Goodbye, Tobe Hooper: Cinematic Madman (1943 - 2017)

“[The Texas Chain Saw Massacre] looked like someone stole a camera and started killing people. It had a wild, feral energy that I had never seen before, with none of the cultural Band-Aids that soften things. It wasn’t nice, not nice at all. I was scared shitless.” – Wes Craven (via Jason Zinoman’s Shock Value)

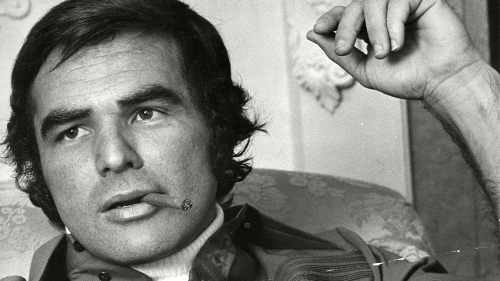

Before producer Bill Parsley was out raising funds for The Texas Chain Saw Massacre as a means to impress waitress/future star Marilyn Burns, Tobe Hooper was in a hospital, watching a man die. Hooper was shooting footage in an emergency room whilst trying to cobble together a documentary on a prominent Texas physician when his camera stumbled upon a gunshot victim. While the man struggled to breathe on a stretcher, gasping his final instances of life, Hooper zoomed in and captured the anonymous death rattle via celluloid. Later that night, the aspiring filmmaker went out with some friends, talked about the experience, and didn’t watch the footage until the next day, when it made him vomit behind the monitor. It was then that Hooper recognized the power of mortality, and how death can completely devastate an audience member under the correct circumstances.

Hooper’s first feature was a psychedelic commune trip that doubled as a thesis statement regarding a drugged out generation protesting the Vietnam War. Eggshells (’69) was a total failure, commercially speaking, but it led to a friendship between the University of Texas dropout and his lead actor, Kim Henkel. The two watched old Universal monster movies together (which Hooper had been obsessed with since a child, where he’d recreate his own versions on 8mm), as well as George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (’68). A product of various small Texas towns, Hooper and Henkel came up with the notion of “nightmare syntax”: wanting to let their story unfold like an inescapable reverie that was equal parts Brothers Grimm, and a down home take on their favorite fiends (with a touch of Manson thrown in for good measure). They were fixated on the idea of an inescapable house in the middle of the Texas countryside, and having known quite a few rednecks during their day, didn’t find the idea of a monstrous familial unit devouring outsiders too far removed from reality.

Parsley met Hooper and Henkel through mutual associates at the Texas Governor’s Office, and the two artists provided the moneyman (who owned the final product 50/50 with the creatives via a shell company, M.A.B.*) a script called Head Cheese. The rest is history, as they say, with Texas Chain Saw going on to become the primal scream of ‘Nam-era pulp existentialism that redefined genre filmmaking from that moment forward. Shot during the sweltering summer of ’73, much has been made about Chain Saw, to the point that there isn’t a whole lot left to be said about the serial killer odyssey (for one of the absolute best takes, I’d recommend our own Phil Nobile Jr.’s 40th Birthday retrospective). The financiers set up multiple buyers’ screenings, inviting big studios like Columbia and exploitation houses like Roger Corman’s American International Pictures. In the end, the high bidder was Bryanston Distributing (for a whopping $225,000) – best known for making a mint on porn blockbuster Deep Throat (’72), and reportedly run by a gaggle of Sicilian thugs just looking to earn another quick buck on the 42nd Street market. Today, Texas Chain Saw has a print stored in the Library of Congress, simply because its considered such a monumental achievement in the overall cinematic realm.

Texas Chain Saw broke its director somewhat, as he chased that same horror dragon while simultaneously waging epic battles against substance addiction (the man certainly enjoyed him some white powder). After delivering his equivalent of a Tennessee Williams hot house melodrama (featuring a killer crocodile, of course) in Eaten Alive (’76), Hooper spent much of the 70s and early 80s getting fired or replaced on multiple projects, most notably the Billy Devane/laser beam-shooting creature feature, The Dark (’79), and the Klaus Kinski/Oliver Reed home invasion picture Venom (’81)(which has been best described to me by filmmaker John Portanova as “Die Hard, but where an actual black mamba plays John McClane”). In-between these trials, Hooper also helmed the greatest Stephen King adaptation for the small screen in Salem’s Lot (’79), a three-hour Movie of the Week opus that scarred numerous childhoods.

This writer had the opportunity to interview Hooper years ago (for a site that’s sadly no longer with us, or you’d be provided a link), and found him incredibly warm, courteous, and open to honestly discuss his career. Hooper’s only request was “just don’t ask me about Poltergeist (’82), man”, delivered with the cadence of a down home stoner. His role in filming the Steven Spielberg-produced scare classic has long been ambiguous, even though he’s still credited as the director once the house lights come up. Regardless of how much or little he shot, there’s still a mean-spiritedness to that movie that thematically links it with the rest of his filmography, as it again deals with strife and deconstruction within the American familial unit. His influence pervaded that set like an open wound, unready to allow its blockbuster producer to deliver a product that didn’t contain his venomous genre instincts.

The oddities dotting the rest of Hooper’s resume are a collection of curios all owning a singular stamp of filmic madness. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre 2 (’86) is one of the most bizarre sequels ever committed to celluloid, chock full of pitch black humor and a supporting performance from Dennis Hopper that concludes with a literal chainsaw dual. Hooper’s Cannon Films space vampire rampage through London, Lifeforce (’85), feels like the result of a literal astronaut on acid. The Mangler (’95) is one of the goofiest King adaptations, bringing a marauding industrial laundry machine into numerous horror fans’ homes via VHS. He helmed an S&M cult movie starring Robert Englund with Night Terrors (’93), and an anthology segment in John Carpenter’s doomed cable pilot-cum-feature, Body Bags (’93). Even his later DTV work like The Toolbox Murders (’04) remake is a legitimately diverting trash slasher showcasing an unsettling quantity of brutal gore.

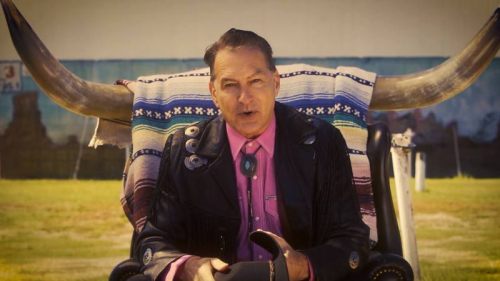

Tobe Hooper died today from natural causes at the age of seventy-four. While he may have devolved into a schlock auteur, with one micro-budgeted feature, he became a legendary maverick. Hooper was a kind soul, speaking with the tenor of a loving uncle who’d sneak out back and smoke a joint with you at sixteen. He and his contributions to cinema will be sorely missed, but preserved forever for future generations to use as nightmare fuel.

*Marilyn A. Burns.