Broad Cinema: THE BAD BATCH And The Rise Of The Female Gaze

From Alice Guy-Blaché to Ava Duvernay, women have been integral to cinema for the last 120 years. Broad Cinema is a new column that will feature women who worked on films that are playing this month at the Alamo Drafthouse. From movie stars to directors, from cinematographers to key grips, Broad Cinema will shine a spotlight on women in every level of motion picture production throughout history.

This week's article is in honor of Ana Lily Amirour's The Bad Batch. Get your tickets here!

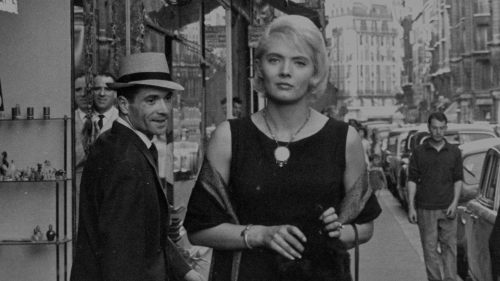

Ever find yourself watching a movie where a female character takes a shower for no good reason, plot-wise? What about one where she climbs up some stairs, the camera sinking down to an angle just right for an upskirt? She might even be clutching a weapon, steadying her resolve as she makes her way toward a confrontation with a hulking serial killer. Our heroine might be trying her best to save her own ass, but we’re busy staring at it. Sure, we might be with her on the stairs, but in that moment we’re clearly not expected to share her experience. The director knows, the cinematographer knows, and we the audience know that she’s just too hot to pass up an opportunity to stare. That’s the effect of the male gaze on film, of course.

The prevalence of male directors makes running into vignettes like these damn near unavoidable in the theater. Naturally, not every man who puts women’s bodies to film does it salaciously. Many simply don’t know what to do with women at all, shuffling them around from mark to mark without much purpose beyond set dressing. Of course, there is definitely a plurality of perspectives among men who direct movies, and both rookies and masters alike are capable of constructing fully fledged female characters with complex motivations, character arcs, and all the good stuff. But out of the 250 top films of last year, 93% of the directors were men, and when you have demographics like that, the odds become greater and greater that boys will be boys. If for no other reason than they simply aren’t exposed to enough diversity of perspective in an industry that homogenous.

Though the number of woman directors may still be shamefully low, 2017 is looking to be a banner year for high-profile female filmmaking. The release of Wonder Woman clearly busted open a nation-wide dialogue about what projects women want to direct, star in, and throw their hard-earned money at. Now that Wonder Woman has raked in nearly quadruple its production budget in worldwide box office sales, the concept of a woman behind the camera is looking more and more bankable all the time. But what are we seeing in terms of the artistic perspective of Patty Jenkins and her fellow female directors? In a development that should shock no one but will invariably fry someone’s brain, it turns out that women filmmakers don’t just see things differently from their male counterparts, but from another as well.

For example, watch Ana Lily Amirpour’s The Bad Batch for about ten minutes and you’ll bear witness to the logical inverse of the male gaze. Amirpour’s focus is unflinching as she leans hard into the film’s central theme: the consumption of human flesh. Yes, there are cannibals in this movie, but what’s more striking is the way her camera simply devours bodies of all kinds. The bass-thumping, iron-pumping, South-Beach-gone-wrong scene that introduces Jason Momoa’s character, Miami Man, is a decidedly gratuitous display of oiled, rippling manflesh. More’s the better for fans of Momoa’s metahuman physique, but the ogling isn’t limited to Miami Man. Suki Waterhouse’s unwilling anti-heroine, Arlen, is served up just as zealously as her male counterpart. Literally at first, as her arm and leg are amputated to feed a band of hard-bodied cannibals, and then more figuratively as Amirpour’s lens feeds us shot after lingering shot of Waterhouse’s trembling lower lip, truncated limbs, and emoji-shorts-clad booty.

Amirpour clearly works very hard to resist a meaningful close reading of these visual feasts in The Bad Batch, with varying degrees of success. Regardless of gender, age, and social standing, none of her characters escape dehumanization, either at the hands of other characters or by the director herself. Everybody is reduced to flesh at one point or another—swollen pregnant bellies, luxury-softened male bodies, waifish models, sun-crisped lunatics, tender children, and jacked lady bodybuilders all get their screen time. Amirpour’s gaze is omnivorously hungry, and so is the nightmarish world of The Bad Batch. We see men eat women, men eat men, women eat women, animals eat people, people eat animals, and children eat anything put in front of them. The camera testifies that regardless of Amirpour’s disdain for attaching prescriptive meaning to her films, she is at least fundamentally attempting to convey that in this world, and perhaps the world at large, meat is meat.

Patty Jenkins clearly took a different tack when she stepped behind the camera for Wonder Woman. From early on in the film, it was clear that under Jenkins’ watch, Diana Prince was certainly not a piece of meat. This is made evident throughout the film in ways that are both direct and subtle, though the deft, blink-and-you’ll-miss-it choices Jenkins makes are the most powerful, bordering on the subliminal. One of the first scenes of the movie finds Diana diving off a cliff and into the ocean after Steve Trevor’s downed airplane. Jenkins’ camera focuses on the plane, where Trevor is trapped, struggling to free himself from his seat as it drags him to a watery grave. Wonder Woman swims into frame, moving quickly toward the helpless soldier. The camera is placed just right for an upskirt here, but Jenkins cuts away just as we’re beginning to think we’ll finally find out if Diana’s underwear is red, white, or gold. If this were nearly any other movie, we would be subjected to at least some butt cheek, but not here. This is a heroic moment, and Diana’s heroism is not undercut by anyone’s desire to get a glimpse of a sculpted Amazon ass.

Not to say that a male director would never have made a similar decision, but Patty Jenkins demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of the way female characters are easily, thoughtlessly, and disastrously undermined by a bit of misplaced objectification. It’s that kind of tonal sensitivity that allowed Wonder Woman to connect with audiences all over the world. Men and boys got the opportunity to watch a female superhero presented in much the same way that her male counterparts are—like a hero, not a prize. And even if women couldn’t quite put their finger on exactly why the movie felt like it was especially for them, they knew intuitively that it was. That’s the power of the female gaze: to allow the audience to focus on what a female character is experiencing by closing the emotional gap created by voyeuristic staging. In other words, Jenkins treated Wonder Woman as a subject, not an object.

Unlike relative rookies like sophomore filmmaker Amirpour and the formerly indie, now impossibly famous Jenkins, veteran director Kathryn Bigelow has been well established in Hollywood for at least a decade. Longer still if you track the rise of her career, as I do, from the brilliant but commercially unsuccessful 1987 release of Near Dark, or from her first box office success, 1991 surf-gang masterpiece Point Break. As the only woman to ever win an Academy Award for Best Director (The Hurt Locker, 2009), Bigelow has achieved rarified status as the kind of filmmaker who, for better or worse, seems to have transcended the cultural obsession with qualifying the title of “director” with the adjective “female.” In-depth editorial profiles on Bigelow praise her work ethic and technical skill with a camera, forgoing descriptions of her appearance and manner in favor of analyzing her striking ability to synthesize current events into compelling, politicized dramas. This kind of normalization and reverence, while disappointingly atypical for women behind the camera, is certainly deserved. As a filmmaker her voice is notably versatile, confidently moving from niche genre exercises to tentpole thrillers with mass appeal.

Her 2012 collaboration with journalist Mark Boal, Zero Dark Thirty, is a solid example of Bigelow’s prowess. The film, a grippingly intense dramatization of the manhunt for Osama Bin Laden in the wake of the September 11 attacks, is singular for its unflinching depiction of the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques—otherwise known as torture. But the most impressive part of Zero Dark Thirty is that it was released just one year and seven months after the raid on Osama Bin Laden’s compound that resulted in his death. Bigelow was already in production on a proto-version of the film’s script when Bin Laden was killed, and she reworked the movie almost from scratch to depict breaking events as they unfolded. That kind of flexibility and sensitivity to cultural relevance is a masterful achievement in and of itself, and it seems that Bigelow is set to do it again with her upcoming film Detroit, a racially charged drama set during Detroit’s 12th Street Riot of 1967. Without spoiling actual historical events for anyone who wants to go into the film cold, the plot centers around the Algiers Motel incident, in which 12 people (most of them black) suffered horrifying injustice at the hands of Detroit police officers.

In light of the rising cultural awareness of the mounting deaths of black civilians at the hands of police officers all over the United States, Bigelow’s timing for Detroit could not be more on the nose. She hasn’t spoken out much on her decision to make this film, but its topical relevance is undeniable. Reaching back into not-too-recent cultural memory to find an incident of racially charged police abuse of power is a shrewd, thoughtful concept on two counts. First, it educates moviegoers about historical events they may have little knowledge of, but clearly ought to. Secondly, it’s a move that allows Bigelow to make a contemporary statement without reopening fresh wounds, such as the shooting of Trayvon Martin, or any number of the mounting list of black victims of police violence. Casting audience favorites John Boyega (The Force Awakens) and Will Poulter (The Revenant) in what will certainly be complex, emotionally charged roles serves to imbue the period setting with an understanding of our own current cultural climate. But that’s Bigelow’s strength. Her perspective is rooted in drawing the connections between people that transcend their time and circumstance.

Certainly these three directors have their own perspectives, as divergent as if they were three filmmakers in any gender combination. And there are certainly more influential voices worth discussing, still unexamined here: Sofia Coppola, Anna Biller, Ava DuVernay, and others. Whether these women step behind the camera with the intention of empowering other women, critiquing society as a whole, or blowing some expensive sets up for summer fun, all of these perspectives have a right to exist on their own merit. There is no official agenda of the female filmmaker, and there is no single, acceptable way to be a director and a woman. That’s the essential beauty of representation.