Collins’ Crypt: When Dean Koontz Visited Tobe Hooper’s FUNHOUSE

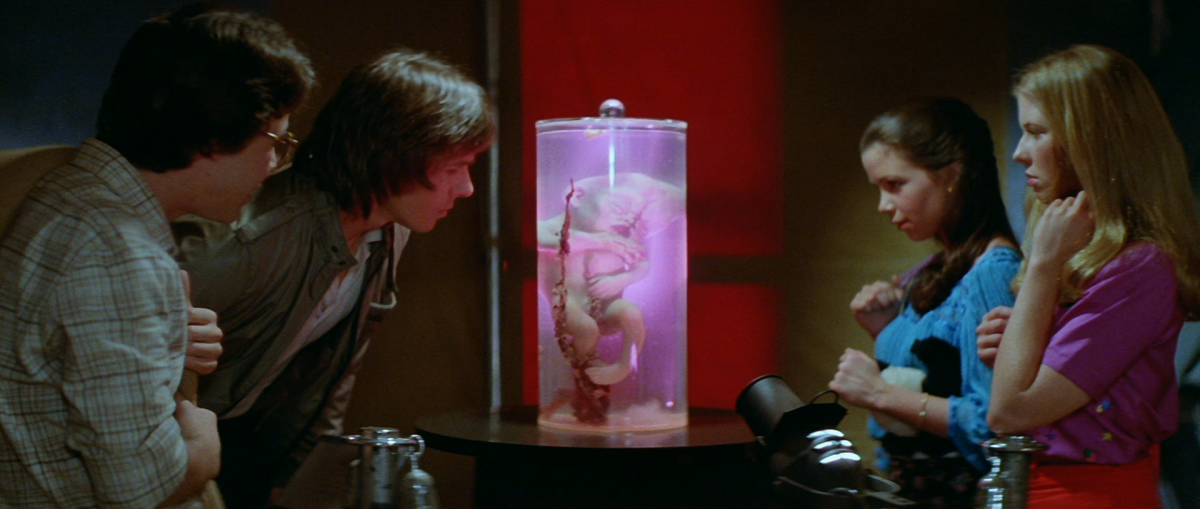

When Tobe Hooper passed away last month, there were the expected tributes to his most famous films like Texas Chain Saw Massacre and Poltergeist, but for an underrated filmmaker it was appropriate to give some love to his lesser known films, such as his Cannon trilogy (Invaders From Mars, Lifeforce, and TCM 2) and his Toolbox Murders remake that was a huge improvement on the original. But only a few highlighted The Funhouse, one of his rare major studio projects, and one that is similarly overlooked in the slasher canon. Released in 1981, it hasn't gained as large of a fanbase as some of that year's other original slashers such as My Bloody Valentine, The Burning, and Just Before Dawn, though that could be due to the fact that it doesn't QUITE check those "dead teenager" boxes off as well as its competition. It's only in the last 15-20 minutes that it really starts to take on a slasher movie feel, as Hooper (and screenwriter Larry Block) opt to spend time with the characters, establish the general unpleasantness of the carnival (and home) atmosphere, and delay the "Uh oh we are trapped in the funhouse!" portion for as long as possible.

Now whether this is intentional or not I don't know, but while it makes the pace a bit woozy (nothing new for Hooper), minimizing the time spent in the titular location is actually a good thing, because let's face it - the idea is ludicrous. Even if we ignore how implausible it is that this traveling carnival would have such an elaborate ride (with two floors!), how can they possibly be unable to escape a ride that by design is meant to quickly get the marks back out into the carnival grounds to spend more money? Especially when it's a track ride - all the characters had to do was follow the path around until it came to the exit (think about it - a door can't exactly fully close on a track), so if they got trapped in there at the end of the movie's first act there would be too much time for the audience to notice that the concept doesn't quite work.*

This was presumably not lost on Dean Koontz when he was hired to write the novelization, as he actually manages to *reduce* the time they spend trapped in there, with the sequence lasting only 36 pages of his 330-page book. So what happens in the other 300 pages, you might ask? A hell of a lot that I am willing to bet neither Hooper or Block ever considered. Ironically, the book comes closer to slasher movie territory than the film does, as we are treated to three additional deaths (two carnival attendees and a safety inspector) to tide us over until the big showdown between our hero teens and Gunther (and his carnival barker father, Conrad), effectively doubling the body count. Gunther also speaks a bit more here, and it makes him more sinister as we see he kind of knows what he's doing, as opposed to the film version that comes off more as a fucked up Lenny from Of Mice and Men than a traditional boogeyman.

But even those bonus kills wouldn't fill up a whole book, so Koontz (who published the book under his old pseudonym, Owen West) also invents a backstory not only for Amy, the film's protagonist (played by Elizabeth Berridge) but also her strict mother, Ellen. Without knowing the script Koontz was working from I can't be 100% sure, but it seems like he took inspiration from throwaway details in the film - such as Ellen's tendency to have a drink in her hand - to create fully fleshed out arcs and histories, to the extent that Ellen (and Conrad himself) are the focus of the book just as much as Amy is. According to the book, Ellen and Conrad were married when she was only about twenty, and they had a child that came out as more of a creature than a human. She murdered that infant (who was, at only a few months old, already able to sit up and fight back - it takes her a lot of effort to finally kill it) and was beaten to a pulp by Conrad, who planned to kill her as punishment for murdering the son he loved. But ultimately he opts for a more long-term revenge, letting her go in the hopes that she would remarry and have other kids (normal ones) that he could torture and murder in kind when the carnival came to their town.

Koontz thankfully has one of Conrad's fellow carnies point out the incredibly tiny odds that this will actually work, but anyone who has seen the movie knows he'll at least get his chance, as Ellen goes on to have Amy with another husband and does indeed end up at the carnival where Conrad and his new son (another "beast") are in charge of the titular funhouse. Conrad is assisted by Madame Zena (the Sylvia Miles character from the film) who uses her phony fortune teller shtick to find out more about the youngsters that remind him enough of Ellen to warrant a closer inspection (she asks them their background, how old their mother is, etc. and reports back to Conrad if the histories match up). In the movie, of course, there is zero indication that he set his sights on these specific kids - he's just a typically creepy carny and they are doing dumb kid shit when their paths cross, plain and simple. In fact, the book doesn't even have them planning to stay in the funhouse at all (again, this might be Koontz trying to minimize how far-fetched it is), just riding it like they did any other ride when it breaks down and instantly being menaced by the father and son team. They do not witness a murder or steal Conrad's money in the book - they just fall into his preconceived trap.

Even this stuff doesn't quite match up to the film, though as mentioned it's possible Koontz had a different script to work from. He definitely had something close to what they used, however - Richie's death is pretty much exactly the same (right down to Buzz attacking his corpse with an axe), and Gunther's comeuppance is fairly similar as well. Liz's demise is also similar; there's no industrial fan but she again dies after a failed attempt to pretend to be open to Gunther's pathetic sexual advances. But other details in this section are different, some due to the fact that the story is different, such as Madame Zena's death. In the movie, she is killed by Gunther after he pays her for sex (a rendezvous that is cut short when she rubs his junk a bit and he climaxes before they even really get started), angry that she won't give him the money back. Well, in the book it turns out Zena is Gunther's mother, and while that wouldn't exactly rule out their arrangement as depicted in the film, it would make the film even ickier than it already is, and likely was never the intention of its creators. So instead she is killed here by Conrad, after realizing Amy is indeed the target of the man's revenge and tries to stop him from going any further.

Another big change involves Amy's brother, Joey. As in the movie he is a monster kid who likes playing practical jokes, but everything else about him is fairly different here. He doesn't use his own money to get into the carnival - he is gifted a pair of passes by Conrad, who suspects him of being Ellen's son, and his main reason for wanting to go to the carnival in the first place is that he plans to run away from home to join it, living the dream life of a carny. And rather than ride the funhouse normally and go on a separate adventure with a number of middle aged weirdo dudes (especially the carny that contacts his parents to come get him - he's WAY too into cleaning Joey up), he is kidnapped by Conrad and trapped in the funhouse with the others, a plot point I wish existed in the film as Hooper provides almost no payoff to his scenes. We also see that he and his sister are actually quite close and that his pranks are part of a little routine that they have, as opposed to a genuine annoyance to Amy as depicted in the film.

People who like to say Koontz is a second rate Stephen King will get plenty of backup for their argument here, as Ellen's devout Catholicism is the result of her tryst with an older man who impregnated her, not unlike Carrie's Margaret White. Some of the taunts Ellen bellows at her daughter are almost verbatim the same as the ones hurled at poor Carrie, telling her that men want nothing than to stick their filthy cocks in her and that they should pray together in order to keep her from being committed to hell. Of course, since we're in Ellen's head more than we ever were for Margaret this allows for a bit of sympathy to her plight, as she herself was abused with religion by her own mother and has been convinced that since her first child was a monster, these two others (Joey being a mistake, we learn) might look normal but will probably turn out evil as well, just to punish her. She also gets drunk and stumbles into Joey's room to confess her crimes, but of course the little kid has no idea what she's talking about and feels sorry for her. All of this seemingly spurned from the film version of the character having a drink and forbidding her daughter to go to the carnival (a conversation that actually never occurs in the book).

Now, a novelization author fleshing out things in the film is certainly nothing new - the best ones are the ones that offer up some additional details, even if they weren't intended by the filmmakers. As long as they don't contradict the film, it's just a fun thing to think about while watching if you want, but that's not really possible here. While he ultimately more or less novelizes the movie, it takes up less than a quarter of his book, and his revelations can't possibly connect to the feature, i.e. the aforementioned Zena stuff and a few other little details (the Buzz and Amy in the movie seem to have known each other for a while before going out on a date; in the book it's more or less a blind date set up by Liz). I mean, I guess if you want to pretend Gunther is getting a hand job from his own mother that's your prerogative, but for me and hopefully most of you, you'll see that even though it's a novelization, the relation between the film and the book is more like a film that was based on a book and revised heavily by screenwriters. Some people have even believed that Hooper's film was indeed based on this Koontz novel (a myth not helped by the fact that a delay in the film's production caused the book to be released much earlier), because it goes above and beyond the usual "oh the novelization has some stuff that's not in the movie" thing. It's more like Hooper and co. found a book about parental guilt and religious oppression and decided to option it because they liked the "kids at a carnival" stuff from its final two chapters, figuring it could be stretched out to a feature.

At any rate, it's worth checking out if you're a fan of the film, and if you *disliked* the film you might want to give it a look too, if only for the stronger narrative (and, admittedly, better pace), plus most editions have Koontz's explanation for why the two differ so much. I haven't read enough Koontz to judge his abilities, and wouldn't do so on a paycheck-grabber from early in his career anyway, but it held my attention both as a fan of the film and as someone who enjoyed this fan fiction-y prequel take on it. I wish it started a trend of novelizations that treated the film as the third act (it's the inverse of Roger Corman using Poe stories as the third act of his film adaptations!), but as far as I know no one else has ever gone this far off source when hired to adapt a screenplay. As a novelization fan, I must champion the attempt, even if he ultimately got a bit too creative and ended up making it impossible for the novel to match up to the film. But it beats translating the script word for word, that's for sure.

*A movie that ripped this one off a bit, called Dark Ride, at least had the good sense to set theirs in a permanent amusement park structure instead of a traveling carnival. It is otherwise an awful movie, however.