CHASING THE DRAGON Review: Bromance Of The Two Kingdoms

Chasing the Dragon unites Donnie Yen and Andy Lau, two titans of Hong Kong cinema, in a decades-spanning crime saga involving a notorious real-life pair—gangster “Crippled” Ho and police sergeant Lee Rock. Curiously, both men’s stories were adapted for the screen in 1991: Ray Lui portrayed Ho in Poon Man-Kit’s To Be Number One, while Andy Lau headlined Lawrence Ah Mon’s Lee Rock and its sequel. At face value, Chasing the Dragon seems like a throwback to 1990s-era Hong Kong cinema, but upon closer inspection, the resemblance is merely a façade. As with the film’s protagonists, there’s an emptiness behind the mask.

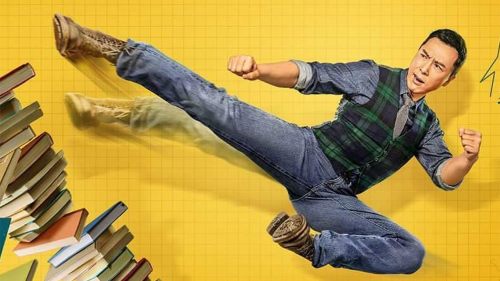

Co-directed by Wong Jing and Jason Kwan, Chasing the Dragon stars Donnie Yen as Ng Sek-Ho, an immigrant who comes to Hong Kong in 1963. While protecting his friends, Ho runs afoul of the Royal Hong Kong Police Force but makes an unlikely friend in Lee Rock (Andy Lau), a policeman who views Ho as a potential ally in his rise to power. Through the miracle of cinematic montages, the two men join forces to climb the ladders of their respective organizations: Ho in the criminal underworld, Rock in the deeply corrupt police force. Eventually, the two friends are placed on a fateful collision course, as their respective kingdoms are put in jeopardy. Can their bromance possibly survive?

Like Jackie Chan before him, Donnie Yen seems interested in developing his dramatic chops, perhaps looking ahead to a future when he can no longer pull off those amazing kicks. However, this is no DeNiro or Pacino moment for Yen. Wide-eyed, preening, and melodramatic at times, the actor walks a fine line of being ridiculous, although likably so. In his defense, it’s hard not to look silly in a goofy wig, a cheesy moustache, and flamboyant period costuming.

At fifty-six, Andy Lau reprises a role he last played when he was thirty—and doesn’t miss a beat. Thanks to his matinee idol looks, Lau has played heroes for most of his career, but he’s much better portraying morally ambiguous characters. Letting the mask of politeness slip every so often, Lau reveals a cold, calculating schemer underneath. At the same time, his movie star persona can effortlessly convince audiences that Rock’s aims are noble, even when he’s amassing millions of dollars through illegal bribes.

Seeing these two actors play off each other is a definite treat, but Chasing the Dragon still leaves much to be desired. The film is beautifully shot, but its glossy veneer masks ample deficiencies: a saggy plot, undeveloped characters, and a CliffsNotes version of gangland history. This haphazard approach is most egregious in its portrayal of women. None of the actresses are given a single meaningful piece of dialogue, let alone a full conversation with another human being. Their roles involve little more than smiling, crying, or dying, with at least one achieving the latter two in a single scene. While Hong Kong cinema possesses a long history of so-called “flower vase” parts—that is, roles in which actresses do little more than show up and look pretty for the camera—that doesn’t make it right.

“Guy Movie” or not, Chasing the Dragon is an uncritical celebration of its deeply flawed male leads. After all, Lee Rock was a crook who amassed $64 million through kickbacks, and “Crippled” Ho was an infamous heroin kingpin (in fact, the original English title of the movie was “King of the Drug Dealers”). To a certain degree, all gangster films glamorize the criminals they depict, but there’s something disingenuous about Chasing the Dragon’s thesis. The real villains, according to the film, are the British, who allowed this rampant corruption to exist, not our plucky “heroes,” who took full advantage of the situation to line their own pockets. Thus, a biting critique of British imperialism is rendered mostly toothless due to the film’s cartoonish handling of real-life events.

And yet, despite my reservations about Chasing the Dragon, there is something to recommend beyond the lead actors, the cinematography, and the retro soundtrack: a stunning action sequence set in Kowloon Walled City. In this impressive scene, Rock walks into a trap, and Ho must save him from certain death, as gangsters pursue them through numerous labyrinthine alleyways. While “Chasing the Dragon” is Cantonese slang for heroin use, it has come to mean the vain pursuit of recreating one’s first high, and is, in a weird way, an apt metaphor for my viewing experience. The aforementioned chase scene is tense, exciting, and ultimately euphoric— perhaps the only time that the movie truly resembles the very best Hong Kong films of the 1990s, a cinematic era where anything was possible and any moment could be genuinely exhilarating.