For All Humankind

That no human being has visited the surface of another world in my lifetime is a deep sadness. As a kid growing up I read and watched SF stories of Mars colonies, of exploration and mining of the asteroid belt, of trips to Saturn and Jupiter and beyond the infinite, and even though that stuff wasn’t actually happening, it felt like it was at least within reach: we’d been to the moon, we had space stations and space shuttles, and President John F Kennedy’s talk of going to the Moon and doing the other, hard, things still resonated as a call to action for a global society willing to look beyond the petty concerns of terrestrial politics. The passing years have only seen a contraction of that ambition: our current outpost in space, the International Space Station, is an engineering, operational and scientific marvel, but one limited to near-Earth orbit and open to political vagaries as the private space industry finds its feet on the path to replacing both the retired Space Shuttle and ageing Russian Soyuz launch vehicles.

Even now, the effort required to fulfil JFK’s determination that the USA should be first to land a man on the Moon is scarcely believable. The Saturn V rocket is still the biggest and most powerful machine ever created, able to fire 47 tons of Apollo capsule, support module, lander, rover and astronaut all the way into lunar orbit, and doing so required not just a whole raft of complex, highly-specialised industries to be created, but whole new technologies to be perfected.

A great deal of this technology is hopelessly, hilariously outdated – the smartphone in your pocket has more than enough processing power to run an entire Apollo mission, let alone the capsule itself – and arguably the safety margins of the entire programme were slim at best, but JFK’s ambition inspired the scientists, engineers and astronauts to power through with the combination of guts, brawn and sheer ingenuity we see in both Philip Kaufman’s The Right Stuff and Ron Howard’s Apollo 13, movies which capture the passion and dedication of the space programme, its engineering intensity and the sheer romance of not just travelling into space, but to the very edge of human experience.

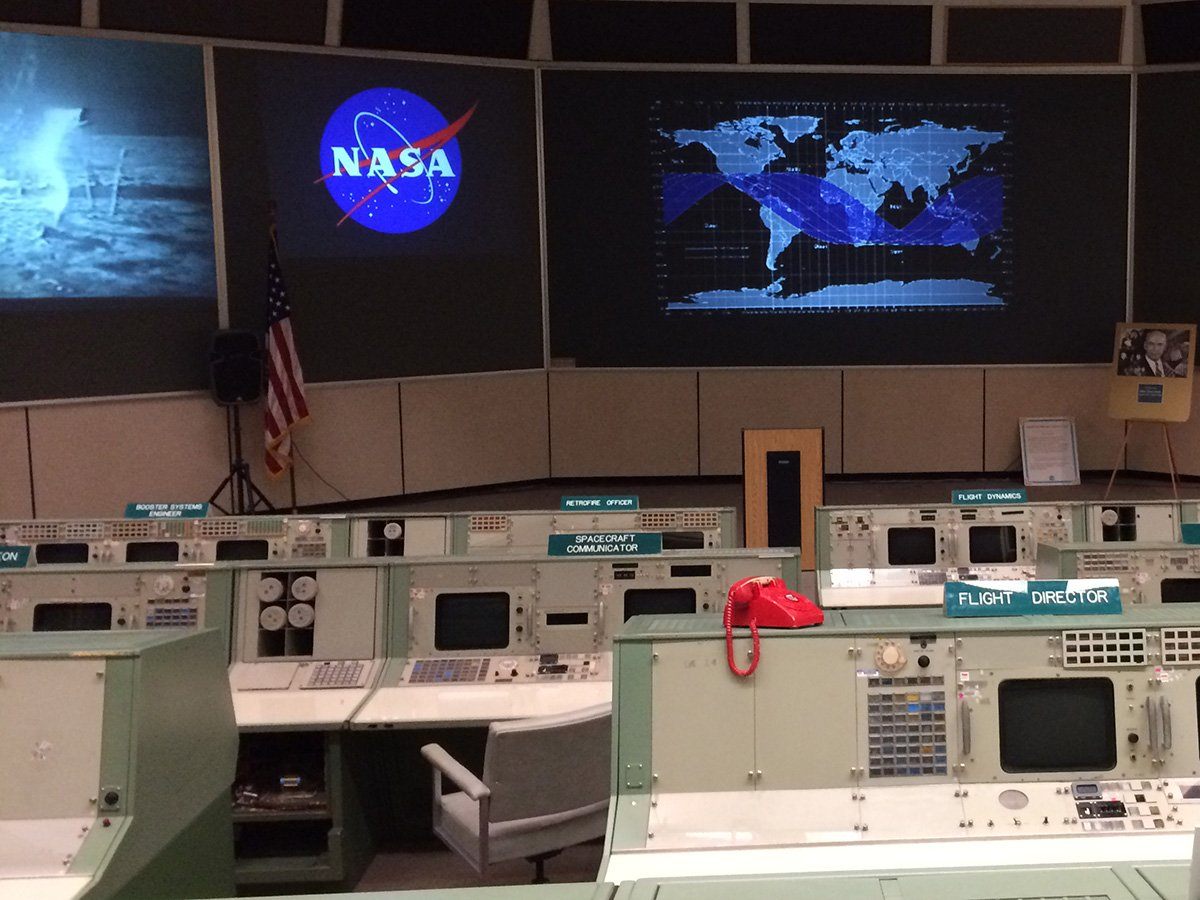

That experience was relayed to Earth via Mission Operation Control Room 2 at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. It was here that Neil Armstrong’s voice rang out from the speakers at 4:18pm on July 20 1969 with four words that confirmed the arrival of men on the Moon: “The Eagle has landed”. At 9:08pm on April 13 1970 those same speakers brought a more ominous message from Apollo 13: “Houston, we’ve had a problem”, setting in train NASA’s finest hours. And it was in this room those missions were brought to a successful conclusion, bringing every Apollo astronaut home safely before serving as Mission Control for the Space Shuttle programme, being designated a National Historic Landmark in 1985 prior to decommissioning in 1995 after a run-of-the-mill mission for Space Shuttle Discovery.

MOCR2 was subsequently reverted to an Apollo-era configuration and now forms one of the centrepieces of Space Center Houston’s Level 9 tour, which offers amazing access to a live space facility along with an opportunity to drink in the history, and there was no way I could pass this up while in Texas for a little film festival you may have heard of.

The tour takes in the Rocket Park’s complete Saturn V – Apollo stack laid on its side, the Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory’s underwater full-size ISS, the neighbouring Space Vehicle Mockup Facility’s dry version along with all sorts of cool experimental space hardware that only drives home how dangerous an environment space is and, most importantly, the Mission Control Center.

First stop is the former MOCR1, now named Flight Control Room 1, formerly home to the overseers of Skylab and now those of the International Space Station. Flanking the familiar map with its track of the ISS’ orbit are screens showing the live feeds from its cameras and control systems, and even though you’re behind the glass of the observation room there’s a palpable tension in being so close to where the action is, knowing that at any moment some problem could flare up and demand the expertise of the people on the other side of the window.

Then it’s onto MOCR2. I may live in a city where thousands of years of history are right there for the touching, where Roman ruins butt up against brutalist architecture and modern roads hem in ancient battlegrounds, but it’s never quite the same as being in a place where the history is made tangible by being almost contemporary, where real events were caught on film or video that’s now burned into our collective consciousness through repeated viewings that render them part of our shared identities, and it takes only the smallest act of imagination to insert ourselves into that historical footage.

That’s what it’s like to walk into Mission Operation Control Room 2, draw up one of those green-backed, four-wheeled government-issue office chairs and sit down at those long banks of push-buttons, dials, knobs, switches and CRT screens which, while they informed the fundamental aesthetic vernacular of SF movies and TV for another fifty years, are the actual hardware used to send people into space and back. Apollo 13 recreated this room in such perfect detail that the movie’s NASA consultant found himself looking for the elevator when leaving the set, but this is the real deal, and when you’re sitting in front of that sign saying “Flight Director” the temptation to punch those buttons, to bark status updates at the CAPCOM, to pick up the red phone to update the White House, is hard to resist.

However, this equipment wasn’t built with longevity in mind, let alone permanent display with people pushing buttons all day. MOCR2 is named on the National Register of Historic Places along with its supporting areas as Historic Mission Control, but the complex is considered as “threatened” due to wear and tear and reduced budgets for its upkeep. The carpet is tired, the seatbacks sagging and there’s a sense of a place which, while fully aware of its importance, hasn’t fully come to terms with its role as a historical display.

With the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 landing approaching Space Center Houston has laid out a plan to create a new visitor centre and restore Historic Mission Control to its exact appearance at the moment of that first Moon landing. The nearby City of Webster in which many Apollo personnel lived during the programme has made a $3.1m gift towards the project and also pledged to match the sum raised by an associated Kickstarter campaign up to $400,000.

With science seemingly under attack in the current political climate, celebrating its achievements can only serve as a reminder of how far it has already brought us, and spur us on towards the future. In 2013 NASA fired up a Saturn-era F-1 rocket booster again, aiming to learn lessons from this 60s technology in order to build a modern, more powerful version to power future missions into space, perhaps to the Moon once again, even Mars and beyond the infinite.

Relatively speaking, the USA is still a young nation and consequently every moment of its history is that bit more precious. Most precious is the history of the entirely new, of achievements wrapped up in the pursuit of the American Dream that defines our conception of the nation, the history that will inspire new generations to better those achievements and reach for the stars once more. It’s not just for them that we need to preserve, promote and teach that history, but for all humankind.

Header image credit NASA. Used with permission.