Horror: The Genre That Watches Itself

When you watch a lot of movies in a row, weird things start to happen. As explored by our own Jacob Knight, movie marathons bring to light unexpected recurring themes between films - huge moustaches, for example, or deaths by automobile, and so on. The horror movie marathon I attended recently at Melbourne’s historic Astor Theatre featured a recurring theme that also recurs across the genre, and one that had been nagging at me for a while. Horror, as a genre, is in love with itself.

Every genre has films laden with homage. The mere concept of genre derives from the existence of generic tropes and concepts that repeat across multiple titles. But horror seems uniquely prone to inside references, to the point that there’s an entire subgenre of horror movies about horror movies. And while too many are self-conscious nods to fans by sophomoric filmmakers, others provide intelligent commentary on the genre and its audience.

The most common in-genre homages, of course, are thematic and visual links. Master filmmakers like John Carpenter and David Cronenberg, and writers like H.P. Lovecraft and Stephen King, have had a huge impact not just in their own work, but in the work of others too. Sometimes an idea gets latched onto and developed to the point where the originator’s name becomes an adjective, like with Cronenberg’s body horror or Lovecraft’s unspeakable eldritch concepts. There’s a rich history of horror ideas passing from one generation to the next, through thematic inspiration and even straight-up remakes, and that’s part of what makes the genre so strong today.

But there’s a dark side to homage, where paying tribute to one’s inspirations becomes the raison d’etre of a work (or a filmmaker). I may be in the minority on this, but a recent crop of giallo-inspired horror films have come across to me as empty stylistic exercises with nothing original to add. I’ve seen countless indie horrors at Fantastic Fest and elsewhere that wear their influences on their sleeve, and while in isolation that can be charming, when you see a dozen such films in a row, it’s tedious.

Where is the line between inspiration and fetishisation? At what point is a film less an original work than a fawning list of influences? You get this kind of thing in film school a lot (my film school years made me hate the likes of Pulp Fiction and Requiem For A Dream for this reason): well-meaning filmmakers wanting to emulate and synthesise their heroes’ work in their own, but instead essentially creating fan fiction. It occasionally baffles me that some such films get championed by critics, but then again, you can't blame them for liking a movie if it's designed around other movies they like.

The rise of some tropes in particular has created an intriguing phenomenon in horror films, wherein filmmakers have to decide whether or not their films take place in a world where horror movies exist. Virtually every new movie about vampires, zombies, or werewolves features a scene where characters verbally define the “rules” of that creature, as compared to other films of a similar nature. “It worked in the movie,” say characters in Return of the Living Dead, when decapitation fails to neutralise a zombie. It feels weird for characters to reference other horror movies when horror happens to them; but on the other hand, that’s exactly how we’d respond, were such things to take place in real life. Whether or not other films are referenced in these scenes, the scenes themselves innately exist to place their version of a creature on a cinematic continuum. The only way around it is to pretend horror movies don’t exist within your horror movie - but then everything has to be done in longhand. Among the few times heavy references have truly worked innovatively have been films like Cabin in the Woods or Behind the Mask, which reinvented the source of their horror tropes while playing into them wholeheartedly. It’s a conundrum that doesn’t really exist in any other genre.

Horror also seems particularly plagued by the most basic form of homage: name-checking and in-jokes. How many horror films have you seen where a character attends Carpenter High School, lives on Romero Street, or has a boss called Mr Craven? How many have quoted, via dialogue or visual gags, The Evil Dead or Psycho? There are tons of these movies, particularly today. It was cute in the ‘80s when Night of the Creeps did it; now, it comes across as tacky and juvenile. It dooms otherwise-strong movies to a certain degree of fan filmdom. Would Nightmare on Elm Street have become as iconic if it had been set on Browning Street or Whale Street? What if Friday the 13th had taken place in Camp Black Lagoon? It’s not hard to come up with original (or even ordinary-sounding) names, and it’s definitely easier to watch them. Referential names will never become as iconic as original ones.

Oddly enough, the most successful and thematically interesting branch of meta-horror is also one of the most self-indulgent. I’m not talking about sequels concerning their own production (as has happened to Nightmare on Elm Street, Scream, and Child’s Play, to name a few), nor the increasingly depressing onslaught of horror films about horror fans (i.e. their directors). Rather, I refer to the subgenre of film-within-a-film horror: where horror cinema itself is the source of the scares.

Lots of horror movies feature other horror movies, of course, to help set a tone or to just annoyingly wink at the audience from the background. But some go a step further and create clever links and loops between the film, the film within the film, and even real life. The most satisfying arc in Fright Night is the journey of actor Peter Vincent from non-believing hack to vampire-slaying badass. Demons, The Signal, and The Ring centre around the implication that a visual image is either turning people into killers or killing them outright. The little-seen bizarro masterwork Anguish, arguably the champion of the subgenre, compounds layers upon layers of cinema artifice and vision symbolism to create a surreal mindfuck of a movie. Hell, Michael Jackson's Thriller is all about this stuff too. The sense that images of horror can be so powerful as to effect horror in the real world is incredibly potent.

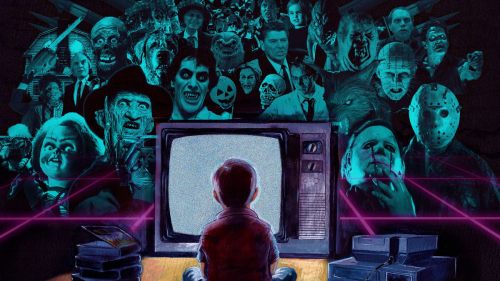

Why does this seem to happen in horror so much more frequently than elsewhere? The answer lies in the nature of horror fandom and of watching horror movies. Horror fans are intense, and many horror fans later turn into horror filmmakers. There’s an evangelical edge to horror fandom that results in a lot of tattoos getting inked and a lot of black T-shirts getting printed. Horror fans stick together, to the point of forming cliques and scenes like Deathwave (whose existence has sparked considerable debate recently). The genre’s status as taboo amplifies that fandom even more; the modern wave's roots in trading of sometimes-banned movies grants a furtive obsession to its adherents. Put simply, horror fans are total nerds, and when horror fans make movies, their films absolutely reflect that.

All of that is added to the fact that one of the situations in which we’re most frequently scared is "while watching horror movies." You’re already at a heightened state of tension while watching horror; the notion that something could fuck you up right then and there is an unnerving premise indeed. In a world where fear is increasingly experienced via Fox News bulletins, multiplex screens, and video games, our reference point for being scared has changed to incorporate moving images at a fundamental level. Horror movies are scary, and for better or worse, horror movies are determined to keep reminding us.