ScoreKeeper’s Top Ten Film Scores of 2016

Once again it’s that time of year when I reflect upon my three-hundred-and-sixty-five day journey through the jammed-packed jungle of movie music unearthing treasures with each eager footstep. There were so many great scores penned in 2016, and like every year, I fear I’ve missed too many; however, I feel confident that the ones I did experience will forever dwell in my Pantheon of mind-blowing, heart-swelling, and blood-surging favorites.

It seems that my list might be a bit more eclectic than in the past. Hard to tell. I feel like I’m scouring the earth for exemplary examples and I always discover a few in the most unlikely places. There are mega-dollar tentpoles nestled amongst some relatively obscure titles originating from the far-reaching corners of the globe.

As I’m apt to do with this annual article, I hope the words I write serve as an enthusiastic “Thank you,” not just to the artists involved with these ten scores, but rather everybody out there who helped create film music. If you composed, engineered, mixed, recorded, performed, commissioned, or assisted in the creation of scoring a film, then I applaud and thank you for your tireless efforts. I look forward to more great soundtracks in 2017 and will forever be in your debt.

Here’s the list of my top ten favorite film scores of 2017. Enjoy!

10. Nerve by Rob Simonsen

The current retro-synth revival we’re currently swimming in is pretty groovy. Lots of kitschy-cool scores are flocking to harness vintage sounds once banished for simply being too old. The term “dated” has always been (and probably always will be) a four-letter-word that not many want attached to their artistic creations. The results of this revival have been mixed. Pastiche is still largely frowned upon while homage is very much revered. The difference is substantial.

Sometimes composers simply want to celebrate the idiosyncrasies of these aged textures and reprogram how we listen to them by maneuvering them into a modern framework. It’s about the organic balance between old and new ideas, not just artistically but technically as well.

That’s exactly what Rob Simonsen achieved with his luminescent score for Nerve (2016). It’s a flawless amalgam of vintage synthesizers and drum machines recast inside modern dance idioms. What makes this an appealing score from a cinematic perspective, is that the film focuses on the dark side of social media, electronic devices, and the paralyzing grip the entire teenage-tech culture has on our society. While the score certainly captures the technological characteristics permeating the film, it also has a distinct vintage quality to it which broadens the scope of its target audience. This isn’t a film just for teens nor does its story limit the audiences’ relationship to their experiences. This could be anybody at any age wrapped up in the hypnotic squeeze of addictive technology. By diversifying the music slightly, you pull in a larger audience.

This isn’t easy to do under the strict conditions of storytelling. So much of the vintage synth revival relies upon musical choices that could potentially trigger reactions outside the film. This gives rise to inherent obstacles between the audience and the movie itself. With Simonsen’s score, the aural choices sound familiar and retro, yet are assembled in a way as to evoke the music’s stellar innovation. All of these textures are then blended together in a broth of emotion that is fun, invigorating, ebullient, and at times, contrastingly dark and mysterious. It demonstrates a rather audacious approach to underscoring movies. I’m pleased Simonsen had the nerve to accept.

9. The Greasy Strangler by Andrew Hung

Yes, I’m going here. I can’t help but wonder how many of my peers would even consider listening to this score much less place it among such company as to celebrate its merits. The Greasy Strangler (2016) is without a doubt a weird, revolting, yet infectious film that sort-of burrows under your skin in all the bizarre ways you love cinema to burrow under your skin. This bitter and brightly-coloured pill is copiously lubricated by music that might sound pedestrian upon first listen, but like peeling away layers of a rotten onion, brings stinging tears to your inflamed eyes.

Originality isn’t easy to achieve these days, yet I can’t help feel that The Greasy Strangler is one of the more original film scores I’ve heard in a long time. Composer Andrew Hung (of the electronic duo Fuck Buttons) has done a remarkable job yanking off a feat that is in reality, much more difficult than it sounds like it ever should be. It can be a challenge transforming the irreverent and mundane into something palpable and interesting without sounding like your simply pandering to the bizarre. Much like a four-star chef taking celery, chewing gum, grapefruit, pickled herring and vegemite and turning it into an exquisite dish, Hung blends repellent aural ingredients into other-worldly concoctions that are strangely joyous. It tramples upon the principles and standards erected by decades of musical craftsmanship and gives it a big greasy middle finger.

I’ve listened to this soundtrack a lot this year and it’s grown on me like a fungus Lotrimin Ultra can’t cure. It’s odious and a little embarrassing to share with others, but I absolutely adore it.

8. Star Trek Beyond by Michael Giacchino

Michael Giacchino composed four feature film scores in 2016 (Zootopia, Star Trek Beyond, Doctor Strange, and Rogue One: A Star Wars Story) and all of them are exemplars of modern film music for various reasons. Two of his scores really stood out for me and the first to make my list is Star Trek Beyond.

I opine often that the secret to a successful sequel score is to limit reliance upon previous material and use it only when narratively appropriate. This creates the necessary aural space for your film to establish itself a new identity through fresh music. Giacchino’s score for Star Trek Beyond does this to perfection. For starters, it’s more akin to the music from the original television series rather than the previous films. This invigorating approach gives the third film of the franchise an extremely unique identity both musically and tonally.

That’s not to say that previously composed material is not utilized. Quite the contrary! There are plenty of recognizable themes from the first two films; however, they are narratively appropriate and never feel crammed in just to appease the need to put an old theme somewhere. Sequel scores should expand the narrative palette, not water it down as sequel scores are apt to do.

I expected Star Trek Beyond to exhaust the franchise; however, thanks to the clever redressing of Giacchino’s music (and Justin Lin’s distinctive eye), I find myself eager for more.

7. The Nice Guys by John Ottman and David Buckley

Last year I reveled in the stimulating spy-a-riffic sounds of the 1960s pastiche party The Man From U.N.C.L.E (2015) composed by Daniel Pemberton. It infuses everything I love about ‘60s film and television spy music into a brazenly modern score that rocked my world.

This year, John Ottman and David Buckley have accomplished a similar feat by composing a score that perfectly captures the plaid and bell-bottom aesthetics of the 1970s. This period of film music is one of my favorites and it rarely gets the love and attention it deserves. With Ottman and Buckley’s score for The Nice Guys (2016), I feel like '70s scores finally get to be the cool kids at the party again. No more scoffing that cool-jazz trumpet! No more laughing at the wah-wah or snickering at Mr. Rhodes. Hey, solo flute and guitar are doubling together again for the first time decades? Awesome! These guys are all the rage and it’s super-cool to have them back.

As was my admiration for Pemberton’s The Man From U.N.C.L.E. score, Ottman and Buckley’s The Nice Guys manages to create a fresh experience rooted in nostalgia. It doesn’t pander, yet its incredibly nuanced musical characteristics evoke the distinguishable aesthetics of the time period thus elevating a decent movie into one of my favorite cinematic experiences of the year.

6. The Handmaiden by Jo Yeong-wook

Park Chan-wook has always employed beautiful music in his films. It’s a signature characteristic of his particular brand of cinema. He revels in the contrasting dichotomy between darkness and light and frequently pairs them up using music as one of the opposing elements. Composer Jo Yeong-wook has been one of Park’s go-to choices for scoring duties since Saminjo (1997) and always delivers a memorable performance.

Jo’s style is deeply entrenched in orchestral classism giving Park’s films that glossy polish and strong period vibe regardless of when a particular story takes place. At times it may even be difficult to discern which works are originally composed by Jo and which might be pre-existing period pieces cut into the picture. These particular characteristics serve Park’s The Handmaiden extremely well.

Jo’s underscore is a highly sensual bricolage of aural eroticism with saturnine subtexts. It’s beautiful yet hideous. Titillating yet revolting. Evocative yet lucid. All of these paradoxes are bound by music that radiates an opulence that enhances the visual limitations of cinematography without coming off as pretentious or manipulative.

This is an impressive score that should not be underestimated.

5. Doctor Strange by Michael Giacchino

Of all the scores Giacchino composed this year, his off-the-wall melange of strange seems to be just what the doctor ordered. I’ve been critical of Marvel’s approach to film music in the past which makes my connection with Giacchino’s score that much more palpable. I think my favorite thing about this music was my first reaction and I can’t say it was instantaneously pleasant. Instead of an immediate hook-up with my inner fanboy, I recall my initial response was more like, “What?” and “Huh?” and that’s precisely what makes this score so fantastic.

In a time where the McScore is serving billions and billions, it’s a revelation to see a master chef step outside their comfort zone to concoct something wildly pleasing and unforgettable. Giacchino’s score for Doctor Strange (2016) leaps away from the copy-and-paste culture of music creation and manages to conjure up strains so perfectly suited for its film we’re left wondering if it originated in the same dimension. I can’t imagine this music in any other film working for any other character. It is Doctor Strange. The harlequin melodies, harmonies, rhythms, textures, and instrumentation captures the very essence of Dr. Stephen Strange and what’s even more impressive is you can occasionally hear Doctor Strange manipulating the score with his magic.

Giacchino once told me that he doesn’t accept a project unless he has an emotional connection to the material and is allowed to explore that connection musically. This is one of the elements missing from the Marvel cinematic universe. Composers have been dutifully churning out music for these films, but I can’t tell if any of them have a strong emotional connection to their material or were ever allowed to fully explore it. This should be an obvious characteristic of every Marvel film score.

No matter how good he is, Michael Giacchino doesn’t have to score everything. I like that he’s selective and in pursuit of emotionally charged projects. I hope he continues his work on Doctor Strange through subsequent sequels. I’d love to hear him take all this glorious exposition and develop the hell out of it. When he does, I have one humble request…

The harpsichord is awesome. Use it a little more next time.

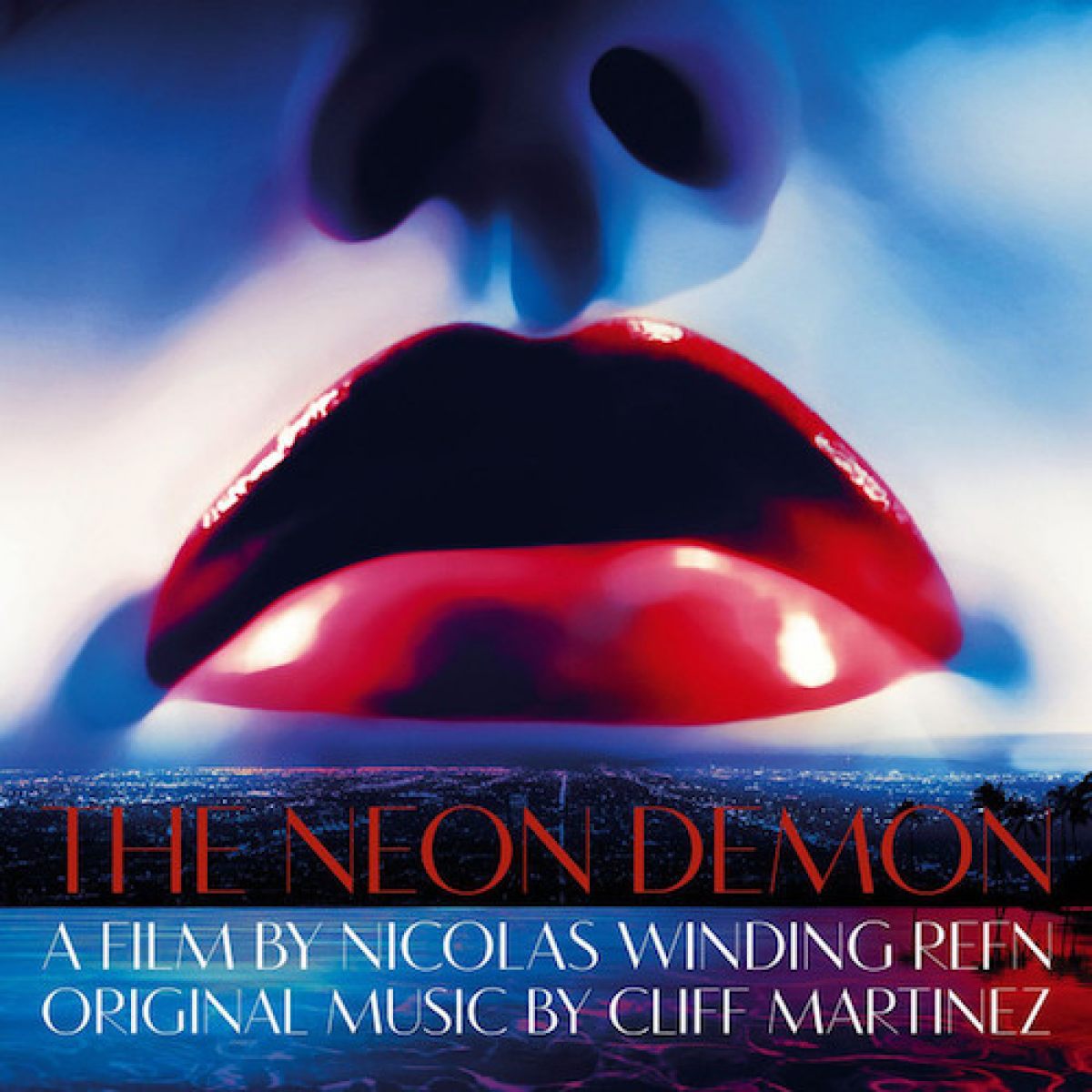

4. The Neon Demon by Cliff Martinez

Since the moment I first saw Nicholas Winding Refn’s The Neon Demon (2016), I had a strong inkling Cliff Martinez’s score would end up in my top five for the year. It certainly gets the award for one of my most listened to scores. There were week-long stretches where I had to listen to it every day. It felt like an addiction.

I penned an extensive review of it last summer published here on this site.

Refn and Martinez are firmly establishing themselves as one of the premiere director/composer tandems in cinema. What I love most about their collaboration is that no two films or scores are ever quite alike. They share similar roots and recognizable aesthetics but their branches always sprout unexpected fruit. Their work demonstrates an artistry in cinema that seems to be fleeting, yet with each film, they catalyze assurance that creativity is alive and well. Martinez continues to impress no matter who he is composing music for, but with Refn, he seems to have found another muse.

3. Kubo and the Two Strings by Dario Marianelli

I’m in awe of this film and its exquisite score by Dario Marianelli. This is one of those movies where I feel blessed just to be alive during the time of its creation. It may be the single most exemplary work of stop-motion in the history of the art form. Let that sink in for a moment.

None of this amazing animation means anything without Marianelli’s meticulously well-crafted score. Like the animators who mold and shape every micro-fractional movement of each character’s performance, Marianelli applies the same skillful degree of nuance with his music.

The ability to make an inanimate object move is not life. Life is emotion and relationships and expression. Without music breathing life into these characters, they’re simply empty shells in search of souls. This is precisely what Marianelli is tasked to do, breathe souls into these characters and when that happens on screen, it’s absolute magic!

2. Assassination Classroom: Graduation by Naoki Sato

Last year Naoki Sato’s score for Assassination Classroom (2015) earned the #2 spot on my list of top ten scores. The film was one of the more delightful and entertaining experiences I had all year. This made me all-the-more eager to see the sequel. I was so excited to see Assassination Classroom: Graduation (2016) that I convinced a few friends who hadn’t seen the first film to join me. Although wickedly fun, Assassination Classroom isn’t narratively complex so I was confident I could walk them through the basics of this delightful “popcorn movie” and fill them in on anything they missed.

That was my mistake.

To my utter surprise, Assassination Classroom: Graduation turned out to be the type of sequel that completely alters the first film by elevating it to levels you never expected. The first film is a wacky, zany, Japanese-manga festival of pure joy. Then the sequel comes along and completely turns that upside-down.

The best analogy I can procure is the effect The Empire Strikes Back (1980) had on Star Wars (1977). The first film was oodles of fun, endearingly campy, and it blew our minds with its pioneering special-effects wizardry; however, even the most die-hard Star Wars fans can admit that its not “arthouse cinema” by any stretch of the imagination. Then The Empire Strikes Back is released and rockets it, along with its predecessor, into a completely different league of cinema.

Although Assassination Classroom: Graduation is tonally different than The Empire Strikes Back, they share the distinction of elevating the overall experience of their predecessors, and both films achieve this in large part with music.

Composer Naoki Sato recreates the same virulent concoction of vitamin F(un) employed in the first film and injects it into the sequel; however, it’s the additional strata of emotion that really expands this film. I was only expecting more of the same wackiness (I was not previously familiar with the manga or animated television series), but what I experienced was so much more emotionally devastating and than what I was expecting. I probably cried during three films this year and Assassination Classroom: Graduation was one of them. I never could have suspected that was going to happen.

I love this score with everything that makes me love film music in the first place. It’s eclectic, unapologetically brimming with emotion, and it completely serves its story. I would pounce on any opportunity to watch this film. Just make sure you see the first one before you do.

1. La Tortue Rouge (The Red Turtle) by Laurent Perez Del Mar

This movie wrecked me. It wholly obliterated me in a beautiful and profound way. Co-produced by Studio Ghibli, The Red Turtle is an animated masterpiece by Michaël Dudok de Wit that does not have a single word of dialogue spoken anywhere throughout the film. The entire narrative is delivered through exquisitely moving art and music. This is a rare picture that belongs nestled away in its own isolated corner of a museum rather than your neighborhood cineplex. It is a work of unparalleled beauty, and the narrative power of its images married to perfection with its music is an exemplar of how much story can be expressed using so few ingredients.

What makes this film so unique is the unabashed simplicity of its moving images. At times the overt stillness of the animation gives the narrative a quality of being told through static photographs. While the animation is unpretentious, yet succulent and arousing, Del Mar’s score elevates it to unexpected emotional heights. Backed by a medium-sized orchestra featuring a female vocalise soaring over its accompaniment, the harmony wrings every drop of emotion from its painted canvas and pulls at your heartstrings in ways that seem impenetrably sincere.

More films like this need to be made. It’s cinematic storytelling in its rawest and most exposed state and I can’t expel it from of my heart (nor would I want to). There were a lot of memorable scores scribed in 2016; however, Laurent Perez Del Mar’s The Red Turtle is my very favorite of the year.