LIPSTICK UNDER MY BURKHA Review: Daily Indignities, Little Victories

Lipstick Under My Burkha is narratively unique and darkly comedic, though the reason it first entered the spotlight was the meta-narrative surrounding its release. Banned outright by the Indian censors for being “lady oriented” (and a whole host of other reasons), the film now finds itself making waves for its authentic portrayals of the duality of Indian women; from the deep desires of liberation within a rigid society to the secretive adherence therein, reclaiming its own narrative from a repressed and oppressive government that sees its ode to daily struggle as threatening. Its very existence has been made victorious in the process, as has the fact that it reached Indian theatres at all, but let it not be forgotten that its biggest victory lies in its triumph as a work of cinema.

Four women. Four stages of life experience. Four stories tied together by circumstance, and by some boldly conceived narration.

Plabita Borthakur’s Rehana is a teenaged singer caged off from personal expression. She works in her parents’ roadside Burkha boutique, hiding her bedroom posters of American pop stars as she leaves for college hidden from head to toe. By the time she arrives, her burkha lies stuffed away in her backpack and she joins in protests against jeans being banned on campus. Aahana Kumra’s Leela is in her twenties, and her arranged marriage is all but official. She and her secret boyfriend Arshad run a honeymoon photography studio (when they aren’t getting hot-n-heavy in every conceivable corner, including at her involuntary engagement party), clicking pictures of the happy couples they may never get to be. Konkona Sen Sharma plays Shireen Aslam, a married mother of three who works as a door-to-door salesperson in secret. When her husband returns from Saudi every few weeks, her role is reduced to satisfying him in the bedroom, sans protection. And finally, theatre veteran Ratna Pathak as Usha, lovingly referred to only as “Bua-ji” (a paternal aunt) by the kids of the neighborhood. And the younger adults. And people her own age. She’s been widowed for some time, and she’s not even used to saying her own name, but her role as “respectable” matriarch is challenged when she finds herself smitten with a local lifeguard.

The intersection of their stories remains incidental for the most part – as neighbors, they meander in and out of each other’s lives and converge only to commiserate – but the film’s near-constant voiceover weaves a vital thread of commonality. Rather than any sort of exposition or unearthing of individual character, passages from an erotic pulp novel are layered over the film, telling the story of a fifth character, Rosie.

Rosie is never seen or heard. She exists only in a sexual fairytale, caught between men and secret desires. But, given our understanding of the narrative device, the “Rosie” in question becomes any one of the four women at any given moment, their stories reflecting hers through alignment or rebuke as their differing perspectives come to the forefront. Lipstick, for instance, is liberation for some. For Rehana, the teenager who opens the film by smuggling a deep red out of a store lest she be caught buying it, it’s her first step into a discernably “normal” social existence. For Leela, lipstick is a marker of oppression, forced onto her by her mother as she’s dolled up for a simpleton husband, a bloody branding meant to wipe away the shame of being caught during a backroom fuck.

Theft plays an integral role in the lives of these women, whose basic freedoms feel stolen as a matter of normality. Whether or not she has the means, Rehana steals western outfits to avoid her purchases being sussed out, as she molds herself in the image of Miley Cyrus and auditions for a college band. The post-adolescence Cyrus that is, once she began to scandalize the adults who were used to her more “wholesome” image. Leela steals kisses in the shadows. Shireen hustles her way into more privileged homes to make some money on the side. Usha steals glances when she isn’t supposed to, and they all steal drags from cigarettes; an act of rebellion for boys, but a signifier of moral decay when indulged by the fairer sex.

Where Rehana must rob her way to enjoyment, Shireen and Usha’s retail interactions tell their own story. Shireen, who pops morning-after pills like candy since her husband refuses protection, must undergo the Indian indignity of speaking in innuendo to a male shopkeeper, whispering about the dreaded condom (referring to it as a “topi” or “hat”) while 55-year-old Usha, admitting to no one including herself that she’s taking swimming lessons to be touched by the muscular coach, purchases swimwear – a relatively conservative outfit at that – under the pretense of it being for her granddaughter.

These women are by no means the best of friends, but they keep each other’s secrets. They aren’t supposed to be seen at shopping malls, and keep it on the down-low when they spot each other. When either Shireen or Usha end up at Leela’s waxing parlour, a bright pink haven of the kind of in-your-face femininity that would seem trite in the west but is its own form of unspoken rebellion here, they leave their conversations incomplete. Their eyes do all the talking.

Lipstick doesn’t revel in the binary simplicity of its initial setup. Be it Rehana, Leela, Shireen or Usha, women stand in their path just as much as men, though the former are afforded the kind of complexity that speaks to the nature of their complicity. Rehana, once the target of the college “cool girl,” catches the eye of drummer Dhruv for being the only girl in Bhopal who listens to Zeppelin. However Dhruv, her outlet to normalized relationships and sexuality, has his own baggage when it comes to said "cool girl” and how he treats her. Leela, whose arranged marriage subplot is likely familiar even to Western audiences by now, begins to see the previously unseen shades of her mother’s life that have led her to being placed in this position. Her rebellion, sexual or otherwise, doesn’t exist in a vacuum.

What was likely most threatening to the Indian censors is what makes Lipstick shine. Its portrayal of the varying sex lives and sexual energies of these women places them in direct contrast to one another, perhaps more than anything else in the film. The mostly burkha-clad Rehana longs to let loose in the form of dance, and once she’s shamed for doing so in public, she writhes in her bedroom like an emerging butterfly, scored by nothing but silence. The mere act of being perceived as sexual without even having sex, whether through wearing jeans or letting her hair flow or being in a new relationship with someone other than a carefully chosen husband, is her liberation. For Leela on the other hand, a woman who’s managed to smuggle an active sex life into her routine, things aren’t so simple now that she’s begun to see the bigger socio-economic picture that’s forced her into this arranged predicament. For Shireen, a successful saleswoman who can neither sell her husband on condoms nor on the idea of her employment, sex is a painful chore. She exists only as sexualized, her other skills and qualities pushed aside, her pleasure not even considered. And for Usha, any semblance of sexuality is considered something long past, and entirely forbidden. Something pursued under the pretense of visiting a temple. Something only read about in secret, and something only had over the phone under the guise of anonymity.

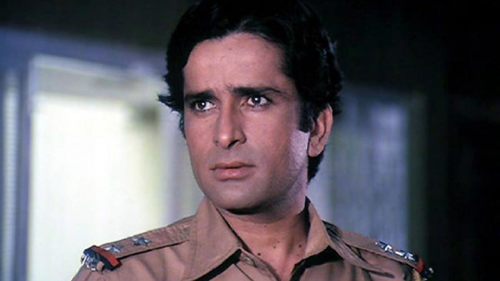

Sex is what separates these women, but it’s also exactly what binds them. When their stories are viewed within a continuum of male society, there is no stage of womanhood during which sexuality is deemed acceptable. Too young. Too old. Too Married or enaged. Widowed. Daughterly. Motherly. Grandmotherly. While Leela’s and Rehana’s relationships are both interfaith (Muslims and Hindus getting together is still an issue for many), these cultural boundaries are never brought up explicitly; rather, the patriarchal forces at play end up transcending them. Regardless of specifics, they all boil down to the same control of feminity at the hands of men, who dictate when and where women are allowed to be sexual beings: the bedroom, after marriage. The men, while recognizably human (the great Sushant Singh brings a hardened stoicism to Rahim Aslam), are not afforded redemption the way the women antagonists are. Lipstick Under My Burkha is a grey film insomuch as it portrays the complexity of downtrodden existence and the women who inadvertently perpetuate it, but it has no qualms about hanging its men out to dry, and nor should it. It sacrifices no realism when it chooses to be black & white about from where the oppression stems.

The film rarely slows down, but its rapturous mile-a-minute comedy allows for its quieter, more considered moments to truly breathe, be it Konkona Sen Sharma’s resilient silence as Shireen eats the chocolate cake her husband rejected, or Ratna Pathak’s paranoia giving way to an unburdened smile as Usha floats in the water in the arms of her secret suitor, standing on the precipice of a second sexual awakening. It’s a film rife with great performances, and a camera that obscures explicit sexual imagery (a smart move in an era of increased censorship) in lieu of faces. Every curious smile, every painful tear, every strand of hair falling out of place and every O-shapen mouth gets its due, as writer-director Alankrita Srivastava crafts a tale of commonality of circumstance within diversity of experience that’s a treat on every end of the cinematic spectrum.

The film’s alternate title, Lipstick Waale Sapne (or “Dreams of Lipstick”), is also the title of the fictional erotic novel from which it draws its narration. And like the pulpy paperback that pops up in the film, a piece of art dismissed as over-sexualized trash, it may not offer all the answers or some ultimate victory for its entrapped women, but it’s enough to help celebrate scattered moments of joy and rebellion amidst dreams of something better.

Lipstick Under My Burkha is currently playing in Indian cinemas. There’s no word on an international release yet, but be sure to keep an eye out.