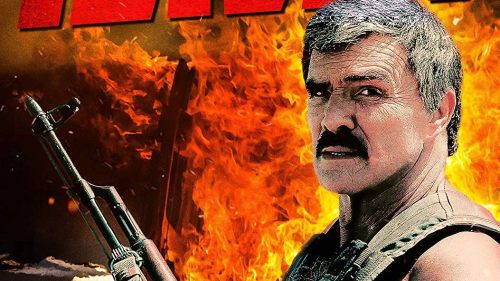

Bandit Out: Remembering Burt Reynolds (1936 - 2018)

"My movies were the kind they show in prisons and on airplanes, because nobody could leave."

Burt Reynolds was a “good ol' boy” in the most elemental sense: the Michigan-born, Florida-raised rowdy offspring of a police chief, he gave up a promising football career following a string of injuries and wandered into the theater program because, well, that’s where all the pretty girls were. Ruggedly handsome and sporting a macho demeanor that drew Brando comparisons and actually hindered his early career somewhat, Reynolds studied to be a stage actor with Wynn Handman at New York's American Place Theater, his critics often writing him off as a buff wannabe (though Burt always claimed the legendary Streetcar actor was "curious" about the Southern kid’s presence).

For over a decade, Reynolds worked as a sort of TV journeyman, landing bit parts in Westerns such as Johnny Ringo and the Navy pilots serial The Blue Angels before scoring a recurring role as the "half-breed" Quint in Gunsmoke. Despite hailing from Scottish and Dutch heritage, due to his olive skin and black hair, Reynolds was often cast in Native American roles, such as the titular Iroquois investigator on Hawk (though Burt noted on more than one occasion that Cherokee blood pumped through his veins). Throughout this era, the actor earned a notorious reputation as a hard-drinking playboy, infamously explaining, "when I'm with one woman, I'm a one-woman man. Period. But when I'm in-between relationships, I'm carnivorous."

Reynolds' appetite was momentarily satiated once he met talk show dame Dinah Shore in 1970. By this point, Burt had nabbed a big screen starring role in Spaghetti Western maestro Sergio Corbucci's Navajo Joe ('66), and subsequently appeared in 100 Rifles ('69), Impasse ('69), and Skullduggery ('70). Though he was 35 and she was 52 – an age discrepancy pounced upon by the tabloids – Reynolds and Shore embarked on a passionate affair that lasted the next half-decade. The couple dreamed of building a house in Hawaii together but, after Dinah refused to marry him, Burt broke the romance off with the melodramatic proclamation, "I will love you all my life. The hardest part is that I’m falling deeper in love with you every moment.” Then he turned and walked out the door. After Shore passed in 1994 (due to complications from ovarian cancer), Reynolds returned to her grave every year to place a wreath on the final resting place of the Tennessee woman he loved and lost.

While he was with Shore, Reynolds cemented himself as one of America's premier movie stars, appearing in John Boorman's Deliverance ('72), the moonshine-running car picture White Lightning ('73), and Robert Aldrich's smash prison football programmer, The Longest Yard ('74). Burt credited a large amount of his success to his relationship with the gab queen, as she'd introduced him to everyone from Frank Sinatra to Orson Welles. Unfortunately, Reynolds also committed near career suicide by posing rakishly on a bearskin rug as the first male (mostly) nude centerfold in Cosmopolitan magazine – a choice he detailed in his memoir But Enough About Me as "one of the biggest mistakes [he] ever made."

No matter how intensely Burt Reynolds loved women, the strongest relationship of his life was with a stuntman. Hal Needham was the son of an Arkansas sharecropper who – after serving two years in the army out of Fort Bragg, North Carolina – decided to head West and throw himself off horses. It was here, on the sets of these serials, that Hal Needham and Burt Reynolds began a friendship that would last the rest of their lives. Since his earliest days on Riverboat, Reynolds was always drawn to the "jock" performers, who stood in whenever the aerobatics became too dangerous (which, for Burt, admittedly wasn't often), and Needham fit the bill of a rough and tumble Southern scrapper whom he wanted to drink a beer with after wrapping a day of shooting. The two became inseparable, and even moved in together, holding down a legendary bachelor pad that had mirrors on the ceiling and fancy tile in the bathrooms (Reynolds’ favorite interior design choice).

When Hal wanted to make the leap from body double to filmmaker – scribbling a script about bootlegging Coors while on location in his home state shooting White Lightning – nobody in Hollywood trusted him to do the job. It wasn't until Burt agreed to star in the pet project his "roomie" cooked up that Universal bankrolled the action/comedy, which co-starred oddballs such as comedian Jackie Gleason and Phantom of the Paradise ('74) pop genius Paul Williams. Regardless of it tanking with critics, the resulting romp Smokey and the Bandit ('77) was a massive financial success, to the tune of $300 million worldwide. Together, the duo became a box office sensation, crafting a string of car chase pictures, such as Smokey and the Bandit II ('80), The Cannonball Run ('81) and Stroker Ace ('83), along with the meta-textual Hooper ('78), where Reynolds essentially played the title character as an homage to his best friend.

During the Needham days, Reynolds carried on an affair with the woman that he would later label “the great love of his life." Sally Field was a TV actress best known for her work on the late '60s sitcom The Flying Nun, whom Burt handpicked to be in Smokey and the Bandit (despite the studio's objection that she wasn't "sexy" enough). The two began dating, and Field appeared in Hooper, Reynolds' second feature directorial effort – the dark comedy The End ('78) – and Smokey and the Bandit II before the two broke up in 1980. Looking back at their split, Burt commented that he couldn't believe he was "so stupid" as to let her go: "you find the perfect person, and then you do everything you can to screw it up.” This heartbreak became another running theme in the star’s rather complicated personal existence.

The '80s saw Burt moving away from the good ol' boy typecasting that'd made him illustrious, opting instead to portray beefy tough guys. Starting with a trio of Dan August TV Movies (all made in '80) – The Trouble With Women, The Jealousy Factor and Murder, My Friend – Reynolds discovered a new type he could embrace with startling ease: the strong, stern man of action. His third (and arguably best) feature directorial effort Sharky's Machine ('81) cast him as a hard-nosed vice cop, investigating a conspiracy involving an Atlanta gubernatorial candidate and a high class hooker (Rachel Ward). Stick ('85) saw Reynolds stepping into the shoes of one of Elmore Leonard's trademark ex-cons, getting caught up in a drug running scheme, while Malone ('87) cast him as an ex-CIA hitman taking on a town run by mercenaries (headed by Cliff Robertson). Heat ('86) let Burt chew scenery thanks to a seedy neo noir William Goldman screenplay, as his sad sack Vegas bodyguard sets out to right wrongs perpetrated on his prostitute friend (Karen Young) by a sociopathic prince.

In-between these brooding brutes, Burt toggled back to the playful charisma he'd exploited on talk shows throughout the '70s as a means to mint himself as a marquee idol, mostly to mixed results. The Best Little Whorehouse In Texas ('82) teamed him with Dolly Parton – a performer Reynolds labeled his “kindred spirit” – as a sheriff trying to keep his favorite brothel alive. Blake Edwards' The Man Who Loved Women ('83) saw him experiencing a bout of all-encompassing impotence as once promiscuous sculptor David Fowler. In City Heat ('84) he joined forces with Clint Eastwood in a period comedic noir where the duo reluctantly solve a murder together. When combined with the Needham pictures, the '80s became a rather madcap decade where Reynolds zigged and zagged unexpectedly, sometimes to audiences' chagrin.

Unfortunately, despite his workaholic nature, Burt accumulated a bit of a shitty rep on sets, taking his personal stunt work a bit too far and getting smacked in the face on City Heat with a metal chair while filming a fight scene. The blow pulverized his jawbone and relegated him to a liquid diet for the remainder of the shoot, causing him to lose thirty pounds (and look quite sickly in Stick) before developing an addiction to painkillers (which his second wife, Loni Anderson, blamed for his alleged domestic abuse during their messy divorce). During the production of Heat, Burt punched director Dick Richards for a perceived insult, costing him $500,000 in settlement money (not to mention the little remaining shine his star had by the mid-80s, thanks to dwindling box office returns). When combined with his ill-advised business ventures – including a regional restaurant chain called Po' Folks – purchase of a private helicopter and jet (not to mention the two pilots making $100,000 each to be on call at all times), and estates in Florida, Arkansas, Georgia, North Carolina, and Beverly Hills, he'd accumulated millions of dollars in debt by the end of the '80s. Suddenly, the man who used to make $10 million a year was in dire financial straits.

The '90s weren't a whole lot kinder to Burt, which saw him mostly retreating to television for comedic series such as the Rockwellian alien sitcom Out of This World and Evening Shade, where he played a former pro football player who returns to his tiny Southern hometown (earning Reynolds two Golden Globe nods and a win in ’92 for Best Performance by an Actor in a Television Series - Comedy or Musical). Between 1995 and 1996, his career completely bottomed out with the low rent horror picture The Maddening ('95) – where he plays a sort of psycho version of himself – and the Demi Moore nudie lark Striptease ('96). However, thanks to Paul Thomas Anderson's breakout San Fernando Valley chronicle of the ‘70s porn industry Boogie Nights ('97), Reynolds' cultural relevance spiked yet again, thanks to his turn as smut auteur Jack Horner.

In yet another poor career decision, Burt decided to turn his back on that masterpiece, publicly stating that he was proud of the work he did on the picture, but that he was somewhat ashamed of the film as a whole, due to his perception that it glamorized the XXX business. For that reason, he declined to help promote Boogie Nights, alienating himself from the Hollywood establishment as it was ready to embrace him with open arms once again. Despite earning an Academy Award nomination and winning the Golden Globe for Best Supporting Actor, Burt's "comeback" really only resulted in a string of little watched indie movies that never made much more of a splash. The aughts were an utterly unremarkable time for the once brilliant icon, who mostly faded away into obscurity, only to be trotted out in forgettable larks such as the Adam Sandler-starring remake of The Longest Yard ('05) where he played the inmates' coach instead of their quarterback.

However, his shunning of Boogie Nights might actually be the greatest encapsulation of the walking, talking paradox that was Burt Reynolds. Nobody was going to tell him what to do. Not his lovers. Not his fans. Not his critics. He was going to dictate his own destiny, for good or for ill. Right up until his passing yesterday – of a heart attack at his Jupiter, Florida home – he continued to teach acting classes and was even set to take a part in Quentin Tarantino’s upcoming “Summer of ‘69” chronicle, Once Upon A Time In Hollywood (as crazy coot and Charles Manson compadre, George Spahn). Despite his many failings as both a movie star and human being, which he readily owned up to in interviews and his own book, there were little regrets in Burt’s life, which might be his greatest accomplishment. You try living out your days in such wild and wooly fashion and see if you can say the same thing at 82.

Though it's admittedly a flawed film, Adam Rifkin's The Last Movie Star ('17) - along with Jesse Moss' chronicle of the making of Smokey, The Bandit - allowed Burt (who is essentially playing himself as washed up movie star Vic Edwards) to say goodbye to his admirers in bittersweet fashion one last time via a fictional lifetime achievement award speech:

"Unfortunately, until today, the last time I apologized for anything was in 1977. I punched out a director on the set of Horsepower. Well, I'm sorry. I'm sorry for being such an asshole... I thought I was too good for this little film festival. Turns out, it's too good for the likes of me. Winning this lifetime achievement award has forced me to examine an important question that I've avoided for as long as possible: what did I really achieve in this lifetime? Most of the movies I've made, everybody knew how they were going to end, right from the first scene. Life's kinda like that: everybody knows how it ends. But it's the scenes in the middle that make it count. A great producer once told me, "an audience will forgive a shitty Act II if you can wow them in Act III." Well, I had a hell of an Act I, a pretty shitty Act II, and I screwed up most of Act III. I made certain of that, but thanks to you...you helped me to see that it's not too late for my Hollywood Ending. And so, with humility and pride and deep appreciation, I humbly accept this lifetime (so far) achievement award, and I'm gonna make sure the rest of my life lives up to the honor of this. Thank you."

No Burt, thank you. Like all of our heroes, you were a beautiful, complex, flawed human being. You touched many lives, and your legacy is one that will live on long after the dust settles in the wake of your Trans Am roaring down life's dirt road. But for now, I simply leave you with nothing more than a final "Bandit Out".