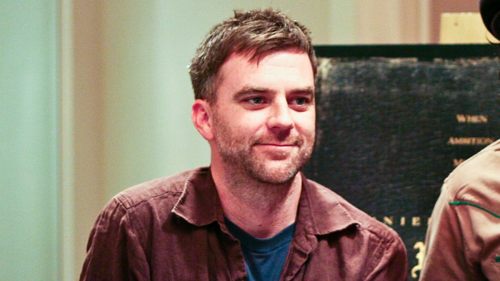

Come Back To Me: The Painful Love Of Paul Thomas Anderson’s THE MASTER

Is this love or pain?

That’s the question being asked by Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master: at what point does intimacy become nothing more than aching? It’s a dull sting; aimed directly at the center of your soul. No matter how much liquor or sex you seek to try and numb this omnipresent niggle that gnaws away at your sanity, the only remedy is its utter antithesis. We seek an unknowable sensation that alleviates loneliness, alienation and despair – one that manifests as either butterflies or a brief, personalized strand of influenza. The only problem is that the remedy can often be indistinguishable from the ailment, as love carries its own brand of paralyzing discomfort.

Over the last decade, Joaquin Phoenix has nobly become an avatar for the broken. Even when playing a towering icon in Johnny Cash, Phoenix discovers the hollow center of the men he portrays and externalizes that emptiness better than any of his current peers (ranking with the Crowned King of Masculine Melancholy, Warren Oates). Though Spike Jonze’s Her is probably the most obvious reference point when discussing the thespian’s mastery of mope (and PTA’s subsequent Inherent Vice as another where Phoenix is quite literally preoccupied by a lost love), The Master’s Freddie Quell is his crowning achievement as a performer.

Hunched over and nursing a spine that seems to barely function, Freddie drinks himself into unconsciousness after coming home from serving his country during WWII. He’s warned by Navy analysts that civilians may not understand the trauma he endured once he steps back onto shore. But Freddie is worse than just a man without a sympathetic country – he’s completely lacking any sense of drive or even the internal compass to right his own psychic voyage. Instead, he’d rather bounce from menial job to menial job; sneaking drinks of secret cocktails he concocts using any sort of rubbing alcohol or paint thinner he can get his paws on. It’s an incredible bit of acting – from Phoenix’s posture, to the way he mumbles instructions to smiling children and husbands, all looking to snap department store portraits for their loving families to frame on walls and desks. Nothing inside of Freddie works outside of his relentless sex drive, and he seems to know it. He’s a primal creature, and Phoenix’s kaleidoscopic gaze (combined with cinematographer Mihai Malaimare Jr. deftly keeping Quell’s surroundings hazy and blurred) lets us know just how loose he is in this new sea of flesh and sin.

It makes sense then that the greatest love of Freddie’s life is discovered during a blackout. Awakening in quarantine on a private ship set to sea, the able-bodied sailor comes face-to-face with a guru who will change his life forever. Lancaster Dodd (Philip Seymour Hoffman) is many things – a writer, a doctor, a nuclear physicist and a theoretical philosopher. However, beyond being a hopelessly inquisitive man, he’s the first human being to engage the drunkard on any sort of nonphysical level, shrewdly asking him to leave his memories at the door before diving into some of the most painful moments of Freddie’s past. It’s immediately clear from the speeches Lancaster gives at his daughter’s wedding (not to mention his wife’s mutterings of unseen conspiracies brewing against the man) that he is a leader to his own private collection of colorful characters. But to Freddie, Lancaster begins as a drinking buddy and ends a witch doctor, forcefully yanking a love experience he’s suppressed via a torturously repetitive “processing” session. Unbeknownst to the “animal” (as Lancaster calls him), Freddie is being purged of this tender burden, only to have another take it’s place; for love and pain are cyclical.

Anderson setting the narrative against a fictionalized backdrop of Scientology’s beginnings has always been a talking point when discussing the picture, but The Master seems more concerned with a bond between men who recognize an unknowable (yet not necessarily identical) spark in one another’s eyes. For Freddie, Lancaster is a purpose – a reason for being. He can create basement libations for the sage that will allow him to feel however he wants – tailor made drunks for a man who is alleviating others’ pain. Watching Lancaster work a room, processing his followers and allowing them to feel connected with their past lives inspires Freddie, as this blessed soul has taken an interest in him. So when outsiders begin to question the monumental work Lancaster is doing, it ignites a fire in Freddie that cannot be extinguished. He becomes a rabid guard dog for Dodd’s Cause, beating down the doors of any who look to insult the “Master” who has stirred up this newfound resolve.

Though the two miscreants may be infatuated with one another, their attraction is anything but healthy. Lancaster is more curious with his new pet than anything else, rescuing the beast and nurturing him to a place of obedience. Lancaster and Freddie are both incredibly dangerous and destructive, but Lancaster’s manipulations are masked by the façade of wanting to “help” poor Freddie; while his wife, Peggy (Amy Adams, acting as a New Age Lady Macbeth), and children, Val (Jesse Plemons) and Elizabeth (Ambyr Childers), struggle to comprehend just what he sees in the ruffian. The answer isn’t so simple, as while Lancaster publicly scolds Freddie for acting out against enemies of the Cause, he’ll wrestle the boy to the lawn in a fit of joy after he’s released from county lockup for unleashing his aggressions. It’s an attraction to power, as Lancaster has discovered someone who will follow him into oblivion.

Quentin Tarantino has often remarked that he considers Paul Thomas Anderson to be his only equal in terms of their generation’s directorial prowess, so it’s not difficult to map a connection between Anderson’s usage of 70mm in The Master and QT’s similarly claustrophobic application of the format in Hateful Eight. Only where Tarantino is interested in creating a gore soaked theatrical playhouse inside of Minnie’s Haberdashery, playing with different planes within the frame and meticulously blocking performances, PTA is instead utilizing the crispness and clarity of the format to present a mystically hazy microcosm. Anderson indulges the widescreen tableaus the larger gauge effortlessly captures (just bathe in the sunlight of those oceanic sequences), but he’s also picking out every imperfection his two leads own with startling clarity. The 70mm format suddenly becomes a microscope, zooming in on these troubled souls as we desperately attempt to decipher just what void each fills for the other. Best of all may by PTA’s love of 70mm sound, as he captures each of Lancaster’s petulant outbursts whenever his belief system is questioned with the same intensity Tarantino does an Old West shotgun blast. Both are totally deafening.

Tragedy is the only true outcome when it comes to this sort of abusive relationship, and the ultimate misstep Lancaster makes is that he actually helps Freddie achieve a semblance of mental clarity. Only this somewhat sober alertness (brought on by allowing himself to fully commit to the Cause’s “healing” devices) clues Freddie in to the fact that his “Master” may be nothing more than a blustery fraud, solely addicted to the adoration of his flock. Fleeing the cult’s embrace, Freddie again proceeds to roam, discovering that the lost love of his past has long since forgotten their adolescent daydreams. Once more he’s drifting through life, hoping to find someone else that will look into his eyes and call him the “bravest boy” they’ve ever met. It’s a reminder that some connections can be so powerful that they forever alter the ways in which we view our personal universe, and fearing that this love can only be found and lost once during this (or any) lifetime may be the most excruciating pain of all.