BMD Picks: Our Favorite Friday The 13th Viewing

"His name was Jason, and today was his birthday."

Obviously, Friday the 13th was a superstitious person's calender nightmare long before Sean Cunningham and Victor Miller made Friday the 13th (their legendary exploitation work was conceived title-first, after all). Still, the date has become synonymous with their movie, and since labeled a horror freak's "holiday". Just like on Halloween, we're able to watch our favorite scare pictures free of folks side-eyeing us like weirdos. To celebrate, most of the BMD clan got together to toss out some of their most beloved fright titles. So, maybe choose a few from this list before you settle in for a good scare tonight...

*****

Friday the 13th: The Final Chapter [1984] (d. Joe Zito, w. Barney Cohen)

Let's say you've somehow lived this life of yours without ever experiencing the pure and simple joys of a Friday the 13th film, and want to use its namesake "holiday" as a reason to start. If so - or if you're just having trouble deciding which one to rewatch - my suggestion is 1984's entry, subtitled The Final Chapter. In a way, even the title perfectly encapsulates the relentless appeal of this series; not only was it NOT the "final" entry by any measure (there were eight more), but the next installment came out quicker than any other entry before or since, as if Paramount didn't even want to tease out the "death" of the series for a full year before reviving it.

However if they called it "The BEST Chapter", it would have been more accurate. For my money - and believe me I've spent a lot of it on this series over the years - there is no better installment, and it will be just as entertaining to a newcomer as it is to a series veteran. Director Joseph Zito and screenwriter Barney Cohen distilled the formula to its base essentials, while giving us some of the series' most likable and memorable victims (Crispin Glover's hapless Jimmy is probably the most normal character he ever played) and some genuine suspense, which most of the later entries lacked once Jason was just a zombie and the people he hunted might as well have been, too. It also introduced Tommy Jarvis, the closest the series ever had to having its own Van Helsing or Dr. Loomis, and besides young Jason, he was also the first actual child in the series (played by 12-year-old Corey Feldman); interesting for a franchise that ostensibly revolves around a kids' summer camp.

It also gave us a gold standard Jason; in fact, Ted White's incarnation was the only one that scared me enough to give me a nightmare when I was a kid, and his Tom Savini-designed makeup is so gnarly you almost wish he didn't have his hockey mask on the entire time. Oh yeah, this is the first one where he has the hockey mask the entire time, so it's the first one in the series that a newcomer might not be disappointed with after hearing about the legendary hockey masked killer Jason Voorhees from their horror-loving pals. And that's what makes it the ideal choice for today: it's got the best chance of any entry to convert someone to a fan, and if you're already a fan it will give you everything you'd want. - Brian Collins

Black Christmas [1974] (d. Bob Clark, w. Roy Moore)

It's kind of disappointing that Bob Clark's A Christmas Story became the holiday staple instead of Black Christmas. I mean, imagine cozying up by the fire on Christmas day with a cup of hot cocoa and a twenty-four hour marathon of a trailblazing slasher! Released in 1974 - prior to heavy hitters like Halloween and Friday the 13th - this yuletide horror laid the groundwork for the slasher sub-genre fortified by John Carpenter. Black Christmas became the model filmmakers used to create the most common rules and tropes in horror. However, it's the areas where this film deviates from the "rules" that make it standout.

Decking the halls with eerie atmosphere and the screams of sorority girls, Clark and screenwriter Roy Moore launched the film that made us afraid of attics and ringing telephones. When a group of sorority sisters receive an obscene phone call from a man they call "The Moaner," their holiday cheer turns to fear in an instant. The phone calls are unnerving because of the creepy sound of overlapping voices and inhuman noises on the other end of the line. Anticipating the sound is enough to make your skin crawl every time the phone rings. When the caller's heavy breathing and perversions turn to death threats, the girls start disappearing one-by-one. Unlike the climactic ending of 1979's When a Stranger Calls, we're aware that "the calls are coming from inside the house" from the very beginning. The ingenious tactic of revealing right away that a homicidal maniac is hiding in the attic increases the tension each time someone heads upstairs.

The outstanding female cast - including a scene-stealing Margot Kidder and the ultimate Juliet, Olivia Hussey - are independent and ambitious women, free from the subsequent trope of playing victims in waiting. Also absent from the film is the sex equals death rule, given that a virgin dies and the Final Girl (Hussey) plans to have an abortion. Even with all the dark themes, there's a good balance between comedy, drama, and suspense owed primarily to Clark's direction of his talented cast. His use of POV shots to mask the killer's identity suggest that it could be anyone, leaving the viewer to come to their own conclusion. While the killer's schizophrenic ramblings keep you on edge, Clark trades gore and violence for dread and suspense, making you hyper-aware of every creak in the house. The last act unfolds in a terrifying confrontation between killer and Final Girl, but you'll have to watch to find out which rules do and don't apply.

While this slasher is a staple every Christmas and Halloween, it deserves to be celebrated year round. So, before you cozy up by the fire with your hot cocoa tonight, be sure to check the attic. And turn off your phone. - Emily Sears

Rosemary's Baby [1968] (d. & w. Roman Polanski)

With recent releases like Annihilation and A Quiet Place (and probably the king of them all, Get Out), there's been a push to label “actually good” horror films with a nomenclature that elevates it as something better than just horror. If an engine for stupidity as big as Twitter existed back in 1968, people would apply this to Rosemary’s Baby as well.

I tend to prefer my horror tied to action or comedy, but when it comes to a straight-up dose of the genre, Rosemary’s Baby will always be my number one. Mia Farrow’s performance, the way that amazing apartment becomes a prison, the allowance for slight humor out of nowhere (look, the people tip-toeing around behind Rosemary are terrifying but also slightly funny), and of course that ending. Just like Get Out, Rosemary’s Baby has plenty to offer in terms of social significance. While there is an undeniable element of separating art from the artist with this one, I just can’t let go of the fact that it’s a masterpiece. - Evan Saathoff

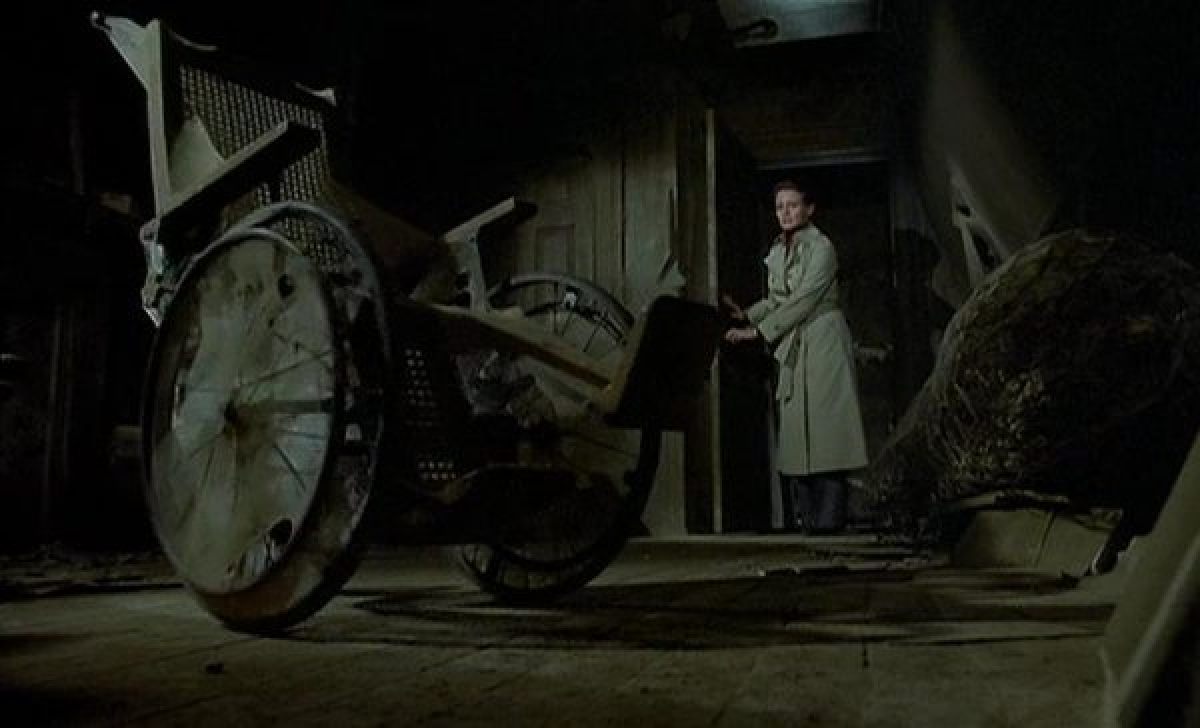

Session 9 [2001] (d. Brad Anderson, w. Stephen Gevedon & Brad Anderson)

A decade and a half ago, my then-girlfriend and I walked into a Blockbuster Video to see what we could see. The "New Release" wall wasn't doing much for us, but then - just as we were ready to pack it in and go home - one of us noticed the cover box for Session 9. It featured a dark hallway, a creepy chair, and what appeared to be a dude wearing a hazmat suit. We knew nothing else about the film, but the cover box was enough to separate us from our $3.99.

Roughly two hours later, my life had been irrevocably split into two chapters: "Before Session 9" and "After Session 9". I have been singing the praises of Brad Anderson's masterpiece ever since.

Filmed on location in an actual abandoned insane asylum - a description that honestly doesn't even begin to do Danvers State Mental Hospital justice - and featuring both a murderer's row of character actors and a razor-sharp script by Anderson and Stephen Gevedon, Session 9 may be the horror movie I've watched more than any other. To my eyes, it is the Queen Mother of "spooky insane asylum" pictures; an unsettling and oddly emotional horror-thriller whose criminally-underrated status I will never stop bitching about.

I love Session 9. If you can't fuck with it, I can't fuck with you. - Scott Wampler

The Changeling [1980] (d. Peter Medak, w. William Gray & Diana Maddox)

If you've ever worked in a video store, you more than likely had to recommend movies to a mainstream customer (Jacob's Note: can confirm this is a chore). Maybe you had your own section, or maybe you had lists behind the counter of your favorites. I knew every Halloween or Friday the 13th, there would be a ton of requests for horror films, and my go-to for the average "not gory" customer was Peter Medak's The Changeling. It's easily my favorite haunted house film of all time, grounded by a performance from the great George C. Scott, who plays a musician still devastated from the death of his family in a tragic car accident. Moving to a large house in Seattle to teach a music course at the local university, he quickly finds he's not alone in the house. His ghostly roommate starts by banging pipes, but his violent and malicious nature becomes apparent over the film. While this ghost may want the living to right the wrongs committed against them, you begin to wonder if that alone will quench his thirst for vengeance.

The Changeling is just scary. It's got my favorite cinematic seance scene, and masterfully uses the most ordinary and benign objects to instill terror in viewers. It's also a movie that most audiences can enjoy as its scares are psychological rather than shocking, or visceral and graphic. It's a great ride and it's an easy recommend. If you haven't had a chance to see it yet, its actually recently been remastered and enjoying a limited theatrical run through AGFA ,and will be out on Blu-ray later this year through Severin. - James Emanuel Shapiro

It Follows [2014] (d. & w. David Robert Mitchell)

The concept of a monster that acts as a sort of sexually-transmitted stalker is an eerie conceit that would make for a wholly original film regardless of thematic depths. However, It Follows strikes on brilliance by adding one more detail to the equation: the monster can look like anyone. Not only is this used to create some truly disturbing imagery as the monster horrifies with deranged and leaking visages, but it acts as a sort of camouflage so that its victims are never quite sure whether the monster is among the crowds necessary to navigate in daily life. Cinematographer Mike Gioulakis turns the audience's paranoia against itself, forcing one to scan over every person in a shot to make an educated guess as to whether that person is actually a slowly shambling monster in disguise. What could have been a very basic story about the dangers of STIs is instead transformed into a vicious take on how no one is trustworthy. Monsters hide among us every day, and particularly for young women that danger is sexual in nature, whether it's forcefully violent or a violation of trust from a consensual partner. It Follows is about those violations and how they shape our view of the world around us, and in the end you may never find someone trustworthy enough to finally be completely safe. - Leigh Monson

Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me [1992] (d. David Lynch, w. Robert Engels & David Lynch)

Last year's Twin Peaks: The Return inspired no small amount of debate as to whether or not the relaunch of David Lynch and Mark Frost's iconic series was, in fact, television or a movie. I suspect calling Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me a "horror movie" will incite similar debate amongst some viewers, but anyone suggesting that it's not terrifying is very wrong.

Indeed, Fire Walk With Me is one of the scariest movies I've ever seen. From Laura Palmer's brain-melting realization concerning the truth about BOB, to the fever-dream cameo turned in by David Bowie, to the goings-on above that convenience store, to the truly unsettling moment where a kid in a white mask capers around the Double R Diner's parking lot, this thing is overflowing with nightmarish imagery. It all crescendoes in an apocalyptic, soul-shattering moment of violence, one I've never even come close to getting over. - Scott Wampler

Sleepaway Camp [1983] (d. & w. Robert Hiltzik)

The summer camp slasher is an American repurposing of Italian giallo tropes (think: Bava's Bay of Blood) with a texture all its own. You can feel the rough grain of the cabins' wood beneath your palms. An aroma of wet pine drifts just under your nostrils. Kids chant and play with one another during the day, while the nights are black voids, punctuated by the crackling of an open fire. Friday the 13th started this trend during the early '80s - a movie that was conceived via phone call with only a title and a setting in mind, before adding in the now requisite slasher movie sex and death. Thanks to the millions of dollars Friday made at the box office - the independently financed junker out-grossing even distributor Paramount's '80 Best Picture winner, Ordinary People - a wave of knock offs of course followed in its wake.

Robert Hiltzik's Sleepaway Camp may not be the best of these riffs, but it's certainly the most fascinating, taking the sexuality of Friday the 13th and positioning it front and center, resulting in an abrasive interpretation of teenage hyper-suppressed carnal urges. From the moment the kids are bussed in to idyllic Camp Arawak, we're confronted with them as yearning mounds of flesh, the counselors who guide them clad in the shortest shawts and sporting Long Island accents. All the while, an obese, sweaty cook licks his lips and comments on how appealing they are to his diseased libido. Writer/director Robert Hiltzik knows what game he's playing, and we're skeeved out throughout the rest of Sleepaway Camp' scant, bloody 84 minutes. Naturally, sex leads to death, as many of the kids and their temporary keepers are mangled and mauled in gruesome fashion.

Sleepaway Camp's elephant in the room has always been the last second reveal of Felissa Rose's gender-bending brutality artist, Angela. The villainess' sex crisis arose thanks to Hiltzik's exploitation-minded desire to spin the slasher formula on its head, the reveal that "she" is actually a "he"; a natural byproduct of attempting to create a crass cinematic encapsulation of youthful lust. Outside of horrific murder, much of the movie's running time is devoted to watching kids try to touch each other, as Hiltzik is practically poking every pervert seated in the auditorium. Having the central character turn out to be a possible trans* individual - it's questionable as to whether or not Peter/Angela actually self-identifies as a woman any more than simply adhering to forced transvestitism, as so little of the movie is actually told from their perspective - further emphasizes the picture's phantasmagorical devotion to ever-evolving youths in heat. Angela becomes a quite literal "late-bloomer"; summer camp standing in for the usual spring metaphor. All of it is nonsense, of course; but that's why you sign up to watch low-budget DIY mayhem in the first place. Every once in a while, you find a filmmaker packaging personal messaging inside of their lowbrow schlock; a mush-mouthed attempt at expressing some transgressive notion via a motion picture that also features a hot curling iron getting violently shoved up a victim's vagina. - Jacob Knight