How Optimus Prime’s Death Defined A Generation

It’s the end of July, and the biggest season for movies in the year. This summer, Hollywood has already given us another Iron Man movie, a new Superman, and big ass robots fighting huge effing monsters. Pretty much everything on screen this month has had at least one explosion, and all of these movies have been carefully developed by studio suits utilizing market research and test audience focus groups, with the ultimate goal being to make a big spectacle that can be understood and enjoyed by a wide enough audience so it can clean up at the box office all over the world.

And so of course this is also the season when there are dozens of articles bemoaning the state of cinema today.

Earlier this summer, Steven Soderbergh launched the first big attack on the studio system of the season when he gave an address at the San Francisco International Film Festival and drew a line in the sand between “cinema” and “movies”:

The simplest way that I can describe it is that a movie is something you see, and cinema is something that’s made…. Cinema is a specificity of vision. It’s an approach in which everything matters. It’s the polar opposite of generic or arbitrary and the result is as unique as a signature or a fingerprint. It isn’t made by a committee, and it isn’t made by a company, and it isn’t made by the audience. It means that if this filmmaker didn’t do it, it either wouldn’t exist at all, or it wouldn’t exist in anything like this form.

Next there was a big piece in the New York Times about Worldwide Motion Picture Group and how the studios are hiring them to use statistical analysis of screenplays to determine if a movie is likely to be a box office hit before they even give it the final green light. Here’s one of my favorite bits from that: “Bowling scenes tend to pop up in films that fizzle, Mr. Bruzzese, 39, continued. Therefore it is statistically unwise to include one in your script.”

Screenwriters of course complained that this kind of pseudo-science is removing the art from writing, and one of our own writers, the amazing Film Crit Hulk, totally eviscerated that article and the company they were profiling with an incredibly thoughtful analysis of how the storytelling process should work.

And all of those critiques are true.

And making movies for the widest possible audience of course means that there’s the potential for a certain amount of dumbing down of the stories that are being told.

But who cares? Because sometimes you aren’t in the mood for “cinema,” and sometimes movies made for the crassest reasons, movies made by a committee and movies made to appeal to the lowest common denominator possible can become touchstones for a generation.

After all, in his State of Cinema speech even Soderbergh admitted that a lot of the films he would classify as “cinema” are unwatchable pieces of crap. His point was that as long as those unwatchable pieces of crap are true to one author’s vision than at least we have something artistic, and there’s a voice that’s worth listening to. But I would disagree. I don’t want to listen to every voice that shouts in the wind just because it has a unique vision of lunacy.

And the flip side of that Soderbergh coin is true as well, because while there are several big budget Hollywood movies filled with explosions that are unwatchable collections of boring set piece after boring set piece, punctuated with unemotional scenes of terrible comic relief, there are also tons of examples of movies that were made to suit the calculations of the most unscrupulous bean counters who were just trying to make a buck that still became the defining moments in the cinematic lives of the audience they were made for.

Case in point? The original Transformers: The Movie (the animated version from 1986) and the Death of Optimus Prime.

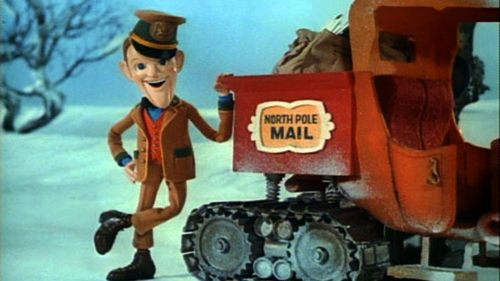

See, in the early ‘80s Hasbro acquired the rights to a bunch of Japanese toys that were both robots and vehicles. By following a set of instructions you could “transform” them from one to the other, and that was pretty cool. But it also wasn’t enough to suck you into an entire world or make you buy toy after toy after toy, so Hasbro borrowed a page out of the playbook Mattel had written a few years earlier with their Masters of the Universe line of toys and they decided to pay to produce an animated TV show that would take these shells and turn them into characters.

Optimus Prime was a semi-truck who led the Autobots, a group of car/robots who wanted to successfully blend in with human society so they could go back to their home world one day and live in peace, or something like that. Megatron was a robot who somehow turned into a tiny gun and led the Decepticons, a bunch of bad guys who wanted to shoot different colored lasers than the Autobots at whatever they could. Every afternoon on TV they had adventures, they fought each other, they introduced new characters, and they made kids around the world want to buy more toys.

After two years of that cartoon on the small screen, Hasbro helped produce a full length feature film, Transformers: The Movie, which promised an epic space battle for the future of Cybertron, the Transformers’ home world. This movie introduced us to a lot of new characters, and could have been a great way of selling more toys while still being a very standard kids adventure movie (albeit one with a great soundtrack).

But in the middle of the movie, just after a fist-bumping rendition of “The Touch” by Stan Bush, Optimus Prime and Megatron meet up for a battle, and (27 year old spoiler alert) Optimus Prime dies.

“Ha ha ha!” the kids laughed to themselves. “This is a great trick he’s playing. Good job, Optimus. Now wake up and kick his butt!”

But Optimus Prime doesn’t wake up. Optimus Prime stays dead.

And so kids in the theater start crying. Not sobbing, like we all do at the beginning of Up, but slowly, with tears running down their cheeks and a little quiver in their bottom lip. For many, this was the first father figure they’d ever had to face losing.

Years later, in college, while sipping beers at a local tavern and dealing with the loss of an actual friend, or parent, or grandparent, some of those now-grown kids could be overheard saying, “The first death that really affected me in my life was Optimus Prime. Then later my dog died, too.”

Does that sound ridiculous to you? Then GROW A HEART!!! OPTIMUS PRIME WAS A HERO!!

Sorry. It still gets to me sometimes.

So here I am, 27 years later, still thinking about a cartoon character who fell down and didn’t get back up again (at least not until 1988, when he was resurrected with the “powermaster” technology).

But what motivated screenwriter Ron Friedman to give us this pivotal moment in cinema history? The greed of the suits at Hasbro, of course.

Because Optimus Prime was popular, but maybe he was too popular. Maybe if you loved Optimus Prime and you had an Optimus Prime toy and a Bumblebee toy and maybe a couple of Decepticons for them to fight then you didn’t NEED to add a Hot Rod to your collection. But if Hot Rod became the leader? Well, you want to play with the leader of the Autobots, don’t ya kid?

There was no noble desire to express anything about the human condition and how fragile our lives are as we cling to this spinning sphere that’s hurtling through space. But that lesson was learned anyway, because OPTIMUS, NOOOO!

So there’s no doubt that for children of a certain generation Transformers: The Movie is both a fantastic piece of entertainment and a seminal moment in our lives. But according to the Soderberghs of the world, that isn’t enough to make it “cinema.”

And that kind of argument is an old one, but one that still bothers me.

I think if a movie, or a TV show, or a book or play or song speaks to you, and teaches you, and changes your perspective of the world and lets you grow as a person, then that movie is Good. Even if it’s made by a bunch of assholes sitting around a table in a boardroom, munching on cigars and looking for more money to afford fuel for their private jets to take them to Cuba so they can restock their supply of illegal smokes. It doesn’t matter, and trying to differentiate between two different stories and determining which one is “art” is a foolish endeavor.

Ultimately, nothing can be art because of how it is created. Until it enters the mind of someone in the audience, a story or a painting or a song or a movie is just a series of words, or colors, or a melody, or images flashing on a screen. But when something that we create out of nothing, based solely on the power of our minds, enters the mind of someone else in the audience? That’s where the connections are made, and that’s when at the very least that creation has the opportunity to become art.

So yes, OF COURSE let’s seek out the brave independents, and let’s support the next Shane Carruth who is even now toiling in his garage making the surprise hit of Sundance 2017. Let’s embrace the cinematic outliers and join Film Societies and respect the Masters of Cinema and cherish every opportunity we have to enjoy the classics on a big screen in a darkened theater filled with other true film fans.

But let’s not make all of that mean that we’re afraid to open our hearts and minds to the next superhero movie that’s filled with explosions that are designed with the express purpose of selling tickets overseas.

And just because we’re smart enough to know when something is “paying homage” by ripping off Kurosawa doesn’t mean we have to stop ourselves from enjoying The Wolverine, or classify the pleasure we get from it as “guilty.”

This summer, let’s bury the hatchet and let all Film Fans and Cinephiles and Movie Lovers come together and just enjoy it all. Because who knows? If you have a couple of beers in your system you might even get into the right frame of mind to find the art in Grown Ups 2. After all, maybe this is the one where they kill Adam Sandler.

This was originally published in the "Beasts vs. Bots" issue of Birth.Movies.Death. in honor of Guillermo del Toro's Pacific Rim, in Alamo Drafthouse theaters now.