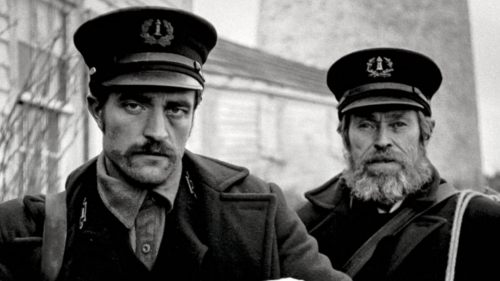

THE WITCH Director Robert Eggers On Black Phillip, Folktales And His Overhyped Film

It was the end of the day when I got to Robert Eggers. He’d been in a hotel room all day, talking to journalist after journalist about a movie that he finished back in 2014, that first screened in 2015 and that is finally getting released in 2016. He was clearly exhausted - both from the final effort of releasing The Witch as well as from sitting around talking to hundreds of journalists, one after another. This is the worst time to get an interview spot, frankly - you’re always talking to a husk of a human being.

But that wasn’t Eggers. He was exhausted for sure, and he apologized if he was repeating himself (answer the same questions all day and your replies become a formless mass to you, just words pouring out without context, so I understood the fear), but he was alive and he was engaged. The Witch is a work of someone who is incredibly detail-oriented, and that personality trait and passion carried him through. I would never have guessed that I was the last person he was talking with that day.

That resilience probably paid off in spades on set. The Witch was shot deep in the Canadian wild, mostly with natural light, far from any sort of big city comfort. It was an intense shoot, one where actors were required to bring incredible, soul-shredding emotion every day. And it had animals, the number two thing you avoid when making a movie (number one is shooting at sea). Yet Eggers made it through and, more than that, flourished. The Witch isn’t just a good movie, it’s a great movie. It would have made my top ten if released last year, and I think it has a real shot this year as well.

With witch movies set in this milieu the standard trope is to keep the supernatural a mystery, or to lean towards hysteria. But you chose to reveal that there is a real witch very, very early in the film. Why?

Growing up in New England we heard about Salem all the time and I just didn’t understand it. I didn’t get how it happened. But when I started doing the research and started reading the first-hand accounts, and realized that the fairy tales and the folktales are the exact same thing as the accounts of ‘real’ witchcraft - that women were being put on trial for giving children poison apples. The real world and the fairy tale world were the exact same thing in that period. When someone was calling you a witch they really believed you were an archetypal, fairy tale ogress capable of doing all the things that happen in my film. That was actually what they were accusing you of, it’s what they believed. When I understood that it’s when I understood how something like Salem could happen. But additionally I realized this could work as a genre film if I could take the audience back to 1630 and get them into the mindset of these English settlers. The witch could have power and be scary again.

The reason why I show the witch so early is because today a witch is a plastic Halloween decoration or Samantha from Bewitched, but people have to know what did a witch mean in the 17th century, and they needed to know what the stakes.

This film is so specific and seems so painstakingly researched. Does research ever get in the way of telling your story? Does it ever close off avenues that you want to explore - “Oh, they would never have done this because it wasn’t invented for 20 more years”?

There are some inaccuracies in the film, but I’m aware of them.

You’re not the kind of person who needs every T crossed?

I want to know if I’m breaking a rule. If I’m actually transporting you into the world, I have to transport you all the way. I don’t think authenticity is the be-all, end-all for filmmaking, but for this film it kind of was the be-all and end-all. But I will say that in order for it to be truly transportive, and for you to feel like you’re truly there, I need to be articulating this like it was my memory of my Puritan childhood. That kind of specificity means the house needs to be made of the correct materials, the clothing needs to be hand-stitched and hand-made and so on and so forth.

However! It’s like, look, we can’t shoot this movie in a house that was actually the size of a house they would have built. It would have been too small and too hard to shoot in. The windows need to be a third bigger so we get more light in. I think one of the biggest inaccuracies is that probably this family wouldn’t have a garret because it would be too difficult to build a garret… if this kind of mode is not what you want, tell me to shut the fuck up.

I love this.

The kind of planks they would need to build that garret, the labor involved - pit sawing them would be crazy, with just William and the boy. Or the cost of going to a frontier lumber mill would have been astronomical. So the garret wouldn’t be there. And even if they had a garret, it would have only been used for storage of tools and foodstuff. The twins would have been sleeping in bed with their parents and Tomasina and Caleb would have been sleeping on the floor by the bed.

But I wanted that Hansel and Gretel moment of them listening to their parents from the garret, so authenticity is trumped by the story.

Your authenticity extends to the language. You have these actors who are getting dialogue that is probably difficult to turn around and deliver naturally.

Because I was in the super fortunate situation of being able to cast whoever I wanted I didn’t have to look for a star to please, please, please help out this poor suffering indie movie. I only cast people who could do it. If you couldn’t do it, I wasn’t interested. The whole movie hinged on it.

Was there rehearsal?

There was a week of rehearsal. I was looking to cast good people, not just good actors because when you’re dealing with really dark subject matter people need to be able to support each other, to trust each other and help each other get out of it. Also the conditions were pretty poor - all the money was on screen, so it wasn’t cushy.

We were working on being a family, trusting each other and creating a safe environment for the child actors as well. The nuts and bolts of it were that we had a very short shoot, with a very demanding blueprint for the cinematic language - it was almost cut in-camera, much to Loiuse Ford, the editor’s, despair - so that meant everyone needed to know this is how you milk the fucking goat! This is how you use farm tools! And just so they knew their blocking so we could make our days.

De Palma once said that coverage is a dirty word to him.

I agree.

How do your actors feel about that?

Cool, man. I think there was a time at the end of the first week when, one day, when Kate (Dickie) and Ralph (Ineson) felt that I was more interested in the blueprint than the performance, which was a big lightning bolt for me. It certainly wasn’t my intention. But I think aside from that day it was cool for them.

Can you talk about threading the supernatural elements through the film? People have some expectations of what they think a witch movie is - were you trying to meet them?

I was trying to do my best interpretation of what I thought a lay family from 1630 in New England might have experienced if their beliefs were real. Reading these accounts, what are the tropes that happen in every story? Those need to be in the film. What are the ones that personally speak to me? They need to be in the film. Then there are the weird, exotic ones where you wonder ‘What the hell is that about?,’ but something about it really works. The ones that are an archetype that is almost lost to us but isn’t quite. Like the hair - hair isn’t as big a deal to us in contemporary American culture, so we don’t think of them, but there’s something really potent about it.

Coming out of Sundance the breakout star of the film has been Black Phillip. Were you expecting the goat to be as popular as he turned out to be?

No. No, man. The funny thing is, when we were editing it - it’s so funny to me that the ad campaign is all goat, goat, goat - I remember investors and producers were saying ‘I don’t think we know the goat is important in the edit.’ And I was like, ‘Good, I don’t want people to know the goat is important! I don’t want people to think about the goat.’ But everyone’s going in thinking about the goat!

That’s how marketing can come at you from a weird direction.

I think it’s okay. Obviously I hate the fact that this film has been so overhyped, but what can you do?

Are you afraid of that?

Of course. I believe in the film, but come on. I’m a crotchety snobby little director bastard, so of course when things are overhyped I’m the first one who is like, ‘Oh whatever, it wasn’t that great.’ I’m sure that’s how I would be with this film.

But it’s interesting how the marketing has gone into the twins and the goat, but in a weird way - for a broader audience - I think it’s good. It gives you more things to latch onto. Because this is such a slow burn, because it is subtle and atmospheric, the marketing creates more narrative things for the mass audience to hang on to and get excited about as they go into the film. I think that might be good… even though for a snobby bastard like me I would want to stay away.

Speaking of the film being a slow burn - very often on the festival circuit the phrase ‘slow burn’ actually means ‘quite boring and nothing ever happens.’ That isn’t The Witch, which has incident strung all throughout it. How did you approach that pacing?

It’s all in the script, really. I just tried to end every scene with a sense of ‘Oh no!’ And that meant each ‘Oh no!’ had to top the last one.

The Witch is hitting at a moment when witchcraft and Satanism are making a big comeback. Do you have any thoughts on why this stuff is hitting the culture again?

My answer will make me sound like a New Age, crystal-worshipping weirdo, so I can’t really get into it, but I will only just say I’m grateful!