room for his cattle to graze. The common man has little choice but to accept the status quo.

Along comes the righteous man. Be it Shane, or Dalton, or Sergio Leone’s Man with No Name, or Akira Kurosawa’s Sanjuro. There’s a strong connection thread between the ronin and the gunslinger and the private detective, some of the most enduring character tropes in fiction—and for good reason. We want to believe someone will step up and do the right thing when the right thing is needed. Especially because of how seldom it seems to happen in real life.

These characters, and the Western backdrop, are a fantastic venue to explore themes like community, right versus wrong, and man versus the frontier. It’s how to take the true measure of a man or a woman—strip away the structures of civilization, and force them to apply their own sense of morality.

Once they do, there’s a price to be paid. How far are these characters willing to go, and do their souls remain intact at the end? Are they a ritual sacrifice that polite society requires to function?

It depends. Dalton gets a pass, but Shane’s quest isn’t without consequence.

Both of their stories end with a big showdown. The hero picks through the thugs until there’s a final confrontation with the Big Bad. Both of them get chewed up in the process but ultimately emerge triumphant.

Dalton gets the Hollywood ending: He spares Brad Wesley from a throat-rip, saving his soul in the process. The town rallies to his back, guns down Wesley for him, and protects him by obfuscating the crime. Dalton gets to live happily ever after, presumably to have loads of awkward, uncomfortable sex with Doc Clay.

Shane’s ending is far more melancholy. He saves the day, dispatching Luke Fletcher and his thugs. But in doing so, he takes a bullet, and finds himself across the line he didn’t want to cross. So he rides off, bleeding, and maybe dying, depending on the version (he doesn’t die in the book, maybe dies in the movie, depending on whether you agree with Samuel L. Jackson’s assertion in The Negotiator that “slumped don't mean dead”).

It’s unclear whether Shane leaves because he’s damned, or because it’s a final selfless act, sparing the town from the kind of violence attracted to a person like him. But it seems he does understand a little more about himself, and his place in the world.

The important thing is they’ve both fulfilled their destiny. They’ve restored peace and order and toppled the corrupt system. They did a good thing a bad way. The final question is where that places them on the scale of right and wrong.

That final question might be subjective.

As Rust Cohle put it in True Detective: “The world needs bad men. We keep the other bad men from the door.” Though I prefer the interpretation of Kamala Khan’s Ms. Marvel: “Good isn’t a thing you are. It’s a thing you do.”

Whatever you want to call them—good or bad, gunslingers or ronin, Shane and Dalton are two in a long line of protectors of the downtrodden.