The DOJ, Exhibition, And That Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day

You’ve heard by now the Department of Justice’s Makan Delrahim, the citizen who heads up the DOJ’s anti-trust division and the person at the top of Trump’s vendetta to prevent AT&T’s purchase of Time Warner due to CNN’s coverage of his presidency, has moved to terminate the Paramount Consent Decrees. Last August, I wrote about the announcement and about the potential of studios owning theaters. Since then, it has become apparent that the lobbyists working this case were more interested in restoring block booking and circuit dealing than they were in paving the way for Disney to buy AMC or Regal. That may still happen, but I think it’s an extreme longshot for the simple reason that if block booking and circuit dealing come back into movie distribution, such purchases wouldn't be necessary as they’ll have all the leverage they need to dictate what you see and where.

Let’s define these terms first. Block booking is the process of selling several films to a theater chain as a slate. This allowed studios to bundle lower demand content with higher demand films. In the past, the bundle could include a year’s worth of films at terms that would guarantee profit. The best way of looking at this now would be if a theater wanted to play The Rise of Skywalker and Black Widow from Disney, Disney would only allow it if they also play Spies in Disguise and Underwater at terms and with placement that would guarantee profit (multiple, high capacity screens).

Circuit dealing is slightly more complicated as it deals with a deal between a studio and an exhibitor where a studio will reach favorable terms with one or more exhibitor over everyone else. The best way of looking at this practice now would be if Universal reached an agreement to play the new Fast and Furious movie with Regal and AMC (who agree to pay higher terms in exchange) and only Regal and AMC.

To be clear, these protections were in place for one reason – to foster competition. Back in a time when there were far fewer theaters and most of those theaters were single-screen, access to high demand content was critical for survival. This is referenced directly in the DOJ’s review:

Most metropolitan areas today have more than one movie theatre. The first-run movie palaces of the 1930s and 40s that had one screen and showed one movie at a time, today have been replaced by multiplex theatres that have multiple screens showing movies from many different distributors at the same time.

The DOJ also referred to the fact that movies can be exploited and generate revenue on many different revenue streams. Especially now, with the large increase in broadcast revenue from Netflix and other SVOD platforms, movies are not dependent on just theatrical revenue. Let’s read from the review again:

Finally, consumers today are no longer limited to watching motion pictures in theatres. New technology has created many different distribution and viewing platforms that did not exist when the decrees were entered into. After an initial theatre run, today’s consumers can view motion pictures on cable and broadcast television, DVDs, and over the Internet through streaming services.

The basic reasoning here is: because there are so many theaters now, with so many screens, and these movies have so many more ways to make money, these protections no longer apply. Competition can be fostered without these rules. Is that right? Can we look at some data? Let’s look both at what kinds of movies are successful at the box office, and how theaters are playing them.

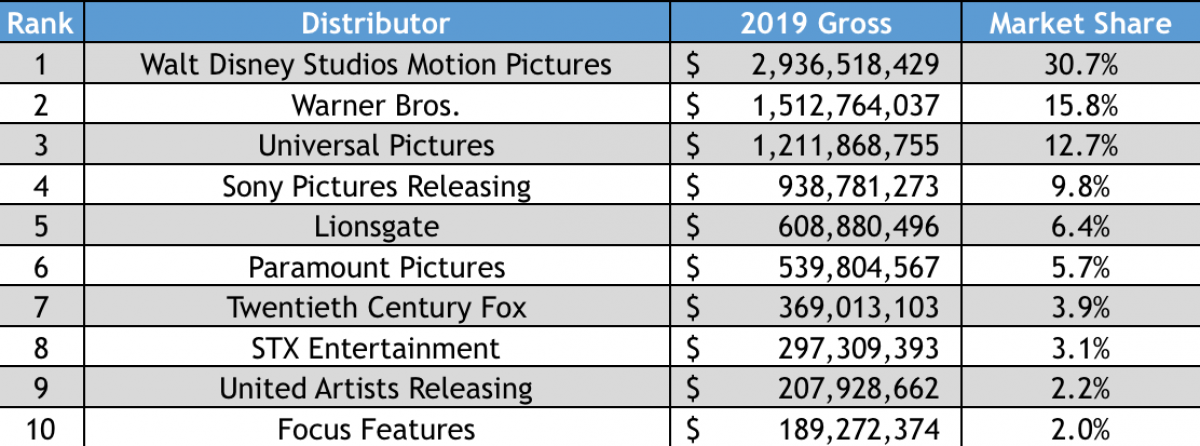

Looking at 2019 domestic box office revenue to date, let’s look at the MPA Studios (and STX and Lionsgate) compared to everyone else:

91.1% of the product that makes money is from the five majors (and their sub-labels like Focus) and STX and Lionsgate.

Let’s see what that looks like by studio:

I think we get the idea here – the exhibition space is dominated by the major studios. But what does this look like at the title level? Well, the top one hundred films of the year (Avengers: Endgame ($858.4m) to Missing Link ($16.7m)) account for $8.9b of the total $9.6 new release gross so far. The exhibition space is again dominated by the few.

To summarize, we’ve learned:

- 91.1% of the revenue comes from studio product

- 93.6% of the revenue comes from the top one hundred titles

So, from an antitrust/competition perspective, how does that product play through theaters? Let’s look. I pulled over a 52-week time period the number of films the top theatrical circuits played. Keep in mind that besides first-run titles (which Boxofficemojo (RIP) says 786 titles have been released in 2019), theaters also played event programming (like concerts, opera, and one-off theatrical events) and repertory programming (film outside their initial exploitation, usually two years or older). What we’re looking for is a way to see how diverse a chain’s programming is. Over a 52-week time period, the higher the number of films a chain plays by theater indicates how diverse their programming is. Simply, the higher their diversity index, the more films they play. This could mean that all their theaters play a lot of titles or some of their theaters play literally everything. What we’re trying to establish is, by and large, the biggest chains don’t have a wide variety of content and the data bears that out:

We can see the big three – AMC, Regal and Cinemark - have the lowest index. It’s safe to assume they are basically playing the same movies, and given that we know 90%+ of the revenue comes from the top one hundred films and these are almost all films from the studios (and STX or Lionsgate) we can now assume they are mostly playing studio content.

This is where the DOJ is wrong. The DOJ assumes that since we have so many theaters now and these theaters have so many screens, they are competing with different kinds of product. As we can see, that is not the case. The biggest chains are competing with everything EXCEPT content. A main factor the smaller chains use for competition is their diversity of content, and the DOJ is making it harder for that type of content to have a chance.

Why do I believe this? Because the chains don’t want diverse content. They will be less affected by both block booking and circuit dealing than the smaller chains, and the companies that provide the diverse content are smaller, more arthouse-oriented companies like A24, NEON, Bleecker Street, Magnolia, IFC, etc. They are already playing tons of studio content. So for them, it’s a question of which studio content to play, and I think we all know who wins there. But if the smaller chains are being forced to play more studio content on more screens, that’s less content for the arthouse exhibition and distribution companies.

But the DOJ thinks that’s okay. Why? Because movies make money on lots of different revenue streams so maybe these companies don’t need theaters. That’s only partially true, as a lot of distribution companies are not dependent on theatrical anymore. In fact, when something like Mandy makes $1m at the box office, it’s almost by accident as Mandy’s distributor will largely four-wall their releases only to secure higher pricing and placement on digital platforms. However, there are several companies – A24, NEON, Bleecker – who have built their models using the same basic template the studios have – that theatrical and theatrical revenue is the main driver for all other revenue streams. In fact, their deals are contingent on box office meaning the more box a title does, the more license fee they will receive. They will be the ones that have the most to lose.

If they die, so what? They only make up 10% or less off the pie. Free market should rule in a fair capitalist society, right? Well, allow me to argue that the long-term health of the entertainment industry is somewhat dependent on companies like NEON and A24 that are finding audiences in the 25-44 demo. Here’s my argument: on one hand, you have the studios who have gotten so good at giving the movie-going public what they want, they have put all their eggs in the franchise IP basket. We have gotten so top-heavy with what works theatrically. Marvel, DC, Star Wars, Harry Potter, Fast and Furious, Toy Story, Incredibles, Transformers, Star Trek, Spider-Man, Avatar (maybe) – this is what people want to see and the studios are giving it to them as much as possible. However, most of these franchises are in decline. Even Star Wars, at one time the crowning jewel of movies, has been damaged and showing diminishing returns. The only sure thing these days is Marvel, but we cannot expect them to sustain their success forever.

I believe the more top-heavy we get, the more opportunity open ups in the middle. I don’t believe that space can be occupied by the “mid-major” model. We can only look at the failure of companies like Overture, Relativity, TWC, Open Road, the ever-looming specter of bankruptcy for STX, and the failure of Lionsgate to sustain success beyond the Twilight and Hunger Games franchises to understand that model doesn’t work. There’s a reason the studios are out of that space. It will require more consolidation in both exhibition and the distribution business, so on the other hand, you have the successful arthouse distribution companies (and to an extent, Blumhouse as a production company) that can fill that middle space. I believe movies geared at 25-44-year-olds is the best way to fill that middle. Looking at the success of NEON, A24, Bleecker, and even the Blumhouse model, coupled with the success of the revitalized Focus Features or Disney’s Fox Searchlight, there is more room for smart, high-quality films that are for 25-44-year-olds. If the DOJ makes that space harder to fill, it will help diminish the overall business which is betting everything that audiences will continue to adore superhero movies and come back to their franchise IPs.

It’s worth pointing out that the DOJ stated that the Paramount Decrees are still under review (for two years). They say they will continue to review prohibited behaviors to ensure fair competition. They do expect everyone to “adjust to any licensing proposals that seek to change the theatre-by-theatre and film-by-film licensing structure currently mandated by the decrees” but will continue to monitor. Finally, the termination of the Paramount Decrees will have to occur in court.

NATO has been in communication with the DOJ since August over this and can be disputed in court if needed. However, the very fact that the DOJ is signaling they will look to terminate the Paramount Decrees, the consistent support the DOJ has given lobbyists and corporate interest, and my general distrust of Trump’s DOJ (and honestly NATO), I am unfortunately pessimistic about this outcome. I think it's going to be hard to close this door now that the DOJ has opened it unless new leadership can be inserted. Something for those of us who vote to consider next November.

A lot of the dialogue around this has been around studios owning theaters, but why would they? Block booking and circuit dealing mean they can force product into theaters at the most beneficial terms and placement possible. Why buy theaters when even the MPA has called the exhibition business in the US “mature”? They know consolidation is likely. Now they don’t have to. Now they can do everything they would do if they owned the theaters and they don’t have to spend the money it would take to buy the biggest chains.

You don’t have to be as pessimistic as I am. After all, my argument is based on protecting less than 10% of the business. What I have tried to do is explain what will likely happen to that 10% and how that can affect the overall exhibition business that is already dealing with a shift in consumer behavior from transactional to subscription and from exhibition and DVD to broadcast. I actually hate being Chicken Little, but the news from the DOJ is just too alarming for me not to be concerned.

As always, I appreciate your time and look forward to your comments and conversation.