The Savage Stack - ACROSS 110TH STREET (1972)

There’s always going to be – for lack of a better term – a stack of films we’ve been meaning to get to. Whether it’s a pile of DVDs and Blu-rays haphazardly amassed atop our television stands, or a seemingly endless digital queue on our respective streaming accounts, there’s simply more movies than time to watch them. This column is here to make that problem worse. Ostensibly an extension of Everybody’s Into Weirdness (may that series rest in peace), The Savage Stack is a compilation of the odd and magnificent motion pictures you probably should be watching instead of popping in The Avengers for the 2,000th time. Not that there’s anything wrong with filmic “comfort food” (God knows we all have titles we frequently return to when we crave that warm and fuzzy feeling), but if you love movies, you should never stop searching for the next title that’s going to make your “To Watch” list that much more insurmountable. Some will be favorites, others oddities, with esoteric eccentricities thrown in for good measure. All in all, a mountain of movies to conquer.

The seventy-second entry into this unbroken backlog is the ragingly pissed Blax heist procedural, Across 110th Street...

For most modern film fans, "Across 110th Street" is a cheeky reference in Quentin Tarantino's Jackie Brown (’97) that they only half-understand. While it's not difficult to decipher that the song our favorite badass flight attendant is singing along to while she drives away in Odell Robbie's stolen vehicle is probably the theme to one of QT's favorite Blaxploitation pictures, once you sit down with Barry Shear's (Wild In the Streets ['68]) blisteringly angry work, it instantly becomes clear that the source couldn't be more different from the motion picture citing it. Across 110th Street ('72) isn't just one of the most infuriated entries into the Blaxplo canon. It may be one of the most incensed pop indictments of American society ever committed to film, positing that we're all in a constant state of class warfare, and that any attempt to escape our current station may in fact be an act of self-destruction.

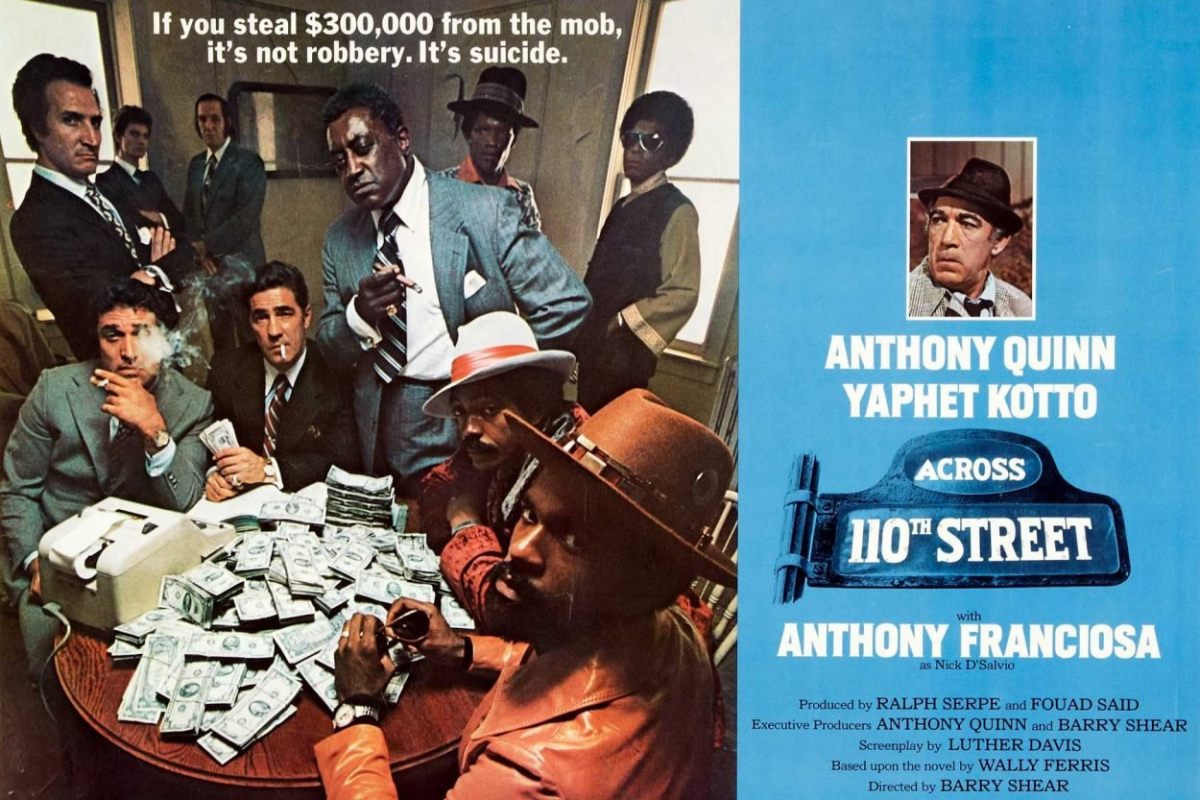

Even the original one sheet's tagline warns us we're in for a fatalistic bout of action filmmaking: "if you steal $300,000 from the mob, it's not robbery. It's suicide." Essentially, Across 110th Street’s entire plot is contained in those two sentences. A trio of desperate hoods – Jim Harris (Paul Benjamin), Joe Logart (Ed Bernard), and Henry J. Jackson (Antonio Fargas) – rips off a mafia drop for a suitcase full of cash. When one of the bodyguards at the meet develops an itchy trigger finger, Harris unloads his machine gun and kills everyone in the room but his wing man, leaving a stack of white and black bodies in a Harlem apartment. On their way out, the crew takes down two more cops. Now, they're Public Enemy No. 1 for both the Mafia and the blue boys, and we can feel the noose tightening around their necks with every minute that ticks away on the movie's hasty 100-minute runtime.

However, these men have been feeling the crushing weight of society's pressure long before screenwriter Luther Davis (Kismet ['55]) – adapting Wally Ferris’ novel of the same name – checks in with them. After the robbers escape, Joe's right back to work at the dry cleaners, while Jim's arguing with his better half, Norma (Norma Donaldson), who's scared for their lives. "I'm not gonna go back to cleaning up after some white man," he says, knowing he's barely got a shot of making ends meet as a custodian (or any other menial labor he can attain), and warns that, without this money, there may come a day when he looks the other way while Norma turns tricks to provide her share. Out of the three, Henry's got the right mind to live it up; hitting the whorehouse and tossing bills around like it’s nothing. He's never had money like this before, so the man's gonna spend it. Unfortunately, Henry’s frivolity attracts the attention of the mob's mad dog, Nick D'Salvio (Anthony Franciosa), who's looking to literally crucify the thieves that stole from his family.

This class warfare isn't just limited to the criminals, as the detectives assigned to the case are dealing with their own social battles. Captain Mattelli (Anthony Quinn) is a 55-year old cop who knows that the new blood beneath him are looking to push this racist brute into retirement. The younger, progressive generation is represented by Lt. Pope (Yaphet Kotto), who doesn't agree with Mattelli's violent bullying tactics when it comes to questioning (mostly black) suspects. The Captain wants to take the case for himself, but his superiors inform him that the Powers That Be need Pope in charge. "Is it because he's black?" Mattelli barks, only to get "it's just politics" in response. But that's all anything is anymore: politics instead of police work. At least, that’s the way the Old World Italian understands these demands. Mattelli is about to be steamrolled by evolution, and this throwback is ready to lie down and die.

Racial tension is almost always the fuel that powers a Blaxplo picture, but Across 110th Street instead tosses anxiety into a powder keg and then lights the fuse, allowing each individual’s bigotry to explode via ugly violence – both emotional and tactile – in almost every scene. Just as Mattelli knows being pushed out of his position is a near inevitability, the Mafia worry the blacks in Harlem are done sharing their turf with La Cosa Nostra. These people have figured out how to empower themselves, and are done taking a percentage when they can have the whole fucking pie. At the center of nearly every fictional scenario is fear – fear of corruption, of poverty, of death – that throws the entirety of New York City into absolute chaos, and divides these races, to the point that they barely see each other as human beings. "When are you gonna start looking at me like a cop?" Pope finally screams at his white counterpart, verbalizing the movie's themes in one frighteningly intense moment of near-Brechtian performance. It’s absolutely brilliant.

Yet Shear never forgets that Blaxplo had become one of the best arenas for action filmmaking during the early '70s, and peppers set pieces into the whole of Across 110th Street that are visceral and daring. The climactic rooftop shootout between Harris, the cops, and the mob is a miracle of live-shooting geography, as one of the last-standing bandits scrambles across the tops of tenement buildings, mowing down anyone who stands in his way. Meanwhile, the torture and murder D'Salvio enacts on his quest to secure his employers' cash sickens the henchmen of his already shaky black business partner, Doc Johnson (Richard Ward). The Italian bag man is practically lynching these African Americans, and all it'd take is one bullet to end his reign of terror. Yet the rickety truce between these underworld factions must remain, lest the ensuing race war burn Harlem to the ground.

These pulpy black and white businessmen stand in for the overall disharmony that existed in NYC during the '70s. Across 110th Street may be a work of pop fiction – working in a mode of exploitation that was experiencing quite the boom during the period – but it’s still attempting to relay a rather awful truth the only way it knows how. Shear's film bursts at the seams with an almost singular level of resentment for the way those of different races viewed each other, while capturing the bombed out wasteland that was Harlem during the early '70s. The ghetto had become a battleground, where even those who were assigned to keep it safe were constantly at each others' throats, totally terrified of any sort of change. In short, Across 110th Street is a document of discontent that ends on a note of utter hopelessness, as if knowing – nearly fifty years from now – we'd still be tearing each other apart because we not so secretly despise tribal differences.

Across 110th Street is available now on Blu-ray, courtesy of Kino Lorber.