The Timelessness Of GREASE

It’s a strange experience, attempting to analyze the pop culture that fuses itself to your psyche and soul in some distant, half-remembered kind of way. These stories, films and shows may not be the best or most accomplished work out there, but they have an unspoken bond with your own relationship with time and memory, and uncovering their moving parts can feel like a sort of violation. I was raised on The Lion King, Jurassic Park, Toy Story. These are films that for me, like many others in my generation, can be hard to return to because of the raw nostalgia they serve in excessive quantities.

This is Grease, too, a musical whose cultural impact spans decades. It’s one of those films that bridges generational gaps, as many musicals do - what was a vital piece of youth culture for my parents’ generation became a symbol of childhood and of Saturday night family movies for mine (despite some really quite questionable content within). My mother describes going to Grease as a teenager out of a feverish desire to get more Travolta, post-Saturday Night Fever. I, meanwhile, am reminded of summer holidays as a kid, and sitting down in front of one of those old box television sets to watch a flickery copy of the film with the whole family. Both of these are now distant memories and yet, Grease remains - from live television recreations to folksy acoustic covers of ‘You’re The One That I Want’, something about Grease, perhaps more so than any other musical except The Wizard of Oz, permeates the public consciousness. It’s an institution, like The Simpsons, or Star Wars, the kind of work that teaches us how to operate within the pop cultural world. What it is that gives Grease this peculiar, magnetic power is less clear.

It would be easy, a week after Grease's fortieth anniversary, to reference the things people most often talk about when they talk about the film - the abundance of off-colour humour throughout that went soaring over the heads of astonished children, or the difficult politics of a film that simultaneously upholds and critiques restrictive fifties gender roles in the wake of the counter-culture movement that seized the world at the time of the film’s creation. There are the songs, whose infectious energy surely help to enable the timelessness of the film itself, or the superb performances from a cast of definitely-not-teenagers at the top of their respective games. An element I think goes underpraised and yet has a vitally important role in preserving the film as a generations-spanning classic is its direction. Filmmaker Randal Kleiser manages that most important aspect of adaptation from stage to screen - he remembers that they are two fundamentally different mediums. Too often, directors of such adaptations forget that the camera is as vital a player in a film as another actor alongside someone on-stage.

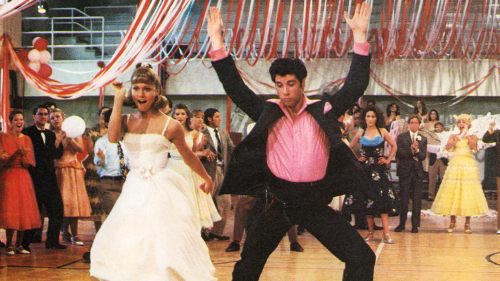

Kleiser and cinematographer Bill Butler integrate the camera into the choreography of the musical numbers - using light, colour and movement to keep the energy and joy of the performances up throughout. Consider the iconic ‘Born to Hand Jive’ sequence - the camera weaves, ducks, whips around to catch little moments throughout, like an overwhelmed teen at their first party trying to take in everything at once. Performers have been directed to dance across the path of a moving camera, so that we get the sense of action happening all around us without ever taking in the entirety of the thing, leaving us wanting more. The performers don’t control where the camera goes, it roves, doing what it pleases. The frame is filled with colour and detail, from the slash of Danny Zuko’s pink shirt to the buoyant blue of Cha Cha’s dress, but it’s never garish - by using real locations instead of sets there is a palpable sense of griminess, of overuse, in the bleachers and faded gymnasiums and dusty drive-ins the characters populate. The graduation fair at the end of the film definitely wouldn’t be up to code nowadays.

Returning to Grease, I’m always struck by the way the film is at once a rip-roaring good time, with enough flash and pizzazz to keep younger audiences from recognizing the far more adult undercurrents at play, and a surprisingly complex and detailed work. Not content to rest on the undeniable magic of ‘Hopelessly Devoted to You’ and ‘Greased Lightnin’’, the film invests whole-heartedly in developing its characters as worthy of these immense songs.

Like most of my favourite musicals, the songs serve as either stylistic interludes or to shine a light on the inner workings of the characters, stopping the narrative in its tracks in order to deepen our understanding of what’s going on with these people we are asked to invest with. Rizzo’s devastating performance of ‘There Are Worse Things (I Could Do)’ lands with the force of a ton of bricks because the film has spent the previous hour or so fleshing out both her and Kenickie with little flourishes that endear them to us (such as the fact that Rizzo outright refuses to join in with the choreography of ‘Summer Nights’). By investing so deeply, the probably not that significant activities of these definitely-not-teenagers feel practically life-or-death by the time the climactic car race rolls around. It’s the little grace notes that make these characters feel like your high school friends - the fact that Sandy is immediately made to be a cheerleader and is clearly terrible at it, the obscenely performative masculinity of the T-Birds even though Danny and Kenickie definitely want to make out, the way Doody pulls out a water gun to fight the Scorpions, the hilarious interplay between the Principal and her hapless assistant. Rarely has a group of characters been so instantly iconic and recognizable forty years on.

There’s not one reason why Grease remains a singular musical, one that holds up and one that will doubtless be shown to generations to come, as other big musicals of eras that have come and gone fade from memory. It’s one of those cinematic perfect storms, a film built off nostalgia even before Grease became a virtual stand-in for the idea of nostalgia itself. It is both a time capsule and one of those key works that help us to understand the way pop culture evolves around us.

Danny and Sandy definitely broke up like two weeks after the end of the film though.