POINT BREAK: Kathryn Bigelow’s Subversive Surf Western

The Fate of the Furious is almost here. Get your tickets now!

“…turn to this green, gentle, and most docile earth; consider them both, the sea and the land; and do you not find a strange analogy to something in yourself? For as this appalling ocean surrounds the verdant land, so in the soul of man there lies one insular Tahiti, full of peace and joy, but encompassed by all the horrors of the half known life. God keep thee! Push not off from that isle, thou canst never return.” — Herman Melville, Moby-Dick

“Thrill-seeking adrenaline addicts have always fascinated me. The idea seems to be that it’s not until you risk your humanness that you feel most human. Not until you risk all awareness do you gain awareness.” — Kathryn Bigelow, Artforum

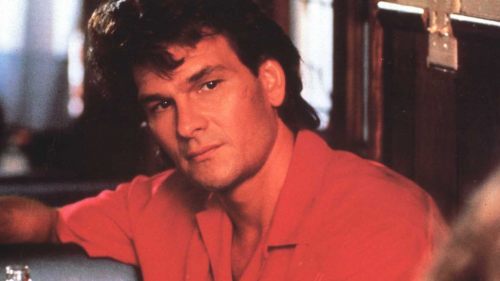

The ocean shimmers behind Point Break’s credits, glowing gold. The words Point and Break cross over, merging and dissolving, and so do the names Patrick Swayze and Keanu Reeves. Patrick Swayze’s Bodhi is a silhouette surfing in slow motion against a soft-blue sea as luminous as a Romantic painting, a mythic figure out of time. Meanwhile, Keanu Reeves’s Johnny Utah loads a shotgun in a gray downpour. He fires at paper targets, and an FBI agent clicks a stopwatch. With this opening sequence, Kathryn Bigelow tells us that the very different worlds of an FBI agent and a surfer will collide, that these two men are destined to meet and to change each other.

Film critics wrongly called Kathryn Bigelow’s Point Break “a dose of macho claptrap” (Sight & Sound) and “intellectually shallow” (The Guardian). But Point Break is a rare, wondrous thing: a fun, smart, sincere action film. It’s a Western, a heist film, a buddy film unafraid of its homoerotic undertones — and overtones. It revolutionized the action genre. You know the story: a former quarterback punk becomes an FBI agent who teams up with Gary Busey to investigate a series of summertime heists. The rookie goes undercover, Lori Petty teaches him how to surf, and he falls in love with zen bank-robbing surfer/agent of chill named Bodhi. It’s a film where you don’t want the good guy to catch the bad guy, where the hero is seduced by an antihero. It’s about falling in love with your dark double, about superego meeting id. It was subversive morally, sexually, and politically.

Co-producer and co-writer Rick King dreamed up the story of Point Break after reading that Los Angeles was the bank-robbery capital of the world. He was taking a surf lesson in Malibu when he thought, “Surfers who rob banks. And a FBI agent that’s a good athlete that goes undercover among those surfers.” King wrote the screenplay with W. Peter Iliff, and Ridley Scott took an interest in directing the film in 1986. In an alternate, hellish timeline, Matthew Broderick played Johnny Utah, and the maybe-not-quite-zen-enough Charlie Sheen was Bodhi, and the film might’ve been called Riders on the Storm. Producers had also considered Johnny Depp, Val Kilmer, even Patrick Swayze for the role of Johnny Utah. But Scott dropped out during pre-production, leaving the project to languish for a few years before Kathryn Bigelow saved it. Bigelow fought for Keanu Reeves to play the film’s protagonist. James Cameron told Premiere’s Johanna Schneller in 2002: “[Bigelow] went to the mat for Keanu Reeves. We had this meeting where the Fox executives were going, ‘Keanu Reeves in an action film? Based on what? Bill & Ted?’ They were being so insulting. But she insisted he could be an action star. This was long before Speed or The Matrix. I didn’t see it either, frankly. I supported her in the meeting, but when we walked out, I was going, ‘Based on what?’ But she worked on his wardrobe, she showed him how to walk, she made him work out. She was his Olympic coach. He should send her a bottle of champagne every year, to thank her.”

Patrick Swayze had already proved he could play sensitive love interests in Ghost (’90) and Dirty Dancing (’87). He had been a throat-ripping ballerina with a PhD in Road House (’89). Keanu Reeves had a softness that his strapping ‘80s-action predecessors Stallone and Schwarzenegger lacked. As Johnny Utah, Reeves taps into the vulnerability of Mel Gibson in Lethal Weapon and Bruce Willis in Die Hard, replacing their wisecracks with sincerity. Reeves’s performance is camp, a parody of machismo that softens as he evolves during the course of the film. It exists in stark contrast to the high-strung masculinity of John C. McGinley’s Ben Harp. This is a film that takes pleasure in showcasing male beauty. Reeves even won an MTV Movie Award for Most Desirable Male for his role that year, and Swayze was nominated.

Point Break reinvented masculinity, abandoning a certain kind of ‘80s machismo, but it also rejected American politics in general. As the Ex-Presidents, Bodhi’s tribe of surfing bank robbers do their best presidential impressions in Reagan, Carter, Nixon, and Johnson masks. Their heist performances are like bad comedy routines: “Please don’t forget to vote!” Reagan reminds everyone during a holdup. Before exiting the bank, Nixon declares, “I am not a crook!” The iconic sequence parodied in Edgar Wright’s Hot Fuzz kicks off with Bodhi in his Ronald Reagan mask using a gas pump as a flamethrower. He torches the getaway car and the entire gas station, then takes off through the homes and backyards of Americans, Johnny in pursuit. Bodhi runs through a kiddie pool, knocks people down, fucks with their laundry, throws someone’s dog. Point Break has something unsubtle to say about Ronald Reagan, and it smartly uses a pulpy story to do it. The film and its characters are suspicious of the entire system. Bodhi reminds his accomplices: “This was never about money for us! It was about us against the system, that system that kills the human spirit. We stand for something. To those dead souls inching along the freeways in their metal coffins, we show them that the human spirit is still alive.”

Underneath Point Break’s radical elements, there’s a coming-of-age story and a romance. Lori Petty’s athletic surfer-chick Tyler is Johnny’s love interest, but so is Bodhi. In a promotional interview, Patrick Swayze said, “rarely do you get a film about two guys that isn’t just slap-ass, macho, jokey crap. And the dynamics were very interesting because I wanted to play it like a love story between two men, which is exactly how it does play.” Much of the dialogue between Bodhi and Johnny feels like double entendre: “I know it’s hard for you, Johnny. I know you want me so bad it’s like acid in your mouth. But not this time.”

Tyler sees through “macho assholes with a death wish.” She finds out the truth about Johnny: he’s an undercover agent, and he lied about his parents dying in a car crash to get close to her. She asks: “Don’t you have a soul?” She challenges him, and she leaves him. Bodhi not only sticks around after discovering Johnny is FBI, he initiates him into his surf tribe in the biggest trust fall of all: skydiving. Johnny pointed a gun at Bodhi, but Johnny is still invited to join him in an act that’s “the closest you’ll ever get to God.”

Ultimately Point Break is about the enlightenment and transformation of Johnny Utah. In an interview with Mark Salisbury for The Guardian, Kathryn Bigelow explained that the ocean “serves as a crucible for the main characters through with they define, test, and challenge themselves.” According to Bodhi, the ocean is where you lose yourself and you find yourself. In Moby-Dick, Herman Melville wrote that what we see in the ocean is “the image of the ungraspable phantom of life.” Whether or not they realize it, all men cherish the same feelings toward the ocean, they are all “water-gazers” drawn to the ocean as if magnetized. The ocean is a new frontier, a new world where Johnny Utah is reborn.

Kathryn Bigelow once referred to Point Break as a “wet Western.” If the cowboy prides himself on conquering new frontiers, on taming the wilderness, the surfer prides himself on giving himself to it, to becoming one with it. At Point Break’s end, Johnny Utah finds Bodhi on an Australian beach where the legendary 50-year storm takes place: “twice a century the ocean lets us know just how small we really are.” Johnny has been hunting Bodhi all this time. It’s their final showdown, and they fight as the storm rages on. Johnny handcuffs Bodhi to him as the authorities arrive. But Johnny decides to let him go, honoring Bodhi’s request to ride one last wave. And the ocean seems bluer with Bodhi in it. Johnny looks at his badge, then throws it into the ocean, a move mirroring Clint Eastwood’s Harry Callaghan tossing his badge in Dirty Harry. But Johnny raises a middle finger figuratively to Harry’s brutal machismo, and to rules, control, law and order. Johnny Utah is not quite ready to give himself over to the 50-year storm, but he’s done with the system. He loses his badge, and he gains a soul.

_500_281_81_s_c1.jpg)