On DIRTY LITTLE BILLY: An Alternative Origin Story For The Old West’s Most Famous Outlaw

Full Disclosure: This movie is fucking impossible to find in good shape. It’s never gotten a proper home video release, so be prepared to watch it in crunchy, compressed, pan-and-scanned glory.

Before the Millennial Generation's scab-picking obsession with outrage and nuance, Baby Boomers had a lock on acting like entitled assholes while actually working to change shit. Counter Culture Cinema, often called The American New Wave, was fertile and hospitable towards the Western, a genre built around personal freedom, inalienable rights and an unwavering sense of conscience. By the late ‘60s and through the ‘70s, the Western had been co-opted so thoroughly by hippies and progressives, they began to border on anarchist, libertarian diatribes about how much stuff sucked. The Alternative Western in its most obvious state is still a Western, after all. Few stories represent the Western better than Billy The Kid’s. He was an original rebel, raging against the machine, The Man, rebelling without a cause or in spite of one, living fast, dying young and all the other platitudes of an immature, sexy, short life. He was the original punk, petulant and snot-nosed. He parlayed his egomania into stardom, a sort of celebrity that every bad boy since has recreated.

“You were a bum in New York and you’re a bum here.”

With those classic bad dad words, William McCarty jammed from his pop’s farmhouse and tin-can-kicked his way into the zeitgeist. Most folks don’t know that, according to expert opinions, Billy was born and raised in New York City. As a young teenager, his mother and father (or more likely stepfather, Mr. McCarty) moved West, and by the time he was fifteen, The Kid was embroiled in cattle and horse rustling, odd thefts and a shooting or two. He went on to become a “regulator” in the Lincoln County War, which led to a certain living canonization as a badass folk warrior, and surely emboldened him to continue his party of gambling, girls and guns. How does a teenage kid from the tenements of Manhattan’s Lower East Side become the most famous outlaw of the Old West? That sounds ripe for one of those Superhero Origin Stories we’re so hot on these days. In the early ‘70s, in the midst of Counter Culture and liberalism, Dirty Little Billy outdid even the best Marvel’s got today.

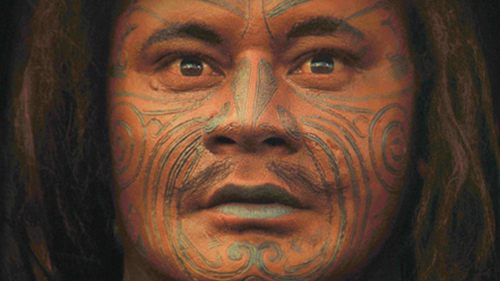

The film plays out with many of the hallmarks we take for granted in current left-of-center cinema, from handheld camera work to a jaunty, rocking score. It has a naturalism that, much like its more famous contemporaries of Peckinpah and Hellman’s work, was surely a shock. There’s blood on the lens, and enough mumbling in dirt and mud to satisfy even the most Wild of the Bunch. Billy himself is a troll, played by Michael J. Pollard, who portrays the icon as if he were Gollum dressed up like a cowboy. He’s landed in the Old West with a Noo Yawk accent and a serious lack of skills. Sitting with boys from the town, they grill him, “Can you hunt? Fish?” He shakes his head and says, “Cards.” He’s a late-sleeping, cigarette-smoking misfit. After getting kicked out of the house for neither shaping up nor shipping out, he takes up in a rival town with Goldie and Berle, a top-hatted rogue pimp and his whore girlfriend who run a lackluster saloon. Goldie’s got crosshairs on him as the town begins to modernize and grow around him, and takes in Billy as an erstwhile gang member. In a drunken, violent, sexually immature way, they form a love triangle that rivals the more wholesome version in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, and their self-destruction has more grime than the romance of Bonnie and Clyde.

The plot is linear, never straying from Billy’s progression over a short period of time, mostly split between his time with Goldie and the pressures of home life, staging him as a classic teenage runaway, a listless brat. Goldie’s greatest gift as mentor to The Kid is teaching him how to shoot, how to fuck and finally, that iconic top hat. The film’s poster proudly proclaims “Billy The Kid was a punk”, easily half a decade before that word meant what we think it means. We watch Billy become The Kid we know and yet he rarely does the right thing. When he does, it’s usually for the wrong reasons.

While they enjoyed gonzo Mad Men mid-‘60s bacchanalia, Stan Dragoti and Charlie Moss lead a revolution in advertising. They would, over the course of their careers, shape how and what we bought, ranging from mufflers to whole cities. These guys came up with “I HEART NEW YORK”. Somewhere during all that, high on amyl nitrate and hubris, they got it in their heads to make movies. Dragoti would eventually go on to make well-known schlock like Love at First Bite, Mr. Mom and The Man With One Red Shoe, all while still shilling rental cars and introducing us to pre-bottled water. He’d go to jail in Germany for cocaine possession while railing against his ex-wife, supermodel Cheryl Tiegs, and eventually sell his ad business for more money than most of us can fathom. Moss never continued to make films like his advertising colleague, but their relationship overlapped on Dirty Little Billy, which he cowrote.

As Dragoti’s life became more and more wild, his story more unfathomably awesome, the film became lost to the annals of low-budget Westerns that were still too common in the ‘60s and ‘70s. The subversiveness of Dirty Little Billy never caught on, and barely got a release, even though it was the second-to-last film Jack Warner produced, just before 1776 and right after Camelot. He’d famously derided Bonnie and Clyde during a pre-release screening, only to see it give birth to the very movement that Dirty Little Billy was part of. It makes you wonder what happened in the last couple years of the ‘60s to lead that 80-something-year-old Jewish studio magnate into the hippy-dippy Old West. Was the film catharsis for a group of filmmakers whose lives and art had been dedicated to pleasing the masses? Was it penance for the toothless consumerism that Dragoti, Moss and Warner sold for so many decades? These guys were businessmen in the streets and outlaws in the sheets, at least for a shining moment when being an insane progressive meant making stuff that might piss off even the few that saw it. That’s surely a charm of this lost film, its Punk ethos being formulated by Company Men, showing us that even squares have to file the edge off every once in a while.