CATCH-22 Review: The Ever-Tightening Spiral Of Irony

Catch-22 is a notoriously difficult novel to adapt, mainly due to its odd structure that hops between characters anachronistically in order to offer multiple perspectives on the same events and allow the gravity of war to sink in through repetition and gradually enhancing grisly detail. This sort of storytelling is not particularly well-suited to a visual medium, so the trouble will always be in capturing the cynical dark humor of the novel while retaining the impact that this repetition delivered. This Hulu miniseries adaptation, written by Luke Davies and David Michôd, manages to retain the novel's cyclical nature without resorting to repetition of events, and the resulting narrative feels at once of a piece with the novel and its own unique spin.

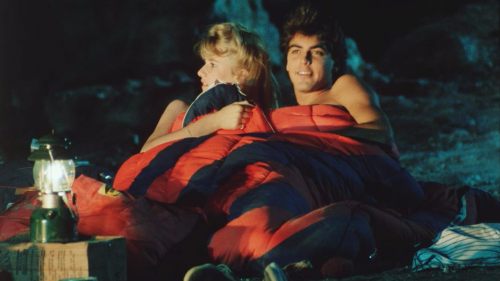

The first episode’s opening moments introduce us to a plethora of American soldiers circa World War II undergoing the repetitive and ultimately useless exercise of parade drills under the tyrannical tutelage of Lieutenant Scheisskopf (George Clooney, also acting as executive producer and director of two episodes). As names flash by across the large cast of disposable heroes, it’s easy to believe that this ensemble will become unwieldy and hard to keep track of, but thankfully as the show settles in on its main point-of-view character, John “Yo-Yo” Yossarian (Christopher Abbott, delivering a hell of a performance), the key players become clear and the soldiers are allowed to blend into the background until their particular vignette is up to bat. Yossarian frames the narrative by continually attempting to get out of service as a flight bomber through schemes and attempts to circumvent the ever-escalating number of missions he is contractually obligated to fly, the irony being that there is no escape from his service no matter how hard he tries. Nowhere is this better encapsulated by the bureaucratic rule Catch-22, which, as Doc Daneeka (Grant Heslov) explains to Yossarian, prevents him from asking to leave combat due to mental instability because concern for one’s safety is the hallmark of a rational mind.

Catch-22’s humor is couched in fast-talking circular logic and farcical contradictions delivered with pacing somewhere between Abbott and Costello and Gilmore Girls. It’s purposely absurd and primarily serves to highlight the bizarre circumstances Yossarian becomes witness to. Milo Minderbender (Daniel David Stewart) enters the tour of service at the same rank as Yossarian, but convinces a materialistic major (Hugh Laurie) to allow him to take over the kitchens through a collaborative trade enterprise with enemy Germans, showing how the only winners in war are capitalist opportunists. The comically named Major Major (Lewis Pullman) is promoted to Major on the whim of a Colonel (Kyle Chandler) who can’t admit to his own mistake in assuming the man’s rank and would rather reward incompetence than admit to his own. Nately (Austin Stowell) falls in love with a prostitute and is intent on marrying her after the war, even though he must still continually pay for the time he spends with her and doesn’t seem to understand that it’s in a sex worker’s job description to be attractive to the client. Each of the series’ six episodes starts with misadventures such as these, but almost like clockwork the narratives take a sinister and tragic turn during the final act of any given episode, and though the light tone resumes upon the next episode’s resumption, the overall mood gets progressively darker.

This formulaic adherence at first feels like a fault in a show that was brought to episode order and needed to find a way to flesh out an arc for each individual episode, but when taken as a whole the structure feels intentional and necessary. The dark comic brilliance of both the novel and this adaptation is that you find comedy in the horror so that your mind can more easily process that horror. People dying in stupid, random, and preventable ways, due more often to the mechanical and thoughtless machinations of the American war machine than enemy fire, is a sickening joke at humanity’s expense, evidence of a world where God does not exist or does not care enough about us to prevent us from picking each other off, regardless of righteousness of cause. As that spiral of anxiety winds tighter, Catch-22 embraces the paradox by simultaneously leaning into the farce as much as it does the atrocity, and that tightwalk rope of tone is navigated expertly. The finale deviates from the source material somewhat in keeping with this theme, but it’s remarkably fitting given how much dramatic weight rides on such a dark and cynical story.

The only thing that diminishes the potency of that cynicism is the show’s over-reliance on montage set to period-appropriate radio singles. I don’t know if using these tracks was a cost-saving measure as opposed to commissioning more original score, but they set the historical stage over sequences that serve only to communicate the passage of time, so much so that the technique becomes overused and distracting.

This is, however, a minor quibble in a series that is mostly quite enjoyable. It’s brilliantly performed by the entire sprawling cast, and the writing is tight enough that this sprawl never feels unmanageable or confusing. It’s a bloody, horrific tale that settles on a nihilistic moral that the only way to survive is to find the humor in the despicable and bleak. It might not feel all that great to laugh in the face of the abyss, but it sure beats the hell out of crying, which might just be the greatest contradiction of all.

Catch-22 premieres May 17 on Hulu.